Marketing BS: Sales has a Marketing Problem

Good morning,

Welcome to all of the new subscribers! If you joined last week, Marketing BS alternates between weekly briefings (a round-up of news stories) and essays (my thoughts about some often-overlooked business problems and solutions).

—Edward

Sales vs Marketing

What’s the difference between sales and marketing?

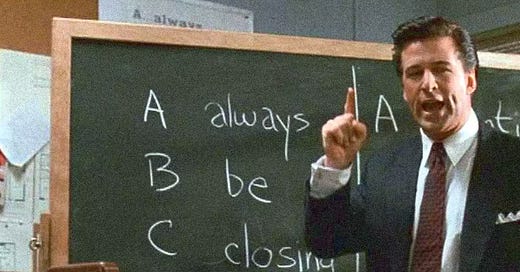

On its face, that question seems ridiculous. Sales is clearly different from marketing, right? No one is going to confuse Glengarry Glen Ross (“Always. Be. Closing.”) with Mad Men (“If you don't like what's being said, change the conversation.”). The core activities are different: sales (obviously) involves selling products or services, while marketing spans corporate messaging, customer acquisition, and more. Plus, the culture of each function is fundamentally different: the sales world demands that individual employees hit personal quotas, while the marketing world (often) assigns employee teams to work on collaborative projects.

But are sales and marketing as different as they seem on the surface? One thing, at least, is definitely clear: sales has a marketing problem.

In a July 14 Wall Street Journal article, Patrick Thomas describes the issue:

Demand for sales roles has shot up... but recruiters say they struggle to convince people to make sales a career… The struggle to find sales hires predates the pandemic and may have more to do with the types of roles people are comfortable taking these days than it does with a shortage of workers. Images of glad-handing car salesmen or “Mad Men”-style account representatives are hard to shake, recruiters say, adding that early-career hires aren’t always attracted to positions where success is measured in new business brought in.

Thomas hypothesizes that recruiting salespeople is difficult because of the profession's reputation for things like “phone-call quotas or other hard-sell tactics.” It’s important to keep in mind that sales roles can pay well (and often VERY well — it’s not uncommon for the highest-paid employee at a company to be someone in sales). That said, sales is rarely viewed as a “high-status” career. Status (and potential future status) matters A LOT when you are recruiting, especially for entry-level roles.

My personal experiences line up with the WSJ article. After graduating college, I started my career at Procter & Gamble — with the title of “Customer Business Development.” Truth be told, I had no idea what that meant. But P&G seemed like a good company, and they were offering far more money than I’d ever earned before.

During my third day on the job, my boss explained that I was actually working in sales. Terms like “Customer Business Development” were intended to make the role sound more important, but he wanted to be very clear: my job was selling soap. There was a method to the madness of P&G’s ambiguously titled job postings. For all the reasons discussed in the WSJ piece, I likely wouldn’t have applied for a role in “sales.”

But the modern world needs salespeople — a lot of them, actually. Almost 1 in 12 employed Americans work in sales; that group outnumbers marketing employees by about 50x! When you need to recruit that many people, it’s HARD to create the perception that sales is a high-status profession.

Status is often driven by exclusivity. Investment banks only recruit about 2500 new roles each year; as a result, they can be hyper-selective about choosing elite candidates. In contrast, there are 700,000 sales roles listed on ZipRecruiter right now. And we all know that if it’s easy to join a club, it might not be the type of club you want to join.

Once I started at P&G, it was clear that the coolest kids were leaving sales and getting into marketing. The company did everything it could to assure employees that sales was as important (or more so) than marketing; plus, the compensation plans were identical. Still, the status sat with marketing.

But after spending my career moving back and forth between sales and marketing, it’s become clear to me that the two functions are not as different as many people believe. For example, what’s the difference between (1) a salesperson sending out a cold email to a potential customer, and (2) the marketing team buying an email prospect list and then sending that list marketing messages? Or what’s the distinction between a salesperson sending a personalized letter and the marketing team sending out “direct mail”? Is the difference between sales and marketing just one of scale?

In some ways, marketing is essentially “sales to more than one person at a time.” And sales is the ultimate in personalized marketing.

Hospital Discharge Managers

When it comes to the differences between sales and marketing, I think it’s interesting to look at those cases when it’s unclear if a specific “activity” would fall under scope of the CMO or the CSO.

During my time at A Place for Mom, we helped people find the best senior housing solution for their older relatives. The majority of our business came from paid and organic search: someone would look for “Alzheimer's Care Austin” or “Assisted Living Communities Boston.” We funnelled those leads to our salespeople; they would work with the family until they booked the perfect fit for their needs (at which point we would be paid by the housing provider).

But advertising on Google wasn’t the only way that we acquired leads. Another option involved working with hospital discharge managers.

Imagine a senior who required a stay in the hospital. Quite often, that senior would be healthy enough to leave the hospital, but they would not be able to manage independent living at home. The hospital’s discharge planner would sometimes hand the family a list of resources (essentially the equivalent of the Yellow Pages), leaving the family to find their own solution. As a much better experience, — for the both the family and the hospital — some discharge planners introduced the family to an APfM advisor who could help the family identify the best housing solution. Bonus: the APfM services were free for the family and the hospital.

We worked hard to take that discharge strategy from basic idea to scaled-up execution. Building a successful process was difficult, but we managed to develop a very strong and resilient channel.

Was APfM’s discharge strategy a marketing channel?

The plan involved many of the standard components of a marketing channel. It had costs. It generated leads that were (relatively) easy to attribute to the channel. You could calculate the cost per lead and the cost of revenue. The leads it generated were passed to advisors. All in all, the discharge strategy definitely looks like a marketing channel.

And yet, our plan also relied on business development executives who called hospital CEOs to sell them on the idea. We had a large team of local “Community Relations Advisors” who encouraged the hospital discharge planners to send more leads. The CRAs had monthly targets of leads generated; they were paid bonuses based on hitting those targets (and they even had accelerators when they overdelivered). Plus, there was a structure of CRAs, regional managers, and directors. All of those elements look a lot like running a sales organization.

So which was it? Marketing or sales?

Both.

A Place for Mom’s “CRA model” might have been a little unconventional, but it was hardly unique. For instance, pet insurance companies can generate leads from search and television, but they also need teams of people on the ground working with veterinarians and humane societies.

Many businesses have “alternate channels” that require teams of people interacting with other humans in order to generate leads (which then get passed to salespeople). Are those businesses running a sales strategy or a marketing strategy?

Both.

These types of hybrid sales/marketing strategies are often difficult to set up, but they can produce some of the highest ROI of any marketing or sales initiatives.

Podcasts as a Sales Channel

When podcasts started to attract mainstream attention, many of the popular ones featured investigative stories (This American Life) or comedic conversations (The Ricky Gervais Show). Over the last 5 or so years, there’s been an explosion of a new genre: podcasts designed to help people and companies with their sales and marketing goals.

Some companies produce their own podcasts and treat the expense as marketing. Why advertise on a podcast when you can just create your own — the show itself functions like an extended advertisement. For example, eBay partnered with Gimlet Media to create Open for Business — a “branded” podcast about “building a business” that jumped to the top of the download charts when it launched in 2016. Other companies have tried to duplicate the model, with much less success. (And even for eBay, the true ROI for the project is unclear.)

But there is another model for in-house podcasts that works very well for B2B businesses: instead of treating an in-house podcast as primarily a marketing channel, some companies are treating it as a sales tool. The model involves a few different steps.

First, the company creates a podcast that focuses on its own industry — content they have “permission” to talk about, in that it’s closely related to their business expertise. Next, they seed the podcast with their current customer and prospect lists. Emails go out promoting the new show.

And what, exactly, is the show?

Like many other podcasts, the show features a host who interviews people in their industry. The host asks the guests to share their experiences and insights; in addition, they try to tease out generalizable lessons for the listeners (not unlike the Marketing BS podcasts). In theory, a podcast like this could help build the company’s prominence and credibility. Hopefully, the podcast would also attract new customers, but it’s very hard to generate anywhere close to the revenue you would need to justify the expense of producing a show.

And that’s where the sales element comes into play.

The podcast team identifies potential guests to interview. Some people are selected because they are entertaining or popular or will resonate with the listeners in a meaningful way. But sometimes the team reaches out to interview subjects as sales prospects.

As anyone who sells to executives will tell you, it’s HARD to get the attention of an executive. These are busy people who cannot respond to the (many) unsolicited emails and phone calls they receive. Even if your product could vastly improve their business, many executives just don’t have the time to consider your offer.

But…what if that executive was invited to appear on a podcast with a large listenership in their industry? That is a very different approach than the standard cold calls. The invitation can be pitched as a chance to help the company with its sales, recruiting efforts, etc. There’s also a clear appeal to the executive’s ego; the podcast appearance could raise the person’s profile as a thought leader in their industry (especially in the eyes of their executive peers, corporate headhunters, etc.). Many marketing executives will carve out time on their calendar for a podcast spot.

The interview itself will sound exactly like all the other episodes of the show — business stories and lessons from the executive. So how and when does the sales element enter into this podcast process? Before and after the interview, the host and guest usually connect to talk through a few logistic or technical details. Those conversations are often casual (“I love the art on your back wall”, etc.). In that situation, it’s very easy to transition from chit-chat about podcast prep to a discussion of the “podcast company’s” real business — selling their product to people like that executive. Only now, instead of appearing like a hard sales pitch, it just feels like two people learning more about each other’s businesses.

There’s no guarantee that the conversation will turn into an opportunity — let alone a sale — but it can at least help move things along to the consideration phase. The podcast is a tactic to grab the executive’s attention in a way that a piece of direct mail can rarely achieve. Once the executive hears about the product in a low-pressure environment, a good salesperson (which is what the podcast host truly is) can easily shift to asking about the executive’s needs to see if their product might be helpful.

So, who runs the podcast program? Is it a marketing initiative? This strategy needs creative producers, branding, and content development — all marketing functions. A podcast sure doesn’t look like a traditional sales organization. But targeting the interviewees and building rapport that allows for consideration of the product sure feel like sales skills.

Just like A Place for Mom’s CRA program, a successful podcast program like this will require a combined effort of both sales and marketing.

Note that a strategy like this only works as long as it doesn’t become too popular. If executives are suddenly inundated with dozens of podcast invitations, they won’t give them any more time than they do to calculators that arrive in the mail with a note asking them to “calculate the savings that Vendor ABC will bring!”

At present, most executives — at least the non-famous ones — are NOT receiving countless requests for podcast interviews. The podcast strategy works because very few companies are giving it a try. And very few companies are experimenting with unconventional ideas because they sit somewhere in the gap between marketing and sales.

To help recruit salespeople, P&G started using vague job titles like “Customer Business Development.” Maybe there’s another solution, by showing potential hires the breadth of opportunities in a sales career — ones that don’t rely on “phone-call quotas or other hard-sell tactics.”

Keep it simple,

Edward

Edward Nevraumont is a Senior Advisor with Warburg Pincus. The former CMO of General Assembly and A Place for Mom, Edward previously worked at Expedia and McKinsey & Company. For more information, including details about his latest book, check out Marketing BS.