Marketing BS: CCG and the Upside of Legibility

Good morning everyone,

Legibility is a BIG topic. Today’s essay is the first installment of a three-part series on the importance and impact of legibility.

Given that a new baby is on its way any day now, I expect that parts two and three will be released after a bit of a pause. Thanks for your patience.

—Edward

Collectibles and Commodification

On July 1, Blackstone — one of the world’s leading investment firms — announced they had purchased a majority stake in CCG (Certified Collectables Group). The deal values CCG at more than $500 million. Blackstone’s press release provides some more context:

CCG is a leading, global provider of expert, impartial and tech-enabled services that add value and liquidity to collectibles. Founded in 1987, CCG offers authentication, grading and conservation services that have unlocked billions of dollars in secondary market value… Mark Salzberg, Founder of CCG, said, “When I established CCG, I had a vision that we would transform collectibles into an asset class that is trusted by collectors, dealers and investors around the world.”

What does it mean to “transform collectibles into an asset class”? Today’s essay looks at the concepts of “legibility” and commodification.

Blackstone clearly believes in CCG’s ability to “unlock billions of dollars.” In a nutshell, CCG has developed systems to quantifiably assess the condition and value of collectible items — like coins, sports cards, and comic books.

Suppose you were lucky enough to own a copy of Amazing Fantasy #15 (the 1962 comic book with the first appearance of Spider-Man). If you wanted to sell your copy — without CCG — you could refer to the Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide (now in its 51st edition). The Price Guide not only lists the estimated value for comic books, but also provides information to assess the physical “condition” of each issue on its grading scale: mint, near mint, very fine, fine, very good, good, fair, or poor. For example, a Near Mint copy should be almost perfect; “Acceptable minor defects on a NM copy include: a very small amount of spine stresses, very minor instances of denting (two or three at most), slight corner blunting, and minor (less than 1/8") bends without color breaks.”

As you can imagine, evaluating the physical grade of a comic book is a subjective process. Especially because individual sellers have an incentive to over-grade their issues, just like perspective buyers would want to argue for a lower grade. (Note that the Overstreet Guide lists the “suggested” value for comics — people still need to be willing to sell or buy at those prices. When I collected comics in the 1980s, there were always healthy (or not so healthy) debates about what a comic was “really worth.”)

CCG has completely changed that way that comics are valued. Instead of subjective disputes about whether a bent page should downgrade a comic book from Near Mint to Very Fine condition, CCG introduced an “objective” system of evaluation. Comic book owners can submit their issues to a professional third-party grader who will provide a definitive numerical score (from 0.5 to 9.8). The CCG grader then seals the comic book in a hard plastic case (referred to as a “slab”) that prominently displays its grade.

Even if you’re not a comic book fan, you can easily spot the difference in quality between these three copies of Amazing Fantasy #15:

After a comic book is sealed in a CCG plastic case, the comic’s value is transformed from qualitative to quantitative. No longer a piece of art with subjective value, the item is now a commodity.

FYI, here are the most recent sales prices for the above issues of Amazing Fantasy #15:

Grade 2.0 — $22,000

Grade 6.5 — $125,000

Grade 9.4 — $1.35 million!

If you have a comic book collection in soft plastic bags, you can only estimate — with very rough accuracy — its total value. On the other hand, if you own comic books in CCG slabs, then you can update your valuation (by using recent transactions) within a few percentage points.

CCG has converted comic books from art into stocks. The increased certainty about market-tested valuations has increased collectors’ confidence to make certain investments. And as the value of (some) comics became clearer, their value has massively increased.

Legibility

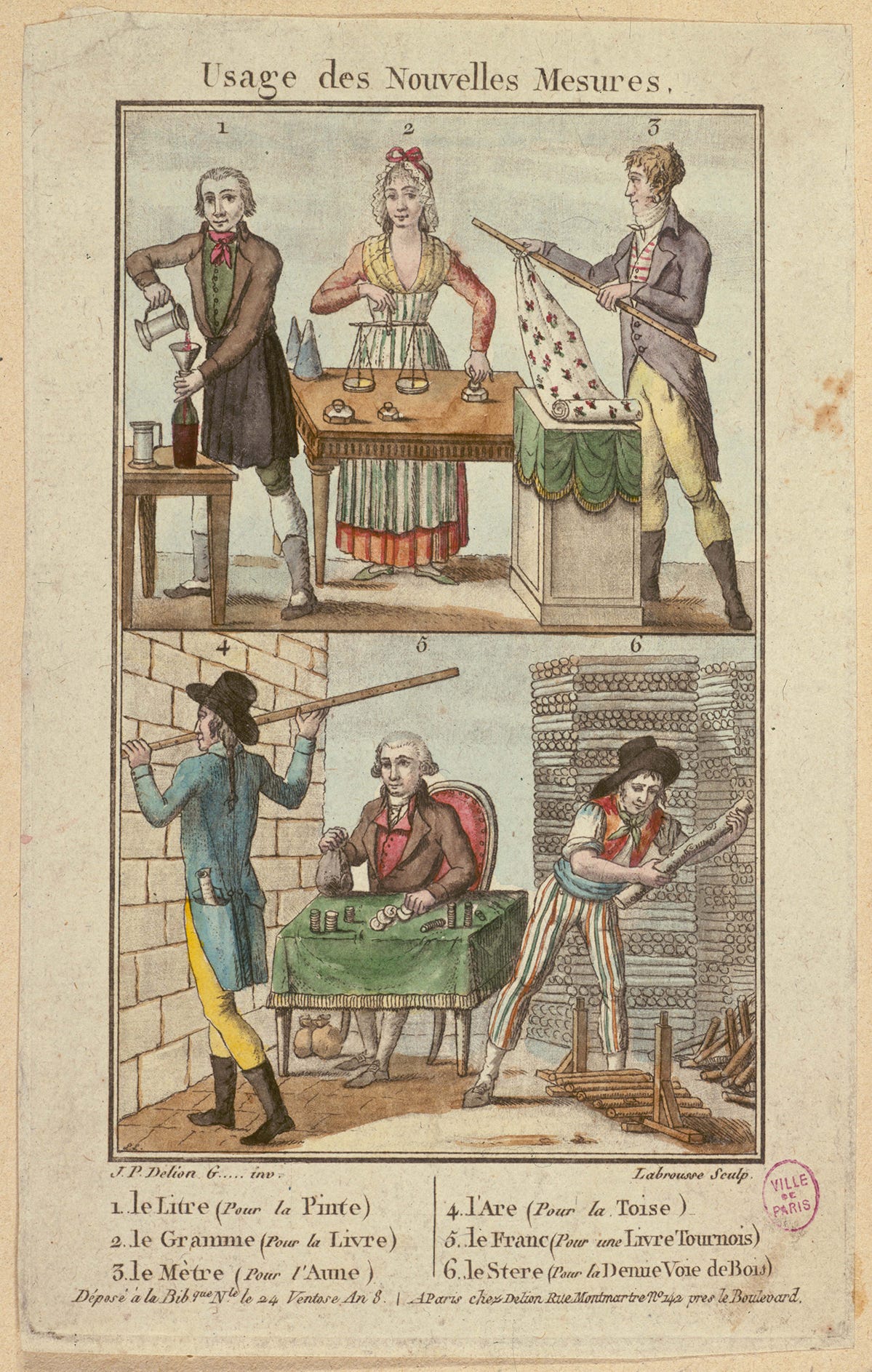

Yale professor James Scott wrote several books about comparative politics and agrarian societies. In 1998’s Seeing Like a State, Scott highlights the wide variability of measures and standards that existed across different regions and time periods. For example, in 18th-century France, the size of a pint of grain varied from 0.93L to 3.33L, depending on the municipality. In addition to the lack of standardization, there were even questions about the measurement process:

How the grain was to be poured (from shoulder height, which packed it somewhat, or from waist height?), how damp it could be, whether the container could be shaken down, and finally, if and how it was to be leveled off when full were subjects of long and bitter controversy.

Scott uses the term “legibility” to describe the ways that governments tried to organize and monitor society — like, for instance, standardizing the size of a pint of grain. But rather than a spirit of societal cohesion, legibility was driven by economics and politics. If you were a king, taxing grain was a much easier process with standardized weights and measures.

Scott argues that the forced mandating of legibility was responsible for significant amounts of civil unrest. In a future essay, I will dig deeper into James Scott’s perspectives about the downsides of legibility. Today, I want to focus on the ways that legibility can create real value. CCG’s impact on the comic book industry is one example. And there are many other ways that transforming a process from qualitative to quantitative can generate positive results.

Tipping

When I was in high school, everyone could easily recognize the “cool kids” (I wasn’t one of them…). But what would happen if you polled every student to create a ranked list of the “top 20 coolest kids” in the school? Almost certainly, you’d have disagreements. And suppose you wanted to know which school in the entire city had the absolute “coolest” kids — it’s nearly impossible to imagine an effective method of comparison.

Moreover, what does “being cool” even mean? Opinions about high school coolness vary as widely as the size of a pint of grain in 18th-century France.

Author Malcolm Gladwell rocketed to fame by trying to understand the ideas of coolness and popularity. In his iconic 2000 book, The Tipping Point, he defined three types of people that were necessary for a product or idea to become popular:

Mavens: The “experts” who possess specialized expertise or knowledge of a particular category (e.g., the guy you went to for computer-buying advice in the 1990s). Mavens know what really matters in the category, and they are happy to share.

Connectors: They know everyone — especially people across social circles.

The Salesmen: The persuasive, charismatic people who use their “soft” influence to push ideas and products.

Ever since The Tipping Point was released, business leaders have been searching for ways to standardize the “Tipping Point Process.” Executives hoping to make their brands “go viral” tried getting the right people to push their products at the right time. (I’m not aware of a single company that’s been consistently successful with this strategy; if you can think of any examples, I would love to hear about them).

In the first few years after the book’s launch, there was an emergence of agencies that tried to recruit potential mavens, connectors, and salespeople. On the advice of these agencies, companies distributed free products to potential influencers. (I once received a free pair of Johnston & Murphy dress shoes. I might not be a footwear maven, but I still wear that brand today when social norms require me to wear something other than Allbirds or Sauconys).

In practice, these agencies struggled to systematically identify mavens, connectors, and salesmen. Many consumers were fortunate to receive free products — without providing any real value to the brands. But some REAL connectors/maven/salesmen did, in fact, exist —and they helped drive the popularity of brands.

Ultimately, both groups (those who added no value and those who added lots) were all compensated the same way — with free products. The former group was vastly overpaid and the latter one significantly underpaid — all because no one could identify which people belonged to which group. You might be able to know who was cool from your high school class, but there was no way that Johnston & Murphy could recognize — at scale — who was cool enough to pay to wear their shoes.

Then along came the social media platforms. They took intangible concepts of coolness and influence and then developed tangible ways to measure impact. Social media made popularity legible.

Before social media, companies could assess the marketing value of famous celebrities (based on metrics like “box office receipts” and “album sales”). But there wasn’t any coherent method for locating the 1000 or so people who could help your fashion brand reach viral status.

Everything changed with the advent of Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube. Companies could suddenly collect quantified metrics on the influence of any individual person. Instead of relying on qualitative feelings like “this person seems like a connector,” you could review metrics such as “number of followers” or “average engagement per content created” or “clickthrough rate of promoted products.”

While I remain skeptical of the ROI on current influencer investment, there was definitely a time in the early days of social platforms when you could build a brand by paying “influencers” with large followings to promote your products. Ting Wireless is a reseller of mobile phone service. They grew their early brand by sponsoring individual content producers — before the market became saturated. Ting was one of the original sponsors of Joe Rogan’s podcast. They paid him a marginal amount more than “free product” for shoutouts on his show. Current estimates suggest that Rogan now charges $200,000 or more for a host-read ad on his show (which gets 10+ million downloads per episode).

Legibility of influencers allowed brands to quantify their value, and — in turn — empowered influencers to charge closer to the value they could generate. Legibility transformed influencing from “a way to boost personal status within a social network” into “a strategy for monetizing popularity at scale.”

Marketing Legibility

“Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is I don't know which half.”

—That famous John Wanamaker quote about advertising offers a good description of most 20th-century marketing tactics.

Advertising and marketing were mostly illegible. The best marketers were usually just the best salesmen, selling the idea that they were good at marketing — think Don Draper from Mad Men. Companies could easily track when sales increased, but it was very difficult to ascertain whether the increased sales were driven by the marketing and advertising, or by some other extraneous variable. Even when companies could verify that the marketing WAS responsible for the boost in sales, it was impossible to know which part of the marketing did the heavily lifting. Was it the placements? Was it the targeting? Was it the creative? And if it was the creative, what — exactly — was it about the creative that worked so well?

Without legibility, the marketers who could tell the best stories about their work were often the ones who received the contract for the next big launch.

Over the last 20 years, the marketing world has been completely reshaped by the vast improvement in attribution. While it’s still easy to waste money with bad (or badly targeted) marketing, it’s getting easier and easier to connect marketing spend to the revenue generated by that spend. The largest increase in marketing dollars over the last decade has been allocated to digital marketing channels like Google and Facebook. But even Google and Facebook have been so overwhelmed with demand for their placements that advertisers have been forced to look broader for “legible” advertising opportunities. The result has been record-setting growth in the last quarter from companies like Twitter, Snap, and LinkedIn.

Legibility allows companies to directly compare the value they are creating versus the costs. The more legible something is, the lower the risk to investing. This comfort, in turn, drives up the demand, which then increases the price until it’s very close to the value created by the new legible “thing.”

Today, not ALL marketing is legible. For example, what is the value of your brand refresh? That said, all marketing — and not just digital advertising — is becoming more and more legible over time. With greater legibility, a company’s marketing department can move from being a cost center to a profit center. In late Q1 and early Q2 last year, uncertainty about the global pandemic caused many companies to cut their marketing budgets. But within marketing, the legible budgets were relatively untouched. It’s hard to spend $1 million when you don’t know if your company can survive the next 12 months, but it’s hard NOT to spend $1 million if you know that investment will drive $2 million in profitable revenue.

Legibility caused comic books to 10x in value over the last 20 years. Legibility propelled Google and Facebook into becoming the fifth and sixth most valuable public companies in the world. And legibility carved a path for CMOs to becomes CEOs.

But as James Scott make clear in Seeing Like a State, there are many downsides to legibility. I will explore those issues in part two of this three-part series. Until then…

Keep it simple,

Edward

Edward Nevraumont is a Senior Advisor with Warburg Pincus. The former CMO of General Assembly and A Place for Mom, Edward previously worked at Expedia and McKinsey & Company. For more information, including details about his latest book, check out Marketing BS.

Acknowledgements and suggested reading

I’d like to thank a few writers for inspiring many of the ideas discussed in this (and future) essays about legibility and Seeing Like a State.

Scott Alexander, Slate Star Codex

Venkatesh Rao, Ribbonfarm

Byrne Hobart, The Diff

I highly recommend checking out all three of those essays (and writers).