Marketing BS: In praise of advertising

Good morning everyone,

Today’s essay raises the idea that advertising might actually improve the content consumption experience.

In this week’s podcasts, you will learn more about David Atchison, the CEO of Jove Software and former CMO of Zulily.

—Edward

Today’s essay is sponsored by Pulsar

Stop doing generic social listening: tap into Audience Intelligence

Different communities talk about the same topic differently.

Carry out instant conversation analysis + audience segmentation in just one tool with audience intelligence platform Pulsar: understand the public conversation, identify the top communities in your audience, and glean actionable creative & media insights to power your marketing.

The adding of ads

You might have noticed that I recently added sponsors to Marketing BS.

Some quick context: I did not go out and search for sponsors. One hundred percent of the companies came to me, asking to be featured. The money is not very significant — just enough to cover the costs of the essay editor and the podcast service.

But even without any outbound effort, working with sponsors requires additional time (approving ad copy, ensuring UTM links are operational, reporting on results, etc.).

So why bother?

We all know about wasted advertising dollars. In general, though, advertising is good for the advertiser. If advertising was NOT good for advertisers (in the aggregate), then over time advertisers would stop advertising.

For content producers, like people who write newsletters, the value of advertising is less clear. The ability for content producers to monetize their work — through advertising and/or paid subscriptions — varies depending on their product and audience.

For general interest topics (like pop culture), few consumers will purchase a subscription to read about subjects that are covered by free alternatives like TMZ, etc.

For newsletters that provide expert knowledge (like insights on company bankruptcies and restructuring), some consumers will readily pay to access exclusive content.

For content aimed at a specialized audience (like real estate agents), there are often advertisers that want to target that group. The content producers might find that it is easier to offer the content for free and then monetize through ads to that specialized group.

In many cases, the “right” answer involves a mix of both subscriptions AND ads.

For many content producers, advertising can feel like a “necessary evil.” The ads “pollute” the non-advertising content, but they also pay for the production of that non-advertising content.

And from the perspective of content consumers, advertising is usually presented as a complete negative. Being forced to view ads is the “cost” you pay in order to access the content. Instead of paying $5/month in cash to use Facebook, you pay with your attention (around $14/month if you live in America).

We are constantly told that “no one likes ads.”

But what if that commonly held truth is wrong? Could there be an argument that advertisements actually IMPROVE the content consumption experience?

That question might sound heretical, but since this is a contrarian newsletter, let’s at least consider the possibility.

Television advertising

When VCRs began gaining mass-market traction, the television networks and their advertisers were terrified. The fear was understandable. The network/advertiser relationship — the core of the American television industry — could have been destroyed if people at home decided to record their favorite shows and then fast-forward through the commercials.

But the networks and advertisers had been overly concerned. People liked television for its convenience. Recording shows was typically a back-up plan for people who weren’t able to watch live — not as a standard habit so they could fast-forward through ads.

A couple of decades later, TiVo popularized the digital video recorder that allowed people to pause and rewind live television. This innovation DID cause many people to skip ads (with good timing, you could tune into a show in progress, fast-forward through all of the commercials, and still finish by the scheduled time). Still, the TiVo-style of ad skipping was relatively insignificant in the grand scheme of the advertising channel. As Professor of Marketing Science Byron Sharpe recently tweeted, “Despite industry fears, TV ad avoidance has not increased.”

Even with new tech breakthroughs, old habits die hard. People are still exposed to a lot of “ads per unit time” spent watching network and cable television. Plus, people still spend a lot of time watching TV.

We are now moving into a third phase where more and more screen time is spent watching subscription streaming services, many of which do not show commercials (HBO Max, Netflix, Disney+). We are finally seeing a decline in time spent in front of television advertising (but it’s not dead yet!). The popularity of streaming services might suggest that consumers are looking for ad-free video entertainment. More likely, though, people are more attracted to the convenience of on-demand programming than by the appeal of ad-free viewing experiences. In other words, the convenience drives the penetration, rather than the lack of advertising.

The enjoyment of ads

If you ask people “do you enjoy television advertisements?”, almost everyone will reply “no.”

And yet, there are at least SOME ads that people seem to enjoy.

The Super Bowl is not only the big game for the NFL, but also the biggest stage for TV commercials. Each year, many people watch the spectacle primarily (or even partially) for the ads.

In Canada, television networks normally replace US commercials with Canadian ad content during all simulcast programming. But for a few years, Canadian networks sought an exemption from the policy, based on the argument that the marquee ads were an integral part of the Super Bowl programming.

Previous Marketing BS essays and briefings have mentioned Ryan Reynolds’ clever ad campaigns (like the Aviator Gin parody of the “Peloton wife” spot). The actor’s ads — which he distributes via his popular social media channels — consistently rack up millions of views. A lot of the promotional content is so entertaining that people actively try to find and watch the ads.

Clearly, though, the Super Bowl and Ryan Reynolds are the exception, rather than the rule. Those types of ads were specially created as entertainment. In contrast, most ads are entertaining only to the extent that is required to grab viewers’ attention before trying to sell a product. Very few people in the world would watch a television station that featured 100% advertising (that said, the Home Shopping Network — a station that exclusively plays long-form infomercial advertisements — continues to draw an audience).

Exceptions aside, most people clearly prefer to watch television without commercials. Plus, most consumers are willing to pay for the privilege. But some research has suggested that ad breaks can actually IMPROVE the viewing experience. Leif D. Nelson, Tom Meyvis, and Jeff Galak outlined this argument in their paper, “Enhancing the Television‐Viewing Experience through Commercial Interruptions”

Consumers prefer to watch television programs without commercials. Yet, in spite of most consumers’ extensive experience with watching television, we propose that commercial interruptions can actually improve the television‐viewing experience. Although consumers do not foresee it, their enjoyment diminishes over time. Commercial interruptions can disrupt this adaptation process and restore the intensity of consumers’ enjoyment. Six studies demonstrate that, although people preferred to avoid commercial interruptions, these interruptions actually made programs more enjoyable.

You’re probably surprised by the researchers’ conclusions: people enjoyed their television-watching experience more — significantly more — when the advertising breaks were present than when they were removed.

The authors believe the results can be attributed to the passivity of the television experience. The enjoyment of watching a TV show diminishes over time. The commercials provide the viewer with a quick interruption, which seems to “reset” people’s enjoyment of the show back to a higher level.

Or perhaps the entertainment value of the show seemed higher when contrasted with the quality of the ads?

I discovered a similar effect during my time at Expedia. In our hotel listings, we generally put the highest converting properties at the top of the sort results. When we experimented by including a low-quality hotel near the top, the overall conversion rate of the page went UP — even though no one selected the “bad” hotel. The direct comparison with a low-quality hotel made the premium properties seem even more attractive.

Paid search

In the 1990s, search engines like Yahoo filled their pages with display ads that monetized their traffic.

But when Google first launched its search engine, there were no advertisements. The ad-free strategy was a combination of both technology (the limited number of images helped their page load much, much faster) and philosophy (co-founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin wrote grad school papers that argued against advertising-centric search engines).

When Google finally decided to incorporate ads, they only allowed text listings that targeted specific keywords. Even with those conditions, Google worried that the ads would detract from the consumer experience. Eventually, though, they felt like they had no choice. Other attempts at monetization — like licencing their software to help companies build internal search, or even to competitors like Yahoo themselves — were not paying the bills. So Google reluctantly started accepting paid search ads. The rest, as they say, is history.

Google search result pages (SERPS) introduced two types of listings: paid and organic. (A third type was later added, but it’s not relevant for this discussion).

Strategies for organic listings are commonly referred to as “Search Engine Optimization”; tactics for paid listings are called “Search Engine Marketing.” Unfortunately, those terms are not very descriptive — both types of listings actually involve both optimization AND marketing. The organic results are “chosen” by Google’s algorithm, but we have witnessed the emergence of an entire industry that exists to help companies “optimize” their websites’ chances of being selected.

Over the years, Google and these optimizers engaged in a technological arms race. Google has ultimately won the battle (at least for now). Most of today’s “SEOs” now try to design sites that comply with Google’s guidelines, instead of using “Black Hat” tactics to propel their sites to prominence.

Among pages that rank highly for organic listings, there are some common attributes: fast sites, with lots of content, that have been linked to by other high-profile sites. The algorithms tend to overweight directories (Expedia and TripAdvisor will generally outrank Marriott for non-branded searches, just as Yelp will outrank Cheesecake Factory). In addition, older and higher-awareness brands enjoy significant advantages.

That last point — the preference for more established companies — offers a principled argument in favor of paid listings.

Suppose you have created a new product that you believe could revolutionize a category. As an example, let’s use the ReMarkable — a Kindle-like device that lets you take handwritten notes with the “feel” of pen and paper. (I own one and love using it when I’m not in front of my computer).

Unless you search by their brand name, ReMarkable will not appear near the top of any organic search results. The ReMarkable is relatively expensive (~$500), so there are probably high enough margins that the company could run paid ads on terms like “electronic note taking” or “best tablet for writing.”

Paid ad listings are not better or worse than organic listings — they are just selected in a different way. As previously mentioned, organic listings favor older and more established companies. The paid listings, on the other hand, are selected on the basis of their ability to monetize at high rates per click (partially because those companies have high enough margins, but also because the ads meet customer needs through high conversion from view to purchase).

Rather than using directory listing and “tenure” as the selection tool, paid ads use “proof of monetization.”

By including paid listings, Google allows both types of selection criteria to be used by companies. Furthermore, the combination of organic and paid listings should provide searchers with more variety that will (hopefully) meet their needs.

Let’s take a look at the way a marketplace like Expedia can leverage both kinds of listings. Expedia monetizes every click that results in a purchase. As such, Expedia was never forced into adopting paid listings (unlike the way that Google NEEDED to incorporate something like paid search listings, just to keep their lights on).

Even without the pressure to use paid listings, Expedia recognized the potential of this strategy. Hotels normally pay Expedia 10–30% of the revenue generated from purchases on the site; in addition, hotels can now select a “pay-per-click” option, which lists them at the top of the search results. Many hotels choose this option, because it allows them to grab greater share (albeit at lower margins). On the consumer side, many users click on those featured listings.

The trade-off only works if users actually convert on those ads — and they often do. The hotels that try paid listings — and stick with them — must be offering something of value to the travelers.

Any method of sort order selection will be imperfect. Paid listings allow the vendors with “skin in the game” to identify the flaws of a search algorithm and to optimize their budgets for the best results.

Amazon has also realized the potential of paid listings. Amazon invested heavily in personalized recommendations, but their algorithms are far from perfect. The company now allows merchants to bid for a spot in the “sponsored listings” — which are tied to specific people and products. For example, if the algorithm misses the notion that people who like Seth Godin might also like Jeff Rosenblum’s “Friction”, then Rosenblum’s publisher can bid on the opportunity to be placed at the top of the results whenever someone searches for Godin.

In some ways, it’s fair to say that EVERYTHING listed on a site like Expedia or Amazon is an advertisement. Users search those sites for something to buy. The vendor site needs to decide which products to show at the top of the results. The vendor’s algorithm considers many factors, with the ultimate goal of maximizing total customer lifetime value per search. That end goal might result in pushing the user to a high-margin product or a low-margin product, depending on the consumer and product characteristics.

But creating the perfect algorithm is impossible. For a completely different way to sort the results, you can use a pure advertising-driven auction. After a century of experimentation, many retailers have settled on a mix of the two approaches. That’s probably the right answer, so we shouldn’t be surprised that companies like Amazon and Expedia have ended up with similar practices.

Paid social

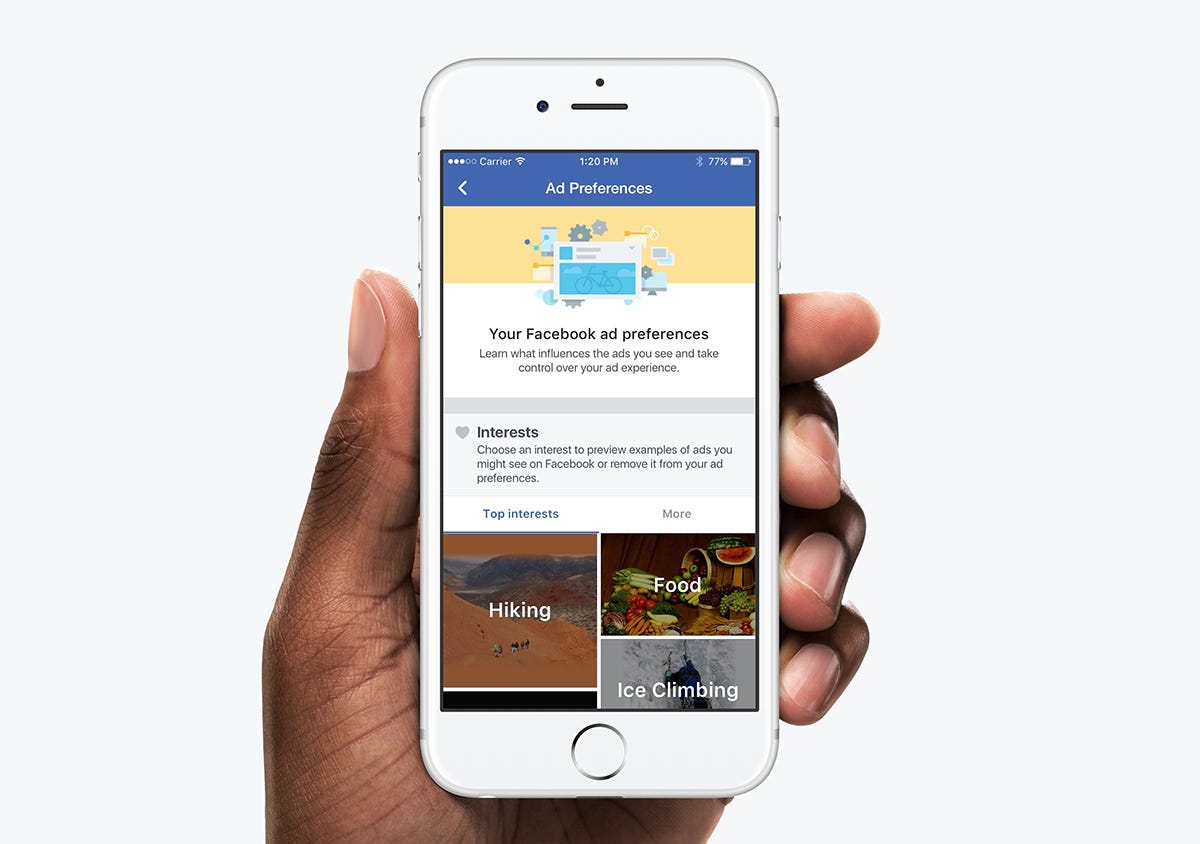

There is an “other” successful paid advertising digital channel: the ads that appear in Facebook’s newsfeed. These ads target people based on “lookalike audiences” — other users with similar attributes and behaviors. The lookalikes are usually generated by combining what Facebook knows about people (including LOTS of purchase data) with a proprietary list of a company’s own best customers.

And lookalikes work. Very, very well.

The best products to advertise on Facebook are “vitamin products” — things that try to improve a customer’s life by solving a problem the customer didn’t even know existed. If we compare the experience of visiting a bricks-and-mortar store to using an e-commerce platform, then Amazon and Google are the modern-day equivalent of shopping with a specific list of things to pick up. Continuing this comparison, Facebook ads have created a new “discovery” method that resembles the experience of browsing through various retail aisles.

There is, of course, one major difference between wandering through a physical store and scrolling through your Facebook newsfeed: personalization.

In the non-digital world, shoppers decide which stores to enter, based upon the type of products they might be interested in buying. For instance, if you need some power tools, you might visit Home Depot. If you want some new clothing, you might hit up Anthropologie.

But Facebook does not allow you to “switch stores for different discovery experiences.” Instead, Facebook uses your previous purchase history to predict which other products you might be interested in seeing. From there, Facebook relies on the merchants themselves to build advertisements that capture your attention and raise awareness of their products.

In theory, Facebook could design a “discovery” model that does not rely on paid listings. But there’s no reason to think that such a system would be any better; quite likely, the “no-paid-listings” model would be a lot worse at matching people to compelling content and relevant products.

One last note on this topic: Facebook’s model only works because of “privacy invasions.” Without personalization, Facebook’s ads would be completely untargeted; at best, the newsfeed would look like low-resolution versions of prime-time television ads.

Marketing BS ads

The topic for today’s essay was sparked by my decision to allow ads on Marketing BS.

I have established a few parameters:

There will be a maximum of one sponsor per week.

The sponsor will appear twice — once in each of the non-paywalled pieces of content.

There is no personalization, EXCEPT to the extent that advertisers are choosing to be in front of the audience that enjoys reading Marketing BS content. I hope that level of targeting will make the ads at least a little bit interesting for readers.

Let me know what you think (especially if you are a paying subscriber). Have the ads added any value? Were they destructive to your experience?

Keep it simple,

Edward

Edward Nevraumont is a Senior Advisor with Warburg Pincus. The former CMO of General Assembly and A Place for Mom, Edward previously worked at Expedia and McKinsey & Company. For more information, including details about his latest book, check out Marketing BS.