Amazon, Apple, Google, and Sort Order

Welcome to Marketing BS, where I share a weekly article dismantling a little piece of the Marketing-Industrial Complex — and sometimes I offer simple ideas that actually work.

If you enjoy this article, I invite you to subscribe to Marketing BS — the weekly newsletters feature bonus content, including follow-ups from the previous week, commentary on topical marketing news, and information about unlisted career opportunities.

Thanks for reading and keep it simple,

Edward Nevraumont

Amazon and Sort Order

Last week’s newsletter (“The NFL and Scarcity”) introduced the idea of “sort order” — the process of deciding which items appear at the top of a search list. A recent article in The Wall Street Journal — based on anonymous interviews with Amazon employees — claimed that the company is manipulating the order in which products are listed:

Amazon.com Inc. has adjusted its product-search system to more prominently feature listings that are more profitable for the company, said people who worked on the project — a move, contested internally, that could favor Amazon's own brands. … Amazon optimized the secret algorithm that ranks listings so that instead of showing customers mainly the most-relevant and best-selling listings when they search — as it had for more than a decade — the site also gives a boost to items that are more profitable for the company. [Emphasis mine]

The WSJ article describes the tensions between Amazon’s retail executives and the “A9 team” that oversees the company’s search algorithm. As both the operator of the dominant online marketplace AND the seller of its own private-label (Amazon Basics) products, the company could obviously benefit from algorithms that emphasize profitability (never mind concerns about anticompetitive behavior). Not surprisingly, Amazon has flatly rejected the implication they are influencing the methods by which products are ranked.

Amazon’s denial about changing “search results to include profitability” appears to contradict some of their other recent statements. In the WSJ article, Amazon spokespeople admitted that profitability is, in fact, one of the drivers of sort order. Furthermore, Amazon expressed a sense of confusion that the members of their algorithm team believed the company’s strategy was changing:

Amazon said it has for many years considered long-term profitability and DOES look at the impact of it when deploying an algorithm. “We have not changed the criteria we use to rank search results to include profitability,” said Amazon spokeswoman Angie Newman in an emailed statement.

Amazon declined to say why A9 engineers considered the profitability emphasis to be a significant change to the algorithm. [Emphasis mine]

Let’s ponder the ethics of the situation.

What do you think: when an online marketplace develops a sort order algorithm, would the evaluation of profitability result in some kind of ethical violation?

Personally, I don’t think that considering the impact of profitability is a transgression of ethical business practices. Imagine this hypothetical situation: a company demanded payment from Amazon before allowing their products to appear on Amazon’s online marketplace. In that scenario, would Amazon be ethically obligated to sell the product?

Obviously not!

So, why SHOULDN’T Amazon assess profitability when deciding which products to sell? And if profitability is an acceptable factor for choosing products to sell, shouldn’t it also be an acceptable factor for deciding which products to place at the top of their search results? Ignoring profitability seems like an example of corporate incompetence, rather than ethical enlightenment. Every retailer on the planet considers profitability when deciding not only which items to carry, but also where to place them within stores. Amazon (obviously) stocks several orders of magnitude more inventory than any brick-and-mortar retailer, but Amazon still needs to decide which of those millions of products to show customers on any given search.

In short, I think that Amazon should absolutely consider profitability.

That said, Amazon should not ONLY consider profitability.

Winning with Loss Leaders

Most North American consumers, even those with limited financial knowledge, understand the concept of a “loss leader” — a product sold below market cost in order to stimulate the sales of additional (more profitable) goods or services. (Historical side note: the phrase, “There’s no such thing as a free lunch” originated from taverns in the 19th century, when owners offered free food in order to attract drinking customers. Patrons who showed up for the free lunch without buying any drinks were regularly thrown out onto the street. Modern-day loss leaders use a little more psychology and a little less violence).

When we talk about loss leaders, we usually refer to retail industries, most notably grocery stores. That said, we’re increasingly seeing examples in the digital space. Amazon definitely sells some products at a short-term loss, and I would not be surprised if many of those items appear near the top of their search results (for all the same reasons that conventional loss leaders exist).

Amazon has always demonstrated a “long-term greedy” mindset. Like Walmart before them, Amazon uses aggressive prices to constantly remind customers that they offer great value. I launched my career in Canada — back when Amazon only sold books. As an avid reader, I would open three web browsers to compare prices between Amazon, Chapters, and Indigo (the “Barnes & Noble” and “Borders” of Canada). After several purchases, I realized that — even with discounts at Chapters or Indigo — Amazon usually offered the lowest price. Eventually, I stopped wasting my time on price comparisons and went straight to Amazon whenever I wanted new books.

Quite likely, Amazon could have generated greater profits by being a little less aggressive on price. But think of the benefits of giving up some short-term profits — more than a decade later, I am now a consumer that spends upwards of $10,000 a year on Amazon. A focus on being “long-term greedy” has paid off for Amazon.

Let’s return to the accusations that Amazon is manipulating the order in which products are listed. In Amazon’s tweet, they state, “We feature products customers want.” Apart from denying the influence of profitability, Amazon has never provided specific details about which factors DO impact their sort order algorithms. I expect the algorithm considers some of the following elements:

price competitiveness

weighted clickthrough rate

click-to-purchase rate

key word relevance

brands you have purchased before

manufacturers you have purchased before

reviews and ratings

frequency of branded searches vs. others in the category

variety (i.e., different price points within the top ten results)

dozens of other factors

In the big picture, those factors probably bear close resemblance to the ones used by Google when deciding which ads to place at the top of their search results. And the ones used by Expedia to decide which hotels to list at the top of their search results. And the ones used by Facebook to decide which posts to show at the top of your newsfeed results. And the ones used by Apple to decide which apps to place at the top of your App Store search results.

Plus, the elements considered by Amazon’s algorithms are probably similar to the type of factors used by Walmart in deciding which products to feature in their endcap displays.

Digital Endcaps

For a product, appearing on Amazon is the 21st-century equivalent of securing shelf space in a national retailer. If we continue this analogy, placing your product at the top of Amazon’s search results is the 21st-century version of displaying your product on the endcap at a local retailer.

In traditional retail, there were two ways to obtain an endcap display:

Offer a product so appealing that the retailer wants to feature it (as a means to drive sales and to improve the customer experience).

Pay the retailer to receive the prominent placement.

Over time, the largest retailers moved away from #1 and started demanding #2 — that way, they could extract more money from (more profitable) manufacturers.

At the end of the day, though, the money all came from the same place. As we all know, manufacturers sell products to retailers at a price that includes a markup on their costs; retailers then sell those products to consumers at a price that includes their own markup. What happens if retailers charge manufacturers for the “privilege” of placing their products on the shelf (called “slotting fees” in industry parlance)? In that case, manufacturers face a couple of options to maintain their margins:

Pay the slotting fees out of their profits.

Raise the prices they charge the retailers (to cover the slotting fees).

For a manufacturer, option #2 is obviously preferable (in most circumstances). Let’s think about this situation: retailers charge a slotting fee to the manufacturer, causing the manufacturer to increase its price for the retailer.

Wouldn’t it be more efficient for the manufacturer to just sell the product to retailers at lower prices? That way, the retailers can make more margin, providing an incentive to feature the products on their endcaps — not because of slotting fees, but because prominently placing a (now higher-margin) product would increase sales and profits.

So…are slotting fees and endcaps just smoke and mirrors?

Sometimes.

During my career at P&G — almost two decades ago — our policy forbid the payment of slotting fees. In practice, though, things were more complicated. Every “Account Manager” (their name for a salesperson) controlled a modest “Business Development Fund” (BDF) budget, to spend with retailers at their own discretion. Account Managers regularly used the BDF to place advertisements in newspaper flyers or to secure endcaps in retail locations.

Alternatively, for a retailer like Walmart, Account Managers could simply take the entire BDF and apply it as a discount on the everyday price. With this plan, the Account Manager reaches a simple agreement with Walmart to do reasonable in-store promotions based on the specific product — without any money changing hands.

For P&G, the money actually DID all come from the same place. How much was smoke and mirrors depended on the degree of trust between the Account Manager and their retail partner. If the retailer and the manufacturer both operated rationally, then things like slotting fees or payments for flyer ads were just distractions from running the business in the most efficient way.

Paying for Position

With the emergence of online sales, an opportunity existed to abandon inefficient retail tactics like slotting fees. E-commerce demonstrated the benefits of an economic system where every party behaved rationally. Amazon, in particular, exemplified this idea with the management of their sort order, which placed the “best” products at the top (with “best” as a combination of customer satisfaction, sales results, brand reputation, etc.). With a “rational” sort order (i.e., not rigged in Amazon’s favor), the company was leaving money on the table. Around 2012, Amazon introduced “sponsored listings”: companies could suddenly PAY to place their product at the top of the sort order. Sponsored listings are essentially digital endcaps — no different than what Walmart, Kroger, and Sears were doing forty years ago.

How important is placement at or near the top of a list? VERY important. As I wrote in last week’s newsletter:

In 2012, London hosted the Olympic Games. For the first time in Olympic history, all events were available for online viewing, free of charge. People from around the globe watched the livestreams to cheer on athletes and teams.

Can you guess which sport received the highest number of visits?

Not gymnastics, the perennial Olympic favorite. Not swimming, either. The sport that received the most online visits was…archery. I’m guessing you’re surprised by this answer. Apologies to Robin Hood and Katniss Everdeen, but archery isn’t exactly the most “popular” sport.

Why would archery receive more clicks than any other sport? One simple reason: the website listed the events in alphabetical order. And “Archery” appeared at the top of the listings.

When people search online, they regularly select whatever item appears on top.

SmartInsights (an online learning platform for marketers) has studied the impact of Google clickthrough rates by position.

The chart provides some clear conclusions. The link in the first position receives just under 30% of the clicks. There’s quite a drop-off for the links in second (14%) and third (10%) position. The remaining links — combined — receive less than 50% of the clicks. As they say, “if you’re not first, you’re last.”

SmartInsights analyzed data from Google, but I’m confident the conclusions hold true for other websites as well. For example, the vast majority of Expedia’s hotel bookings go to providers that hold the first position in their respective categories.

Sitting at the top of digital search results is FAR more valuable than securing an endcap display in traditional retail.

So…how do things end up on top of a list?

Some organizations don’t employ algorithms to determine sort order. Instead, they use a simple method like alphabetical order — which results in archery (or their “archery”-level products) receiving the highest number of clicks. For most digital lists, though, things end up on top for one of two reasons:

Organic

Paid

Everyone understands the basic principle of paid searches: whoever pays the most money grabs the position at the top of the list. (The actual execution of paid search is a little more complex. Google uses something called “quality score” to ensure that paid listings consider not only the price that companies are willing to pay, but also the relevance of the ad for search users).

Organic searches, on the other hand, people perceive as “pure” — based upon a meritocracy of quality and relevance.

In practice, though, what’s “best” for the user is not always obvious. For instance, suppose a user searches for a hotel in Amsterdam — a travel site should just show them a list of hotels for that city, right? But which Amsterdam hotels are “best,” and for which users?

At Expedia, a team of smart people tested many different algorithms, trying to optimize the experience for the users. Over time, the team managed to increase conversion rates by showing users the “right” hotel for them, based on customer reviews, location, historical conversion rate, and other factors.

The ability to develop algorithms that boosted conversion was heralded as a team success, BUT…it was also academic. Although the conversion rate improvements were measurable, the impact was relatively small. In fact, the results narrowly outperformed test pages that listed the hotels randomly.

Time and again, users simply booked whichever hotel appeared at the top of their search results. When Expedia realized this fact, they stopped focusing on algorithms, and started emphasizing sort order. Market managers (who worked with the hotels), leveraged this tool to extract concessions from hotels: “If your hotel wants to be on top of the sort order this week, I need you to give me 2 more points of margin” or “I know you can sell your whole inventory during Mardi Gras, but I expect you to hold a few rooms for us” or “I want Expedia guests to receive rooms with a view of something other than that dumpster.”

Strictly speaking, Expedia was not using profit margin to sort hotels, but they were still leveraging their power to get what they needed from suppliers.

Self-serving Searching

Google’s motto is famous — “don’t be evil.” To that end, Google has tried to maintain organizational “firewalls” between the activities of their paid and organic search teams. In recent years, though, even Google appears to have been swayed by opportunities for profit.

Rand Fishkin, founder and former CEO of Moz, posted his thoughts about patterns in Google search results. (I highly recommend reading the entire piece, released in August 2019).

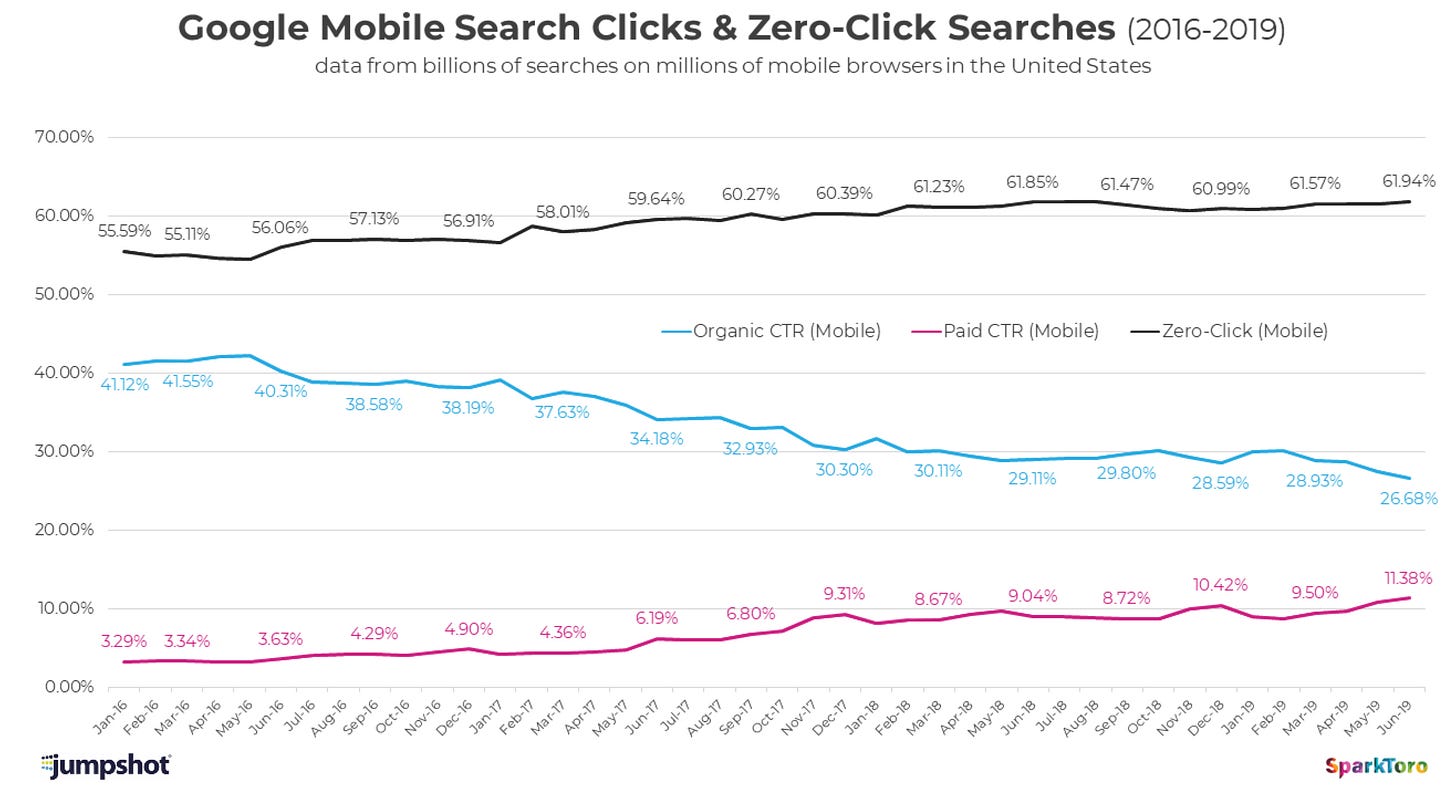

Fishkin’s article includes a particularly compelling chart (drawn from Jumpshot) that illustrates types of Google search clicks on mobile devices.

You can easily spot the trends: from January 2016 to June 2019, the percentage of organic clickthrough rates dropped steadily, while paid clickthrough rates almost quadrupled. There was also a relatively small growth of “zero-click” searches (a category that spans a range of outcomes: (1) users who aborted a search, (2) users who found the answer in the search results without clicking any links, (3) vocal searches via Alexa, etc., and (4) many other issues).

Although Google’s algorithms operate with a cloak of secrecy, one fact is clear: Google IS increasingly steering traffic from organic clicks to paid clicks.

I am fascinated by the reactions to this information. For years, tech culture has condemned the idea of manipulating organic results for anything but “pure” reasons. And yet, experts and watchdogs seem fine with the idea of Google shifting search clicks from organic to paid.

The Google plot further thickens, because the company seems to be finding success within organic search, even as organic clickthrough rates decline.

Check out this chart from Fishkin’s article:

In Q2 2019, around 12% of organic clicks went to Google-owned websites. (Organic non-Google clicks are 42.42%. Organic Google clicks are 5.98%. Therefore, the total of organic clicks is 48.4% and Google’s share of organic clicks is 12.35% (5.98/48.4))

Does Google’s share of organic clicks seem high to you? That figure seems unnaturally high to me. Google would probably justify this information by explaining that Google-owned websites are awesome and the right place to send people, but…I’m still skeptical.

Of course, Google is not alone in stacking the deck to their own benefit.

On September 9, 2019 — one week before the WSJ accused Amazon of manipulating sort order to increase profit — The New York Times published an article exposing Apple’s preferential treatment of their own products at the top of their App Store search results:

Apple’s apps have ranked first recently for at least 700 search terms in the store, according to a New York Times analysis of six years of search results compiled by Sensor Tower, an app analytics firm. Some searches produced as many as 14 Apple apps before showing results from rivals, the analysis showed.

In one blatant example, a February 2018 search for “music” resulted in Apple-owned apps holding the first SIX results. Spotify — perhaps the best-known music streaming platform — was relegated to the eighth spot on the list. Did you even know that Apple had six music-related apps? (In case you’re curious: Apple Music, GarageBand, Music Memos, iTunes Remote, Logic Remote, and iTunes Store).

When challenged by reporters, the Apple senior vice-presidents in charge of the App Store denied any nefarious conduct:

Apple’s [executives] … said there was nothing underhanded about the algorithm the company had built to display search results in the store. The executives said the company did not manually alter search results to benefit itself. Instead, they said, Apple apps generally rank higher than competitors because of their popularity and because their generic names are often a close match to broad search terms.

“Nothing underhanded”? Music Memos — an app for recording music on your iPhone — ranked higher than Spotify, the first music streaming service to reach 100 million paid subscribers.

Despite the clear skewing of search results in Apple’s favor, I actually believe the SVPs’ claim that sort order was not manually altered. Never chalk up to villainy what can be explained by incompetence.

So…what’s going on with Apple’s sort order?

No one has ever accused Apple of designing an effective search engine. If I wanted to find, let’s say, a flashlight app, I would never start with the App Store. Instead, I would go to Google and search for “best iOS flashlight apps.” After scanning an article that reviews flashlight apps, I would visit the App Store and try to find the best-reviewed app — a process that usually requires sifting through branded search and copycat apps with similar logos, etc. Bottom lines: (1) the App Store is a mess, and (2) search is not nearly as easy as it looks.

The NYT’s piece states that Apple uses 42 “signals” to determine placement in the App Store. Only five signals are identified:

# ratings and rating average

relevance to search (keyword)

# of downloads

# of clicks

if you already have an app from that publisher on your phone

All of those signals seem very reasonable, at least in isolation. Generally speaking, wouldn’t you prefer an app with a high rating versus one with a low rating? Or an app that was relevant to your search, especially if it was downloaded by high numbers of people? Plus, if you previously downloaded an app from a specific publisher, wouldn’t that bolster your confidence in downloading another app from that publisher?

Quite likely, the App Store team genuinely tried to create an algorithm that returned super relevant results to their users. The design, however, overlooked the fact that some signals favored Apple’s own apps. Consider this one: “if you already have an app from that publisher on your phone.” As any iPhone owner can attest, the device comes preloaded with multiple Apple apps. Thus, when iPhone users search the App Store for the first few times, the algorithm heavily weighs the signal about publisher. That headstart pushes those apps near the top of the sort order, and once an app appears near the top, it receives more clicks from other iPhone users. The cycle continues…

In terms of algorithm design, a company CAN correct for this scenario (by evaluating clicks weighted by position). In my experience, though, not even Google uses this method to fully compensate for the advantages of high-ranking positions. And if Google can’t master the concept, there’s no way Apple has developed an effective system.

Sort Order Meets Human Nature

Without question, positions near the top of search results are extremely valuable. They also invite closer scrutiny. Companies that control sort orders usually attempt to show the “best” results — and not just out of kindness (or fear of government regulation). By providing quality results, companies earn the loyalty of their users; after securing user loyalty, companies can then mix the “best” results with paid ads. In simplest terms: a better search system will attract a greater number of customers, which will allow the company to charge higher ad prices.

As such, marketplaces are usually incentivized to show the most relevant results. So how do we end up with situations like 12% of Google searches showing Google-owned websites, Music Memos ranking higher than Spotify, and Amazon’s “choice” being their own private-label brands?

I can think of a few reasons. First, there are many times when the best result IS a Google-owned website (or an Amazon Basic, or an Apple App). The second explanation is straightforward: the algorithm design team screwed up. But the most important reason, I believe, stems from the realities of corporate culture and human nature.

For instance, we know that Google searches appear to favor Google-owned websites. Keep in mind that members of the sort order team are humans — they share the same cafeteria with employees on other teams, they repeat the same corporate slogans, etc. Perhaps Google’s sort order team really, truly believes that the other teams at their company are developing exceptional products. Or…maybe the sort order teams’ evaluation of other departments’ work is clouded by the positive social impressions of their colleagues. Perhaps a product team received company-wide recognition for something. If the sort order team didn’t rank that (award-winning!) project highly enough, then…it might be a sign that the sort tool is not as effective as they believed.

That’s human nature, not algorithmic meddling.

Final Thoughts

These tech companies are massive. No one person — not even the senior vice-president of the App Store — controls the sort order. Instead, there is a team (or more likely, multiple teams) of people, all trying to do the best at their particular job for their particular division. When Expedia owned TripAdvisor, we desperately wanted to be listed at the top of their sort order. Sometimes we were — but ONLY when we negotiated to pay that division more than our competitors would pay. TripAdvisor knew that we would look bad if we weren’t on the top on our own company’s site, so they were known to play harder with us than with Priceline and Booking. Think of how often you receive faster responses from an external vendor than from an internal department.

Manipulating operations to drive a company’s self-interest is tricky, even when that interest is communicated directly and consistently by the CEO. A conspiracy to manipulate sort orders AGAINST the public intentions of a particular group — for the benefit of a different division — is far beyond the ability of any of the (large) corporations where I’ve worked.

Conspiracies are hard. And achieving hard things is rare.

Keep it simple,

Edward

If you enjoyed this post, I encourage you to click the little heart icon below my bio. Thanks!

Edward Nevraumont is a Senior Advisor with Warburg Pincus. The former CMO of General Assembly and A Place for Mom, Edward previously worked at Expedia and McKinsey & Company. For more information, including details about his latest book, check out Marketing BS.