Marketing BS: Degrees of Difficulty

Good morning,

I hope you enjoyed yesterday’s interview with Charbel Zreik, managing principal at Manifestation Capital. He shared a great story about hotels and WiFi — which led to lots of insights about fast feedback, employee equity, and more.

—Edward

Diving and Difficulty

A couple of weeks ago, Malcolm Gladwell and Adam Grant connected on Clubhouse to discuss their latest books (The Bomber Mafia and Think Again, respectively). Their conversation touched on Grant’s personal experience with competitive diving — especially the concept of “degrees of difficulty.”

Today’s essay applies degree of difficulty to other contexts and industries.

During the Olympics Games, television audiences love the diving competitions — the quick spins and turns are mesmerizing. For most of us watching at home, there’s a vague sense of what constitutes “good” dives.

The expert judges, on the other hand, evaluate each athlete’s performance on very specific technical elements:

The length of time and quality of any handstands

The height at the apex of the dive

The distance of the diver from the diving apparatus

The properly defined body position of the diver

The proper amounts of rotation and revolution

The angle of entry

The amount of splash

The judges’ scores are totalled and then multiplied by the degree of difficulty — a numerical assessment of the dive’s specific elements (ranging from 1.2–4.8). The degree of difficulty for each dive is determined by a five-part formula:

Height

Number of somersaults and twists

Positioning

Approach

Entry

For instance, suppose five judges delivered scores of 8.0, 8.0, 7.5, 7.5, and 7.0, for a total of 38 points. That score would then be multiplied by the dive’s “degree of difficulty” — say 2.3 — resulting in a final score of 38 x 2.3 = 87.4 points. (At high levels, the process is more complicated, with some scores being omitted, etc.)

Versions of degree of difficulty appear in other sports, too — figure skating, gymnastics, climbing, etc. And when I coached improv theater, it was clear that making people laugh was challenging, but improvising in song or iambic pentameter was even more difficult.

I think “degree of difficulty” can add a lot of value to evaluation metrics. And yet, the concept is rarely used outside of sports.

Look at healthcare. Hospitals and doctors are regularly rated on their success in treating patients; as one example, ProPublica runs a Surgeon Scorecard.

There is a major limitation of these scoring systems: they do not incorporate “degree of difficulty.” Imagine two hospitals, one serving a very healthy population and the other serving a less healthy population; we should expect the first hospital would score higher in terms of patient outcomes than the second one. And for a common procedure like knee replacement surgery, an active and healthy person will, on average, recover more quickly than an inactive and unhealthy patient. Scoring the competency of the orthopaedic surgeon is one thing, but surely the profile of the patients will impact the results.

Without correcting for degree of difficulty, how accurate are scores for hospitals and doctors? Taken one step further, it’s possible that current healthcare assessment tools actually incentivize hospitals and doctors to take on the easiest cases in order to boost their scores.

Back to competitive diving — what might happen if judges stopped considering degree of difficulty? The “correct” strategy for the divers would be clear: only attempt the simplest dives (and execute them as well as possible).

Determining Difficulty

So why don’t we use degree of difficulty multipliers more often?

Check out this section of the Clubhouse conversation between Adam Grant and Malcolm Gladwell:

Grant: One of my biggest frustrations with diving is that the formula for degree of difficulty is almost completely bogus. How did you decide that when someone does a front four-and-a-half that’s a 3.8 degree of difficulty on a three metre, but when they do an inward three-and-a-half it is only a 3.4. You could change that scale dramatically and we would have different Olympic Gold Medalists. We would have completely different dives done…

Gladwell: Hold on hold on hold on. This is fantastic. Are you saying there is an underappreciated degree of difficulty with the concept of degree of difficulty?

Grant: At minimum there is an underappreciated degree of difficulty in asking people who judge a sport to come up with a meaningful quantitative metric for scoring the sport.

Determining the degree of difficulty for anything is HARD.

Consider these two accomplishments:

Scaling your new business to a run rate of $100,000

Growing a $1-billion business to a valuation of $2 billion

Which one was “harder” to achieve? I suspect most of you would answer with the same response: “it depends.” Fair enough, but what — exactly — does it depend on? What are all of the factors that might impact your answer, and to what degree?

Sporting events have specific parameters about rules, duration, etc. Developing a quantitative scale for degree of difficulty is doable because sports have a limited number of variables. Most professions, however, are far more open-ended than competitive diving. With tech startups, for example, there are infinite variables for how things might unfold. As such, trying to quantify WHICH challenges are harder than other challenges is almost impossible.

This limitless variability explains why the degree of difficulty concept is rarely implemented anywhere except for a handful of sports.

But when we don’t correct for degree of difficulty, we can encourage less-than-optimal results. For many sales roles, employees are compensated based on their total sales — with no consideration for how difficult (or not) those sales were. People in sales commonly give the excuse, “I had a bad territory.” Just because the excuse is common doesn’t mean the excuse is WRONG; some territories ARE harder than other ones.

But a company’s sales quotas rarely consider “territorial difficulty.” Everyone knows which regions or customer sets offer the “lowest degree of difficulty,” and the top salespeople do everything in their power to get the easiest assignments.

Most sales managers resolve these issues without needing to create a formal “degrees of sales difficulty” metric. But that doesn’t mean the company’s practices are optimizing the talents of their salespeople.

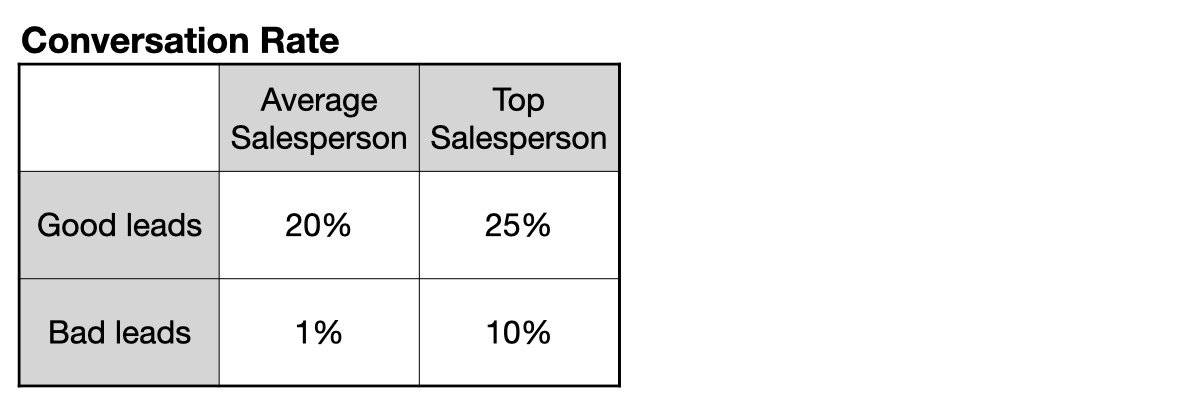

Imagine a company with 1 “average” salesperson and 1 “top” salesperson. The company just acquired 100 “good” leads and 100 “bad” ones.

Which leads should you give to each of your salespeople? The answer isn’t always obvious.

Consider this example:

In this scenario, the top salesperson is much better at converting both types of leads. They take the good leads from a 20% conversion rate to a 25% conversion rate. The bad leads, which are almost worthless for the average salesperson (1% CR) are “okay” when the top salesperson works with them (10% CR).

But the “base rate” of conversion is not as important as the “incremental conversion” of what a top salesperson can achieve over the average.

With that idea in mind, the manager for the above scenario should assign her top salesperson to the BAD leads. Why? The numbers speak for themselves.

If you follow the conventional practice of “good leads to top salespeople,” you will end up with (100 x 25%) + (100 x 1%) = 26 sales.

But if you reversed who got which set of leads, you would hit a higher number of total sales: (100 x 20%) + (100 x 10%) = 30 sales.

In the real world, of course, the top salesperson would complain that the low quality of the leads hurt their sales figures.

And here’s where the “degree of difficulty” could improve the situation. The manager could adjust for degree of difficulty by setting the commission for a bad lead at 20x the value of a good lead. All of a sudden, the top salespeople would start fighting to take the bad leads. (And the company’s sales would increase, too).

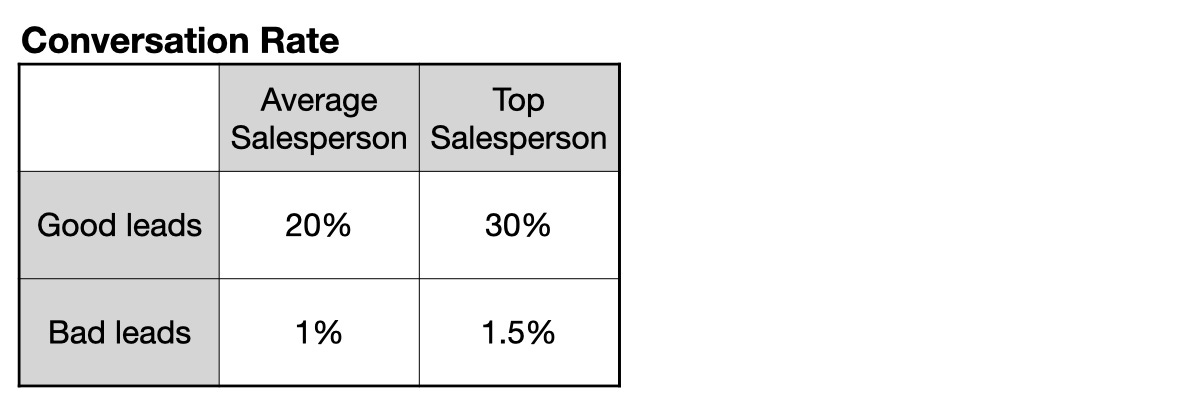

The previous example helped illustrate a point, but the discrepancy between average and top salespeople isn’t usually that vast. A regular conversation chart looks more like this:

As you can see, the top salesperson is 50% better at converting than the average salesperson — regardless of the type of lead. When this happens, the optimal strategy involves giving your best leads to your top salesperson.

(100 x 30%) + (100 x 1%) = 31 sales

(100 x 20%) + (100 x 1.5%) = 21.5 sales

In this case, there was alignment between the company’s incentive to maximize total sales and the top salesperson’s incentive to work the best leads.

Still, there’s a common real-world situation where degree of difficulty adjustments could prove useful. New salespeople are often left with bad leads; as such, they have a hard time catching up to the top salespeople.

Even if managers don’t factor degree of difficulty into their sales structure (like a 20x commission for converting bad leads), they can still consider the challenges facing the new salespeople. If the manager is AWARE of the degree of difficulty (and when it comes to bad leads, they often are), then they could consider “incremental conversion” rather than the “base rate” of conversion.

For example, when a new salesperson (who we know is working with the bad leads) starts hitting a conversion rate of 2% — more than double the expected rate for an average salesperson — the manager should consider bumping the novice up to the A-team and giving them more of the good leads.

Rookie CEOs

In a January article, the Harvard Business Review shared some surprising data:

In a study of 855 S&P 500 CEOs appointed over a 20-year period, the researchers found that those with experience in the role consistently underperformed their novice counterparts over the medium to long term. First-timers led their companies to higher market-adjusted total shareholder returns, with less volatility in the stock price. Among CEOs who headed two successive companies, 70% performed better the first time—and for more than 60%, their second companies failed to keep pace with the overall stock market.

How is it possible that first-time CEOs perform better than experienced CEOs — including their own later attempts at running companies?

HBR offers two explanations:

Experienced CEOs tend to fall back to using the same techniques they used the first time, even if those techniques are no longer useful in the new setting.

Experienced CEOs tend to be more focused with cost cutting, while rookie CEOs tend to be more focused with growth.

Those are plausible explanations, but no one becomes a CEO without any experience at all. And why wouldn’t first-time CEOs ALSO fall back on the same (no longer useful) techniques they implemented as senior executives?

Maybe the real reason has less to do with the individuals and more to do with the companies. Experienced CEOs are often hired to run very different types of companies than the ones that hire rookie CEOs.

Perhaps the experienced CEOs are given companies with higher “degrees of difficulty.”

When I interview CMOs for the Marketing BS podcast, we always discuss how they landed their first head of marketing role. How did they make the jump from running PART of marketing to running the entire thing? My guests often mention some combination of being in the right place at the right time, delivering on the role they were currently in, and leveraging the relationships they had built throughout their career.

Getting your first shot at a CMO role requires both exceptional skill and exceptional luck. But once you have experience as a CMO, you will be frequently approached for more CMO opportunities. And the types of available CMO opportunities for experienced CMOs are DIFFERENT — both in quality and quantity.

When I was looking for my first CEO role, everyone told me I would need the stars to align perfectly. Bringing on a CEO without previous CEO experience is RISKY. Boards would need to believe two things: the person was a perfect match, and the chance of failure was low.

But for a company in dire straits — that is NOT the time to bring in a rookie CEO. In the case of trouble, boards look for leaders with a successful record of turning things around.

Back to the central point of the HBR article: WHY do experienced CEOs underperform versus rookie CEOs? And why do they spend more time cutting costs and less time pushing growth?

Because the types of companies that hire rookie CEOs are not the types of companies that NEED cutbacks. Boards are only comfortable taking a chance on an unproven CEO when the risks are limited.

In some ways, this CEO phenomenon is the opposite of the salesperson problem. We usually want to give experienced salespeople the BEST leads. We leave the bad leads to the rookies who do the best they can with them. And that is fine for leads — you know 99% of those bad leads are going to be worthless anyway. A company, though, is far more valuable than a set of leads; we shouldn’t be surprised that boards are cautious about their threshold for risk. And when things are looking very bad for a company, that’s when they bring on the most experienced CEO they can afford.

The same principle holds true for CMO roles. After my first experience as a CMO — where I helped turn around a company — the types of CMO roles offered to me were generally from companies facing difficult situations.

When a CMO departs from a company where things are going well, the board is often happy to promote one of the outgoing CMO’s lieutenants. It’s only when things are going south that the board looks outward for someone else — and more experienced — to help.

In my second CMO role, we successfully navigated the company to a sale. But I was not AS successful as my first experience. And I don’t think that was because I focused too much on cutting costs or re-using old playbooks.

I will leave you with this:

Keep it simple,

Edward

Edward Nevraumont is a Senior Advisor with Warburg Pincus. The former CMO of General Assembly and A Place for Mom, Edward previously worked at Expedia and McKinsey & Company. For more information, including details about his latest book, check out Marketing BS.