Hi everyone,

Post-send note: In the original post the audio was only 1-second long. That has been fixed now.

As mentioned in yesterday’s email, I will now begin including an audio version of these essays. The audio is created in my voice with an AI. For those who listen please provide feedback on the quality and whether it is worth continuing.

Between Meta’s stock collapse and Musk’s takeover of Twitter, the future of social platforms dominated headlines last week.

On that note, today’s essay looks at VR/AR and Meta’s new headset.

—Edward

Real Fidelity

In January 2020 — before most North Americans had heard of COVID-19, let alone started processing its impact — I wrote a Marketing BS essay that connected the science of music technology (CD vs vinyl vs live concerts) to videoconferencing and office productivity. Specifically, I coined the term “real fidelity” to explain why our enjoyment of an experience — music or sports or work or anything, really — is significantly shaped by our perception of its “realness.”

Eight months later — with many people using technology to connect with colleagues, classes, and friends — I wrote a follow-up post that expanded upon the idea:

The term fidelity refers to the formats we use to communicate sounds, images, or experiences. Fidelity plays a fundamental role in the effectiveness of a marketing strategy. For instance, video can deliver a message more effectively than audio. And a video played on a large, high-definition screen is more impactful than one played on a small, low-quality screen. The most powerful fidelity is real life. A live presentation in an auditorium (usually) holds people’s interest better than a YouTube video of the event — a phenomenon that many parents discovered [in 2020], while watching children struggle with Zoom-style classes.

In that second essay about real fidelity, I used the concept to explain why companies like Netflix, Meta (then Facebook), Google, and Amazon were betting on a post-pandemic return to the office. The reason? Co-workers felt like something was missing from their collaborations. Despite the improvements in technology, videoconferencing didn’t feel as “real” as face-to-face interactions.

Humans crave that sense of “realness” — so much so that it drives many of our decisions. As I wrote in my first essay about real fidelity:

At times, our compulsion to attend live events seems to defy logic. I would never pull up YouTube and watch an hour-long lecture, but I was drawn to go see Bill Clinton during one of his “live in conversation” tours. For an $80 ticket, I sat at the back of an enormous theater, with a view far worse than the one I could have watched on my laptop.

That is the power of real fidelity.

Better Fidelity

On October 11, Meta announced that their new virtual reality headset, called “Quest Pro,” would ship by the end of the month — at a cost of $1500. Unlike their earlier Quest headsets (cost ~$400), the new device is aimed at the enterprise market. The Pro model offers multiple technical upgrades that support AR (augmented reality), like higher resolution, wider peripheral vision, automatic eye tracking, and the ability to see full color in both the virtual and physical environments. Plus, the device’s improved processors allow people to engage in more seamlessly immersive (and therefore “more real”) business meetings, brainstorming sessions, and more.

Most pundits from the mainstream media, as well as many of the smart analysts I respect (Ben Thompson, Benedict Evans, John Gruber, Kevin Roose, John Carmack, etc.) reacted to the Quest Pro announcement with skepticism. There seems to be a critical consensus about two key points:

Meta is too early: Useful VR is still ten years away — especially the social aspects. Plus, there are limited barriers to entry; when VR tech finally matures, another company can just come along and leapfrog Meta.

Customers don’t want full immersion: Meta believes that VR is the future for both office productivity and personal recreation. This strategic bet assumes that immersiveness is a defining characteristic in the tech continuum from desktop computers to laptops to mobile devices to VR. But smartphones are actually LESS IMMERSIVE than desktop computers. The shift from desktops to laptops — followed by the mobile revolution — was the result of consumer demand for convenience, not immersion. Where’s the evidence that customers are clamoring for VR experiences?

Point 1 could easily turn out to be true: Meta might be too early for VR, just like many mobile-focused companies in the mid-90s were too early.

For Point 2, though, we still don’t know how consumers will feel about immersive tech (it’s hard for any of us to have a strong opinion until developers refine the VR gear and platforms). Instead of focusing on immersion, then, I might suggest an alternative way to frame Point 2: “convenience is the most important element for bringing a new product to scale.” Getting someone to try something new is HARD — just ask P&G about the challenges with teaching people to use fabric softener. As such, I agree with critics who think Meta faces an uphill battle convincing consumers to make “putting on a headset” part of their everyday routine — especially at a cost of $1500. (The early research isn’t encouraging. Only 28% of current VR set owners use their devices daily.)

And yet…

VR has a “killer app” — presence. And, as I wrote in my first real fidelity essay almost three years ago, presence really matters. There are many types of experiences that work much better (or only work at all) when humans are physically together in the same space.

By definition, VR cannot achieve 100% real fidelity, but the technology is definitely approaching interactions that “feel” real. Nothing on a two-dimensional screen comes close. Could VR attain a level of sophistication that replicates the feeling of collective presence? Meta seems to think so.

And if VR does, in fact, ever manage to offer a reasonable facsimile for physical presence, here are some likely applications for VR (in order of “corporate-ness”):

Meetings

Conferences

Sales

Learning

Comedy

“Hanging out”

Tabletop gaming

I’m probably overlooking some other important use cases, but that list of seven is a good place to start discussions about how things might play out in VR.

Meetings

Clearly, Meta understands that workplace meetings will be a core piece of their VR business.

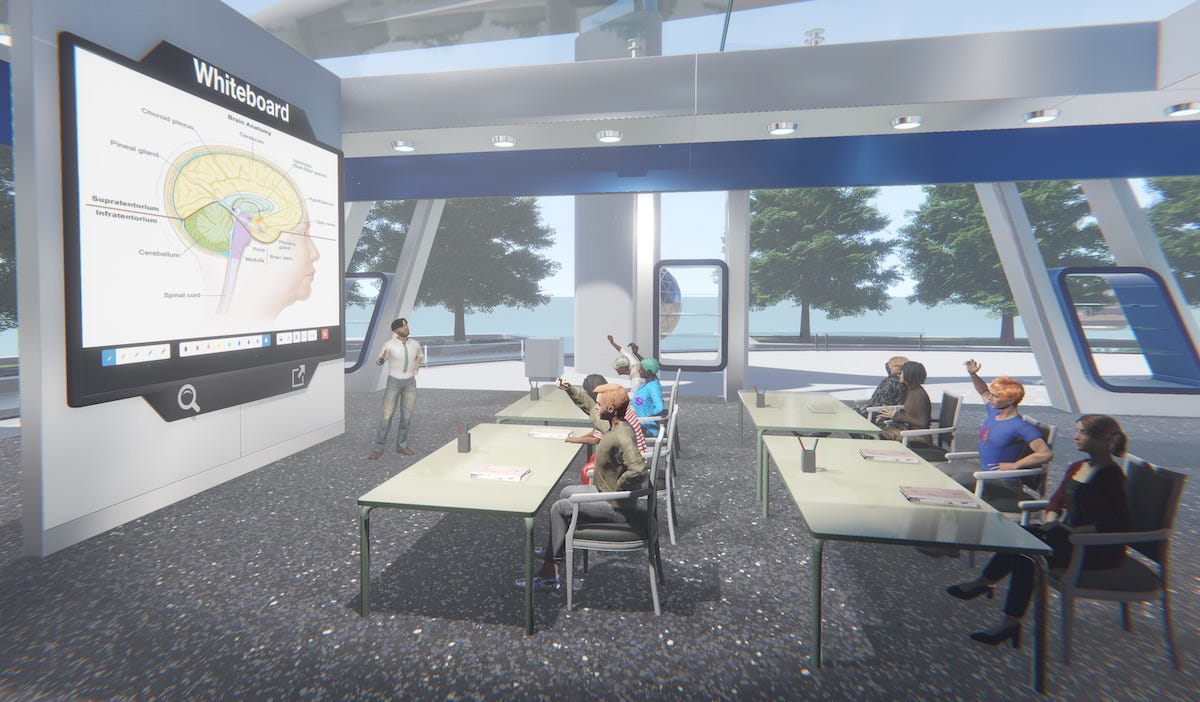

The company has already launched Horizon Workrooms — “a virtual space that brings teams together in the metaverse.” There is a web app version of Workrooms that anyone can use on their computer, just like a regular video call. But to access the VR features, you need a (base model) Quest headset. And with a Quest Pro, you can unlock AR functionality, which allows you to build a virtual model of your physical office; that way, you can interact with other people’s avatars in your familiar office environment (with the same placement of your monitors, keyboards, etc.). With Workrooms, you can also bring your computer into the space, so you don’t have to give up multi-tasking in big meetings (or if you want to pull up a slide or a spreadsheet, you don’t need to leave “the room”). You can collaborate with colleagues on whiteboards. You can throw around ideas.

Plus, Quest Pro can replicate elements of human communication. If you smile in real life, your avatar smiles. If you look away, your avatar looks away. If you put up four fingers to drive home a point, so does your avatar.

Workrooms is more than just a novelty — Meta is developing a business tool that evokes the “presence effect” of collaboration. If you have not tried a headset yet, I highly recommend it, if only for 15 minutes: The experience really does feel like you are “there” — as long as you can get over the cartoon-like graphics. It is nothing like the rows of video screens you experience on Zoom or other video platforms.

Moreover, the virtual space offers some advantages over real life (beyond the obvious convenience of working in different parts of the world regardless of time or distance). In addition to Workrooms, there are third-party software programs that allow you to build and manipulate three-dimensional designs, create and shape chemical molecules, and generate housing and infrastructure projects. Given that most people haven’t even put on a modern VR headset, it’s incredible how many high-quality third-party applications are being developed — and most are free or very inexpensive.

Last week, I was working with some clients; they are debating whether to remain a remote-first company or to establish a physical office. They see the benefits of building a company culture with in-person collaboration, but they also recognize the challenges (real estate costs, recruiting talent, and office distractions). I suggested they pause their decision — until they purchase three Quest Pro headsets ($4500) and experiment with some team meetings in Horizon Workrooms. When I receive their feedback, I will report back.

Ultimately, I expect virtual meetings will be THE feature that eventually convinces users to adopt Meta (or whatever company leapfrogs them). For the rest of today’s essay, I’ll describe how other activities might develop viable use cases for this nascent technology.

Conferences

Let’s be clear: no one decides to attend a conference because of the keynote speakers (no matter how prestigious they might be). The profile of the speakers is a way to signal the conference’s quality, so that potential attendees know the event (and its networking opportunities) will be worth their time.

For many people, the value of a conference comes down to these things:

Sales

Account management (i.e., meeting with existing clients all in one place)

Job search (subsidized by your company)

Vacation (subsidized by your company)

Love (or sex, for the cynical — subsidized by your company)

Serendipity (The most productive time I ever spent at any conference was sharing a taxi back to the airport with a random stranger who eventually became a lifelong friend)

As everyone realized over the last few years, online conferences can’t really accomplish any of those things. In turn, many people have opted to give up on online conferences altogether.

But what if you could attend a virtual conference experience that still managed to check off several of the above points? A virtual event won’t get you a vacation, but there might be ways that new tech innovations could provide suitable alternatives for the other conference goals (with a big asterisk on point 5…).

Sales

Part of the reason salespeople travel to the client is signaling. They are showing you just how much they care. Taking a client to dinner or lunch or a live sporting event can be a great way to build relationships. Duplicating those experiences in a virtual space might not be possible. But there are also millions of sales calls that have been enhanced by moving from the telephone to Zoom. And I expect that shifting those Zoom meetings into the virtual space will enhance things one step further — with a more interactive way to get to know each other, to understand the client’s business, to identify pain points and solutions, etc.

The hard part will be getting the client to put on the headset.

To reduce that hesitation, here’s an idea: for big enterprise sales with a very high potential contract value, what if you sent the CMO (or CFO or CEO) a Quest headset, along with an invitation for a meeting in virtual space? That approach is obviously expensive, but so is any tactic that tries to interrupt the workflow of a senior executive. If the take rate for the meeting is high enough, a $1500 (or even $400) headset might deliver a better ROI than sending another branded paperweight.

Learning

There’s a cringeworthy Meta ad that shows students visiting Ancient Rome and watching debates with Mark Antony. The problem isn’t the lack of possibility — exploring virtual 3D worlds is possible now, and the fidelity will only increase over time. The issue is Meta’s misunderstanding about how people learn history. Watching an experience in VR isn’t much better than watching a documentary on those old rickety TV/VCR carts (while your teacher sits at their desk, grading papers). We also know that sitting down to watch a lecture — either on a Zoom screen or in a physical classroom — is a pretty terrible way to learn anything.

There aren’t currently any large-scale education platforms for VR, but there are signs that learning may be another killer app. Motive is a Canadian tech company that’s been creating immersive video games since 2008. They’ve partnered with companies in the mining industry to develop VR-based safety training modules. In the computer simulation, workers move through an interactive mining environment that requires them to recognize hazards and operate machinery. Sitting at a computer station is obviously much safer than conventional workplace orientation methods, but what are the results like? Early studies suggest that learner retention is significantly higher than other modalities. In another example, the University of Maryland ran a test/control study of AR training versus desktop training — they found 90%+ higher retention with the AR approach.

I believe the two most important training use cases are situations where training in “real fidelity” is either very expensive, very dangerous or both. Even if VR is not as good as training on site, if it can reduce the time required working with expensive equipment (i.e., in a mine), or save lives (i.e., allow a junior surgeon to practice without the risk to a real human being), then it seems like mass adoption for those situations is not unreasonable.

Consumer-aimed educational products are also emerging. PianoVision is a VR tool to help people learn to play piano. You can imagine how effectively the right software could help someone develop muscle memory for a stationary task like that. I expect similar possibilities for activities like golf or table tennis. (In fact, there’s already a free table tennis app where you can play against another user or a “perfect AI” that feels shockingly like the real thing — without the dirty work of picking up the ball when you drop it).

Comedy

Comedy is much funnier when you are in a social setting. (This phenomenon might explain why comedies are on a downswing in Hollywood — fewer and fewer people are seeing movies in theaters, compared to solo viewing at home).

During the COVID era, there was a rise of online comedy shows. Many of the shows resembled Zoom videocalls, while others had comedians standing on stage, performing in front of a wall of screens (like this one). Many of the shows experienced tech hitches and logistic limitations — the same types of issues that companies discovered when they shifted meetings online.

For comedy, getting the right mix of audio is particularly tricky. Muting the audience makes the show feel dead, but turning on everyone’s mics to allow laughter can overpower the comedian (especially if they have to compete with random babies and dogs).

Improvements to VR could make an online comedy show feel like a social situation, with the “presence” of other people laughing around you. There would definitely be market demand for live comedy shows that people could watch from the comfort of their home.

The industry would quickly change. Stand-up comedians spend a lot of their life on the road (which is a lonely experience for many of them). With a more immersive tech platform, comics could put on a headset at 7:00 pm, deliver their 40-minute set, and take the headset off — and already be home to tuck their kids into bed or spend the night with their partner.

For producers, the cost to book a higher-profile comedian would decrease (no need to book large venues, etc.); as such, stars would have more opportunities to reach audiences around the world. Bookings might be harder to come by for emerging comedians, who would now be competing in a global market (which isn’t that different from the story of the last 20 years, as technology has reduced friction in everything).

The biggest technical challenge here is supporting large groups of people simultaneously in the same space. Right now the cap for the number of people who can be live in a single venue is only 20. That makes for a pretty poor live comedy show.

Hanging Out

VR platforms offer lots of ways for people to connect socially. Internet chat forums evolved into social media platforms; the next iteration might include having people’s avatars interact in a virtual space. Groups of friends could “gather” to watch a football game or awards show on TV — with everyone in their own individual houses. You can’t really go on a (physical) walk with someone, but you could play games like mini-golf together.

The business opportunity in “hanging out” might not be immediately obvious, but a lot of value in companies comes from lunchtime conversations, post-work drinks, bowling nights, etc.

Remote employees miss out on those types of social connections and outings. Company off-sites and retreats can help bring everyone together, but those events, by definition, will happen infrequently. VR could provide alternative ways to build a close-knit team.

Tabletop Gaming

Demeo is a VR game that allows friends to play a Dungeons & Dragons-type adventure together — controlling characters, solving puzzles, and defeating monsters. When you play, you can opt for a view that looks like a digital version of an in-person roleplaying game (people sitting around a board, moving pieces, and rolling dice). But the VR functionality also allows you to change your relative size and position, so you can zoom in and become part of the action.

Many tabletop games have already been ported into electronic form (I’ve seen families playing Carcassonne on their tablets, online chess is growing dramatically, and anyone who owned a Windows device in the 1990s knows the rules to Solitaire).

Imagine a VR environment with virtual dice, cards, and tables. People could gather and play countless games, without the need to program any “rules.” Of course, this would require players who know the rules, but no more so than playing a game in real life – only now you can do it with someone on the other side of the continent. And if you did want to learn the rules for a new game, current VR headsets aren’t good enough to let you read text from a book, but linking to a computer is an easy way to bring in written material from outside the virtual setting.

Will Meta even be around to see this?

On October 27, Meta announced their latest earnings (or lack thereof). In response, their stock quickly dropped 28%. The company is now worth $266 billion, down from over a trillion dollars last September (just before announcing the rebrand to Meta). They have fallen a long way. If they continue along this trend, will there even be a company to realize their vision of the Metaverse?

One thing VR-believers have going for them is that Mark Zuckerberg has maintained control over the business. While he only owns 14.6% of Facebook stock, his “founder shares” give him 58% of the voting rights. There is nothing stopping him from continuing to spend $10 billion per year on VR and AR R&D. While Facebook’s net earnings and cash flow have dropped dramatically from 2021 (when they were bringing in $10 billion or more of both per quarter), they still made $4.6 billion in net revenue and almost $200 million in positive free cash flow in Q3 2022. If the company ever found themselves in serious trouble, Zuckerberg could just reduce VR investments by a billion or more dollars to keep the company liquid. Meta is in no danger of folding.

The real risk to Meta is holding onto their talent. Employee compensation at Meta is a roughly 50/50 mix of cash and stock options. When the stock price drops by 70%, that means a 35% pay cut for everyone who works there. If you are smart and talented, why not leave to build products somewhere where you will be better rewarded? The silver lining right now is that there are hiring freezes at most of the big tech companies these people would consider jumping to. But that situation won’t last forever; sooner or later, Meta is going to have to address compensation. And beyond compensation, Meta will need to ensure that a very large workforce (now almost 72,000 employees), still believes in the company, their mission, and their chances of success. Zuckerberg may be a true believer in VR, but how do the marginal employees feel?

If Zuckerberg can somehow keep his employees happy and engaged, then there is nothing stopping him from going all-in on virtual reality. As a clue, here’s what one of Zuckerberg’s friends and former professors wrote about the CEO back in 2012 (in response to a Quora question about Zuckerberg’s attitude to money):

Mark's main motivations were pretty clearly based around materially changing the world and building technology that was used by everyone on the planet. It's not like he didn't know that if he was successful, he'd become incredibly wealthy - and I wouldn't go as far to say that he would've done everything he's done if there wasn't a big financial payout from it all. But that always seemed like a happy side-effect of his true goals. My impression back then was that if he had to choose, he'd rather be the most important/influential person in the world rather than the richest. And I think that's visible in how he directed the company to focus on user growth and product impact rather than revenue or business considerations. Even today, while Facebook makes a ton of money, it could probably make magnitudes more if that were its primary goal.

The post continues to explain that Zuckerberg was happy living in a small apartment and sleeping on a mattress on the floor, before his security team dragged him into a more protective environment.

It’s entirely possible that Zuckerberg is not focused on maximizing shareholder value of Meta in either the short or the long term. It’s possible, even likely, that he is spinning the story enough so that he has the flexibility to spend Meta’s billions of free cash flow towards building what he sees as the future.

If effective VR is only possible by spending $10 billion per year with a negative ROI, then without Meta’s investment it might not otherwise happen — or only far into the future when the related costs have been reduced by tangential technologies. Zuckerberg may be okay with that. He owns the wealth to make that investment. But, since his company is public and employs tens of thousands of people, even if he believed that, he could not say it. Zuckerberg has to build the narrative that the investment will eventually pay off (and that shareholders and employees are smart to invest their time and dollars with him).

It remains to be seen if Meta will be the one to make VR happen, if VR will go into another long winter, or if Meta will kick things off before another company takes it over the finish line. But it sure looks like Zuckerberg is ready to either swing for the fences or go down swinging.

Keep it simple,

Edward

Edward Nevraumont is a Senior Advisor with Warburg Pincus. The former CMO of General Assembly and A Place for Mom, Edward previously worked at Expedia and McKinsey & Company. For more information, check out Marketing BS.

Share this post