Corona — The Beer and Virus

Good morning everyone,

I hope you enjoyed the novelty of a Leap Day (Happy Birthday to anyone born on February 29). Media outlets are devoting more attention to coronavirus, so it seemed like a topical subject for this week’s newsletter.

— Edward

Coronavirus and Corona

Last week, the S&P 500 index was down 11% — its worst week since 2008. What caused the drop? Fears about the coronavirus (or, more accurately, COVID-19). Experts believe that COVID-19 could wreak havoc on global supply chains, decimate the tourism industry, and, oh, potentially kill 2.1% of the global population. During the stock market drop, travel companies understandably took some of the largest hits: Expedia (-13%), Carnival Cruises (-15%), and American Airlines (-27%). Of course, disasters can present enormous opportunities for some industries, and a number of companies actually saw their stock value INCREASE. For instance, Kodiak Sciences (biopharmaceuticals) was up 14%. You would expect that companies like Clorox (bleach products) will see a boost; additionally, some analysts predict positive gains for technology companies that could help people with the isolation of quarantine: Zoom (videoconferencing software), Netflix, etc.

I want to move past finance and explore a marketing-related perspective: the impact of the coronavirus on Corona beer. If the coronavirus could kill you and the people close to you, is it still okay to bring Corona beer to social events?

The word “corona” is a translation of the Spanish word for “crown.” Corona the beer uses a crown as their brand. Corona the virus, when magnified, apparently looks like a crown (although frankly I don’t see it).

To be clear, the only connections between Corona beer and coronavirus are very superficial: similar-sounding names and crown-like visual elements. Could that tenuous link be enough to harm sales of the beer brand?

Corona is owned by Constellation Brands (for US distribution) and InBev (international). Last week, Constellation’s stock price dropped 14% and InBev was down 16%. For context, other large beer manufacturers were also down, but not nearly to the same degree: Carlsberg (-6%), Molson-Coors (-9%), and Heineken (-8%). Based on those numbers, it seems like the market may be punishing the owners of Corona on the order of ~5% of their market capitalization, just for the negative associations of their name.

But as I discussed when Peloton’s 2019 holiday ad made the news, stock prices can be affected by multiple factors; this fact complicates our ability to isolate the specific impact of one specific factor. On February 27, InBev shared their (weaker than expected) results from Q4 2019, along with a forecast for a 10% decline in Q1 2020 (due to reduced demand in China). InBev is clearly facing a coronavirus problem, but not a Corona BRAND problem.

Public relations firm 5WPR conducted a survey that found “38% of beer-drinking Americans would not buy Corona under any circumstances now.” As many pundits pointed out, the survey design included some significant flaws. Most notably, 5WPR overlooked this fundamental detail: most beer-drinking American would not buy Corona under regular circumstances, never mind the health crisis. The 5WPR survey circulated around social media, including posts from mainstream news outlets like CNN International. Despite the clear misinformation, Corona’s brand took a hit.

In a more methodically sound study, market research firm YouGov assessed the impact of the coronavirus on consumer opinion of Corona beer. Their results do not offer good news for the pale lager:

Corona’s Buzz score — a net score based on whether US adults have heard anything negative or positive about the brand — decreased among those who have an opinion of the brand, from a high score of 75 at the beginning of January to 51 as of late February.… YouGov data also shows purchase Intent for the brand is at the lowest it’s been in two years, though the summer-y beverage which is closely associated with beach holidays does see substantial seasonal fluctuation. [Emphasis mine]

Constellation does not seem deterred by the negative connotations of “corona.” Case in point: a new ad campaign for their Corona Hard Seltzer featured the slogan, “Coming ashore soon.”

On social media, the reaction was overwhelmingly critical. Many people expressed astonishment about the perceived insensitivity of the brand. Why would any company poke fun at an epidemic that is already responsible for thousands of deaths? Constellation insisted they would not back down:

Our advertising with Corona is consistent with the campaign we have been running for the last 30 years and is based off strong consumer sentiment. … While we empathize with those who have been impacted by this virus and continue to monitor the situation, our consumers, by and large, understand there’s no linkage between the virus and our business.

Despite Constellation’s public determination to continue their campaigns, they appear to have caved to public pressure (or at least softened their position). When television spots for the seltzer went live last week, they did NOT contain the “coming ashore” language. Furthermore, the Twitter post that originally introduced the “coming ashore” slogan has been deleted from their feed.

What’s in a Name?

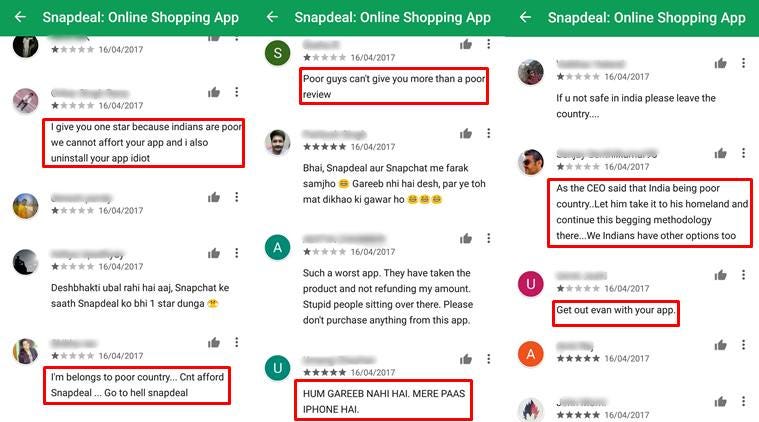

Back in 2017, Snapchat CEO Evan Spiegel was accused of boasting that the app had no plans to “expand into poor countries like India and Spain.” As you can imagine, Spiegel received significant flack for his candor.

Do you know who else faced a backlash, especially in India? Snapdeal — an India-based e-commerce company that is completely unaffiliated with Snapchat.

Confusion about the similarly named companies resulted in scathing online posts about SnapDEAL — for the comments (allegedly) made by the CEO of ShapCHAT.

You can find corporate cases of mistaken identity all over the globe. Suppose you wanted to buy stock in Ford Motor Company (~$40 billion valuation). Using an online trading platform, you might see the ticker symbol “FORD” and make your purchase. To your surprise, you would have ended up with a stake in Forward Industries (~$10 million valuation). In August 2019, CNN published a report on the phenomenon of “buying the wrong stock.”

"Most investors don't reverse the incorrect trade until a week or more," said Andrei Nikiforov, assistant professor of finance at Rutgers University-Camden. "That's how long it takes for the stock price to return to normal, probably once investors realize they made a mistake." Nifkorov wrote a research paper on the topic with fellow assistant professor Vadim Balashov. They found some investors didn't even wind up selling the stock they incorrectly bought. Instead, they just rationalized the purchase as still being a good investment.

Stock markets include a number of confusing symbols, where a small company holds the ticker name you would expect for a major corporation.

APLE is used by Apple Hospitality, a real estate investment trust — NOT the manufacturer of iPhones (AAPL).

When Twitter (TWTR) IPO-ed in 2013, a small (and recently bankrupted) electronics retailer named Tweeter (TWTRQ) saw a 1000% jump in its stock price.

After Google announced their acquisition of Nest (the smarthome innovators), the unrelated Nestor (a security tech company) spiked in price by 1800%.

In 2001, Michael Rashes published a paper (drawn from his Harvard dissertation in Economics) that analyzed investment activity for stocks that share similar names:

This paper examines the comovement of stocks with similar ticker symbols. For one such pair of firms, there is a significant correlation between returns, volume, and volatility at short frequencies. Deviations from “fundamental value” tend to be reversed with in several days, although there is some evidence that the return comovement persists for longer horizons. Arbitrageurs appear to be limited in their ability to eliminate these deviations from fundamentals.

The bottom line: name confusion is a relatively common occurrence, without any detrimental effects for most investors. That said, major companies like Apple generate a LOT of stock activity, so even a small number of errors can move the needle for Apple Hospitality (APLE).

Unique is Better than Good

When I first stepped into the CMO role at A Place for Mom, I hated the brand name. Beyond the obvious fact that we also provided services for Dads, the company’s name seemed, well, hokey. A future IPO was a possibility for APfM. Would investors want to buy a company with a name that sounded “unprofessional”? We seriously considered switching our name to “Senior Referral Services” or something equally bland. To that end, we even commissioned a brand study to research options for a new name.

In the end we kept the name, and that was the best possible outcome. While our name WAS hokey, it was also unique. No one ever confused us with anyone else. The same was not true for our competitors. Take a look at the names of some of the rival companies in our industry:

SeniorHomes.com

SeniorLiving.com

SeniorLiving.net

SeniorLivingNet.com

SeniorsForLiving.com

If people could mistake Corona beer for coronavirus, or Ford Motor Company for Forward Industries, think how easily they might confuse SeniorLiving.net with SeniorLivingNet.com.

Some non-insignificant percentage of SeniorLiving.com’s advertising spend was generating lift for their direct competitors. The more similar the brand names and the less unique the brand assets, the more advertising leakage you will experience.

When creating a brand, you need to find an easy-to-remember name that “fits” the category. But perhaps even more importantly, you need to pick a name that cannot be easily confused with your competitors’ brands.

As a name, “A Place for Mom” was unique. “Senior Referral Solutions” was not. Unique proved far more valuable than concepts like “professional” or “not hokey.” Our brand research study confirmed this fact, but we should have realized it without hiring external consultants.

Final Thoughts

People around the world are wondering how to prepare for COVID-19. At this point, there are few ways that an individual can reduce their risk for infection, besides (1) not freaking out, and (2) focusing on simple things like handwashing.

I recommend that Corona follows a similar plan: (1) don’t freak out, and (2) focus on simple actions that will grow the business in the long term. They should continue marketing their products as if the virus never existed (but maybe drop the “coming ashore” slogan…). Every business faces unexpected problems that are totally outside of their control. Sometimes you just take the punches and get back up again. COVID-19 is bad news for the Corona brand, but it is bad news for everyone.

I expect the biggest impacts on Corona’s business will not result from brand association with the virus, but rather (1) disruption to supply chains, and (2) a general decrease in consumer demand for beer, especially if people limit their social interactions. Corona’s legacy as a “vacation beer” might result in even lower sales if (when) tourism numbers plummet. Some confusion between Corona the beer and corona the virus will continue to exist, but the impact will be marginal — and frankly, there is not much that Corona can do about a pandemic. Executives at Constellation Brands and InBev should remember that the Corona brand has been around since 1925 — it has survived many difficult downturns and it will outlast the coronavirus, too.

Keep it simple,

Edward

FYI — my family created this plan for dealing with COVID-19.

If you enjoyed today’s newsletter, I encourage you to click the little heart button below the “Subscribe Now” box. Thanks!

Edward Nevraumont is a Senior Advisor with Warburg Pincus. The former CMO of General Assembly and A Place for Mom, Edward previously worked at Expedia and McKinsey & Company. For more information, including details about his latest book, check out Marketing BS.