Marketing BS: J&J, Trust, and Marketing to Save Lives

Good morning,

In today’s essay, I share some marketing perspectives about the J&J vaccine fiasco.

Later this week, you can look forward to my conversation with Tom Seery, founder and current Executive Chairman of RealSelf — the leading review site and marketplace for cosmetic surgery.

—Edward

Abundance of Caution

Last week, the FDA and CDC issued a statement about the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine. In response to six reported cases of “rare and severe” blood clots, the FDA and CDC plan to review the medical evidence in greater detail:

Until that process is complete, we are recommending a pause in the use of this vaccine out of an abundance of caution.

Whether or not the vaccine actually caused the blood clots, the situation is serious: one person has died, and another has been hospitalized in critical condition. That said, these personal tragedies need to be put into perspective.

The J&J vaccine has been administered to 6.8 million people. With six cases and one fatality, that puts the vaccine-caused blood clot rate at less than one in a million and the chance of “death due to blood clot” at about one in seven million.

For context, that’s about the same risk you take each and every time you drive 10 miles. But no one is reporting how many people have died on the way to the vaccine clinic.

Nor should they.

There is a risk-reward trade-off for everything we do. To date, over 560,000 Americans (about 1.7% of the country) have died of COVID-19. The J&J vaccine appears to prevent COVID-related deaths with close to 100% effectiveness.

Let’s turn back the calendar a year and imagine two things:

Every American resident was vaccinated with J&J — before the pandemic struck.

The J&J blood clot risk is true — and at the currently estimated rates.

In that scenario, the country would have lost roughly 48 lives — instead of 560,000. For the mathematically challenged, 48 is a much, much lower number than 560,000.

So why did the FDA and CDC recommend pausing distribution of a vaccine that seems to save four orders of magnitude more people than it hurts?

The organizations’ statement provided only a vague rationale:

[T]o ensure that the health care provider community is aware of the potential for these adverse events and can plan for proper recognition and management due to the unique treatment required with this type of blood clot.

Media and medical pundits have suggested that the FDA/CDC recommendation was driven by three factors:

Cautionary Principle: When you are caught unaware of a problem, it’s better to be safe than sorry. Cautious leaders often pause situations to reconsider their previous decisions.

Credibility: The FDA is very concerned about optics — which is understandable, given that every action they take puts their “credibility on the line.”

Public Confidence: Many people are skeptical of vaccines (both in general and specifically for COVID-19). America is on the cusp of shifting from concerns with “not enough supply” or “not enough distribution” to a problem of “not enough demand.” In order to reach full herd immunity, the government needs to encourage reluctant people to take the vaccine. One way to do that: remove any doubts about the “dangers” of vaccines.

For the rest of today’s essay, I will highlight marketing lessons that correspond to each of those three points.

Cautionary Principle

There’s a clear problem with the cautionary principle: it focuses on “sins of commission” and ignores “sins of omission.” Based on current facts, pausing the J&J vaccine will result in a HIGHER number of deaths than continuing its delivery.

The possibility exists that the J&J vaccine is more dangerous than believed, so conducting more research LOOKS like a great “cautionary” step. In reality, though, the more cautious decision for RIGHT NOW would be the continued use of the J&J vaccine — that’s the action that will result in the fewest number of deaths.

This situation exemplifies the worry about making a “sin of commission.” The FDA believes they will face greater criticism for allowing something bad than they would for stopping something good.

The cautionary principle offers a clear marketing lesson: In large organizations, you are less likely to get in trouble for NOT DOING something (that results in value destruction) than you are for DOING something (that results in value destruction). This is why much smaller companies with far fewer resources can often compete with the giants. At a startup, you are not competing with the entirety of a large corporation; you are competing with a specific project manager who works from 9am to 5pm, needs six months of approvals to do anything, and doesn’t want to take any real risks. Some companies — like Google — realize this fact and try to encourage risk-taking among their employees. In contrast, large governmental organizations — like the FDA — aren’t exactly known for their spirit of risk-taking innovation.

Credibility

Concerns about “credibility” have been cited as a factor that motivated the FDA/CDC recommendation to pause the J&J vaccine. For the FDA, credibility issues are a crisis of their own making. In a recent Marginal Revolution post, Tyler Cowen argued that “Free-floating credibility” is underrated:

When the FDA announces that they have to ban a vaccine because its credibility is on the line, that very announcement puts their credibility on the line. It is a simple two-line proof. Either they are lying about whether their credibility is on the line, in which case they have wrecked their credibility with the lie. Or they are telling the truth, in which case by definition their credibility is indeed on the line...

For purposes of contrast, consider alcoholic beverages. At the federal level they are regulated by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (who are they again?), and also various state and local authorities. As a result of this unusual, Prohibition-rooted distribution of authority, alcohol does not come with nutritional labeling.

Now, in that setting, if a bunch of kids die from binge drinking, the credibility of the Bureau is not much damaged. The Bureau does not have to ban alcohol on the grounds that if it does not, the credibility of the Bureau will be ruined. The Bureau simply never put its credibility on the line in this manner… Similarly, the Department of Transportation regulates road safety (again with state and local authorities as well), but it has not put its credibility on the line when 40,000 or so Americans die each year on the roads.

The Department of Transportation attempts to make roads safer, but they do not accept “failure” for the fact that motor vehicle accidents are one of the leading causes of death in America. There is a general agreement that driving is a valuable thing for society to do, and we accept a (not small!) number of deaths in order to do that valuable thing.

An effective vaccine for COVID-19 would (obviously) be a valuable thing for society, but the FDA has decided that its credibility is on the line if even a tiny, tiny fraction of people experience serious complications from the vaccines.

Thinking about credibility brings to mind a solid marketing lesson: Don’t commit to unrealistic results. Just commit to better results than would be produced by the other options on the table.

Public Confidence

The third factor used to explain the FDA/CDC recommendation — public confidence — provides the most important marketing lessons. In fact, I would argue that increasing public confidence in vaccines is not a public health question, but rather a marketing one.

Regardless of what critics claim, most marketing is not about deceptively changing people's minds or tricking them into doing or buying something. Most marketing exists to perform one (or more) of these three functions:

Make potential customers aware the product exists.

Increase consideration for specific purchase occasions (e.g., “McDonald’s is not only a great option for lunch/dinner, but also breakfast”).

Increase trust in the product (which increases purchase likelihood and decreases price sensitivity).

That last purpose is particularly relevant in the case of J&J vaccines. By pausing the vaccine, the FDA made a fundamental error in marketing. Instead of increasing trust in the product, they have almost certainly DECREASED people’s confidence.

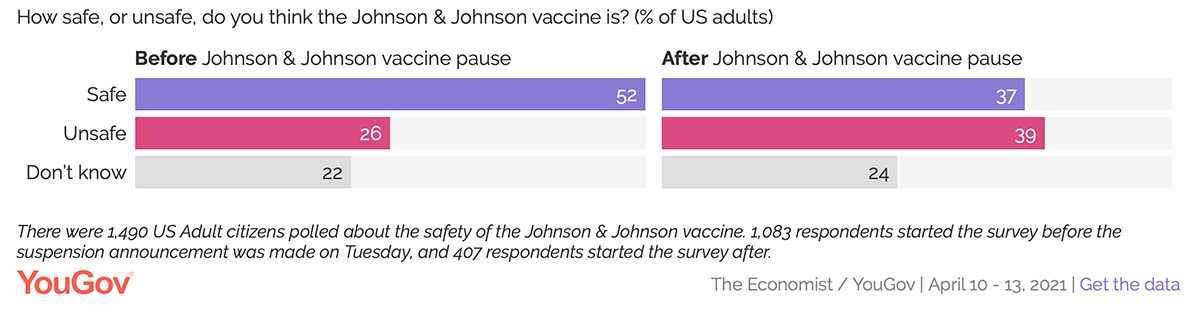

Case in point, YouGov commissioned a poll to gauge the impact of the FDA announcement:

As you can see, the poll confirmed a MASSIVE shift in public opinion. In addition to a -15% drop for “safe” and a +13% jump for “unsafe,” a plurality of respondents now believe the J&J vaccine is unsafe.

The FDA is currently “considering” the medical information about the J&J vaccine and blood clots. In the near future, they will (presumably) conclude that the vaccine IS safe. But does anyone believe public confidence in the vaccine will revert to its pre-announcement levels — let alone improve — because the FDA has communicated their commitment to cautious decision making?

As I’ve often written: most customers don’t really care about your product or your company. In similar fashion, many people are just not paying that much attention to the details of the COVID pandemic. Far too many people — including decision-makers who SHOULD be paying more attention — still believe that COVID-19 is commonly spread through contact with surfaces and/or outdoor activities. An astonishing number of COVID-driven restrictions have closed outdoor spaces before indoor ones. For example, the Canadian province of Ontario shut down playgrounds last week, only to reverse the decision the next day due to mass outrage. Likewise, during my recent trip to Disney World, capacity for the outdoor rafts to Tom Sawyer’s Island was greatly reduced — while indoor restaurants operated at close-to-normal levels.

The FDA seems to think that people will respect their decision to “exercise caution.” But nuanced messages are difficult to communicate. Many people have already internalized the oversimplified (and incorrect) message that the J&J vaccine is unsafe. Even worse, some percentage of people might have further twisted the message to “all vaccines are unsafe.” Meanwhile, for the people who ARE playing close attention to COVID news, the FDA has given one more reason not to trust the institution in general.

In the business world, employees spend (too much) time trying to convince the rest of the organization about the positive impact of their prospective plans. And if your plans involve any significant changes, you will encounter resistance. Particularly from legal counsel.

Corporate lawyers can provide useful context about the risks involved in any decision. But it’s not (usually) the legal team’s job to MAKE the decisions. A good leader should consider the legal team’s perspectives — as well as all of the other business factors — before making a decision.

Health experts — like corporate lawyers — should be providing advice to decision makers. In turn, the ultimate decision-makers should balance that medical information against all of the other facts and perspectives. But we’re now in a place where the FDA and CDC are directly issuing public announcements, which are then blindly followed by decision-makers around the country (and world).

Many of us non-epidemiologists — especially ones who started commenting on COVID-19 from the very beginning — have been repeatedly told to “stay in our lane.” (Something I’m obviously not good at…)

But the J&J fiasco was not the result of epidemiology decisions — it was a marketing problem.

When I used to work for P&G, we used to joke that no matter how stressful things seemed, at the end of the day we were just selling soap. If things went badly, no one died.

In this case, though, the FDA and the CDC’s marketing failure IS costing lives.

Maybe it’s time the FDA got out of my lane?

Keep it simple,

Edward

Edward Nevraumont is a Senior Advisor with Warburg Pincus. The former CMO of General Assembly and A Place for Mom, Edward previously worked at Expedia and McKinsey & Company. For more information, including details about his latest book, check out Marketing BS.