Marketing BS: Selection Effects

Good morning,

Best wishes to everyone who lives in an American state or Canadian province that takes today off work (for one of more than a dozen differently named holidays).

In this week’s podcasts, you will hear from Matthew Kemp, principal of SCP&CO — a mid-market private equity firm. Prior to his role at SCP, Matthew was CMO of BlueGrace Logistics, and the founder of three very successful companies.

—Edward

This week’s sponsor:

BugHerd

The easiest way to collect and manage website feedback

Turn email chains and spreadsheets of vague feedback into actionable tasks. Pin feedback to elements on a website and capture the technical information to help replicate bugs and solve issues. Track feedback tasks to completion.

Corporate wellness

In November 2020, Precedence Research published a comprehensive report about corporate wellness programs. The report claimed that corporate wellness programs would grow at 7.1% per year for the next seven years — a figure that is well above projected inflation rates.

Corporate wellness is a (non-taxable) benefit for employees. Most companies try to assess the value of wellness programs in relation to other non-taxable benefits (like improved healthcare plans), as well as the general compensation offered to employees.

Wellness providers argue their programs should not be viewed as trade-offs versus other benefits. Why? Because corporate wellness programs “pay for themselves,” by reducing both employee healthcare costs and employee churn.

Some simple analysis backs up those assertions. Employees participating in wellness programs DO require lower healthcare costs and they DO churn at lower rates.

By some estimates, participants in wellness programs incur healthcare costs that are roughly 25% lower than non-participants. Plus, employees that participate in wellness programs churn at half the rate of non-participants.

Many corporate wellness programs emphasize the benefits of physical activity: increased fitness levels, improved weight management, etc. Research indicates that participants in these programs are far more likely to visit the gym (almost 2x) and take part in running events (almost 3x).

But there is a fundamental problem with “simple” analysis — it ignores any selection effects. The type of employee who signs up for a corporate wellness program is NOT the same type of person who ignores those activities. For example, think about any company-wide fitness event (walk-to-work week, yoga session, dragon boat race, etc.). There’s a good chance that the employees who CHOOSE to participate are already leading healthier lifestyles than employees who skip the company fun runs, etc.

So what happens when you replace a simple observational study (e.g., employee self-reporting) with more rigorous testing (e.g., randomized control trials)? A group of researchers attempted to answer this question; their results are astonishing.

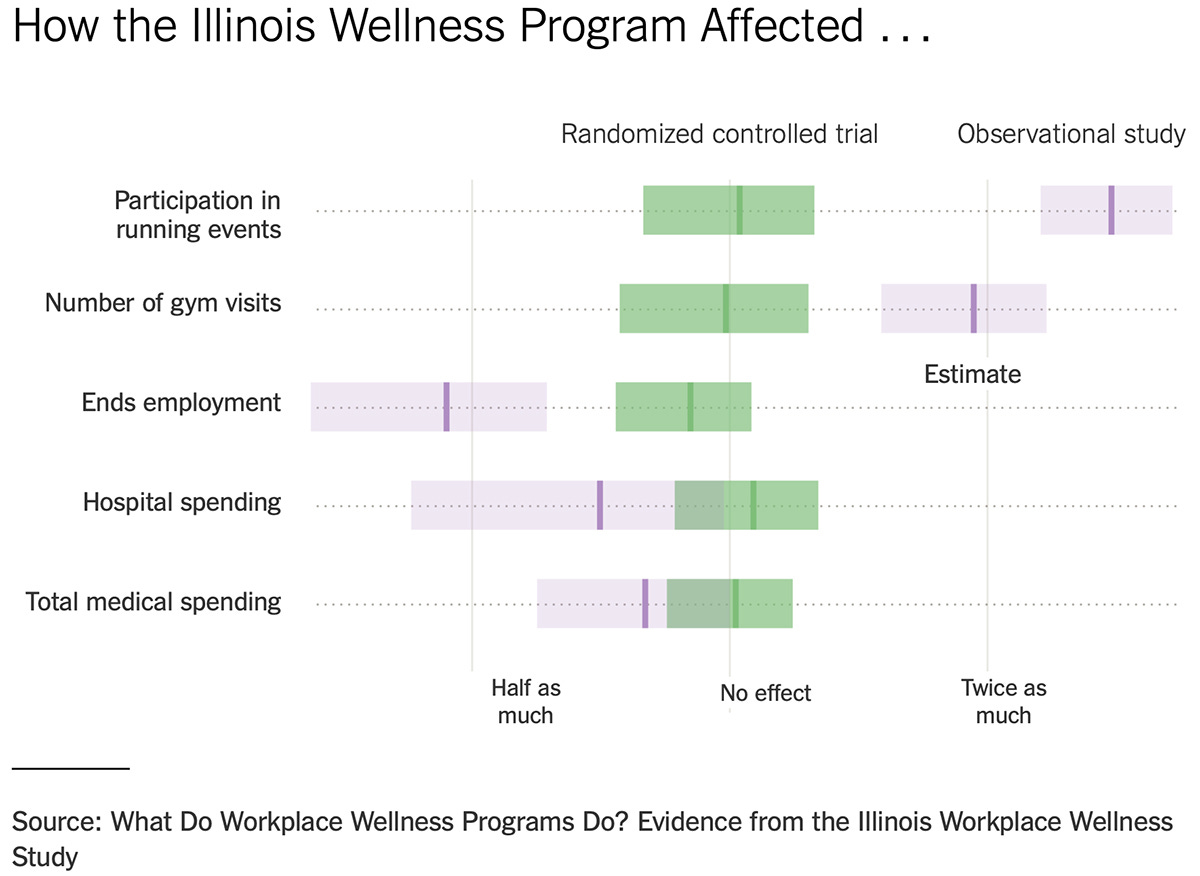

As you can see in the above chart, there are massive differences between the results of the observational studies (in purple) and the randomized controlled trials (in green). The Illinois Workplace Wellness Study reached a clear conclusion: most corporate wellness programs have “no effect.”

The lack of impact spanned all of the categories covered by the research study:

There was virtually no effect on participation in running events or the number of gym visits.

The impact on both employee churn and hospital spending was minimal.

For “total medical spending” — a major factor for employers when designing compensation and benefit plans — the corporate wellness programs provided no significant reduction in costs.

Wellness programs are not the only business practice impacted by problems with the selection effect — we see the same thing with consumer loyalty programs. You’ve probably heard that loyalty program members demonstrate greater brand loyalty and spend more money with the company. Those facts are accurate: loyalty program members ARE more loyal, and they DO spend more.

But we need to caution ourselves from going down the road of reverse causation.

Loyal customers join loyalty programs — loyalty programs do not transform flighty customers into loyal ones. In the same way, corporate wellness programs inspire health-conscious employees — they do not prompt less-healthy people to take life-changing actions.

Of course, the companies selling loyalty programs and wellness activities are happy to share “evidence” of their positive impact. And the managers that operate these programs have no incentive to pull back the curtain. If you are running a loyalty or wellness program, you don’t want to tell your boss (or your own ego) that the program provides zero measurable value to the company.

Selection effects and paradoxes

In magazines and newspapers, you’ve probably read articles about the benefits enjoyed by tall people: higher salaries, increased confidence, greater intelligence, and more.

But as noted in the previous section, we should respond to any kind of “simple analysis” with a healthy dose of skepticism.

That said, research concludes that height offers a significant advantage for people interested in reaching one certain goal: playing professional basketball. In a 2015 blog post on Slate Star Codex, Scott Alexander breaks down the numbers:

34% of the US male population is 5’9 to 6’0, so about 54 million men. There are 5 NBA players in this band. So about one in every 11 million people of this height is in the NBA.

13.5% of the US male population is 6’0 to 6’3, so about 21 million men. There are 40 NBA players in this band. So about one in every 500,000 people of this height is in the NBA.

2.35% of the US male population is 6’3 to 6’6, so about 4 million men. There are 95 NBA players in this band. So about one in every 40,000 people of this height is in the NBA.

0.15% of the US male population is 6’6 to 6’9, so about 200,000 men. There are 130 NBA players in this band. So about one in every 1,500 people of this height is in the NBA.

0.003% of the US male population is 6’9 to 7’0, so about 5,000 men. There are 160 NBA players in this band. So about one in every 30 people of this height is in the NBA.

0.00002% of the US male population is 7’0 to 7’3, which corresponds to about 45 men. There are 40 NBA players in this band. So about 8 out of 9 people of this height are in the…wait, no, that can’t be right.

Going from 6’2” to 6’5” increases your odds of playing in the NBA by 10x. Jumping from 6’5” to 6’8” improves your odds by another 25x. Adding just one or two more inches boosts your odds by 50x! And by the time you reach the 7’ mark, there are about the same number of people playing in the NBA as there are Americans of that height. (The growing international profile of the NBA complicates some of this math — teams are now searching all over the world to find ultra-tall prospects).

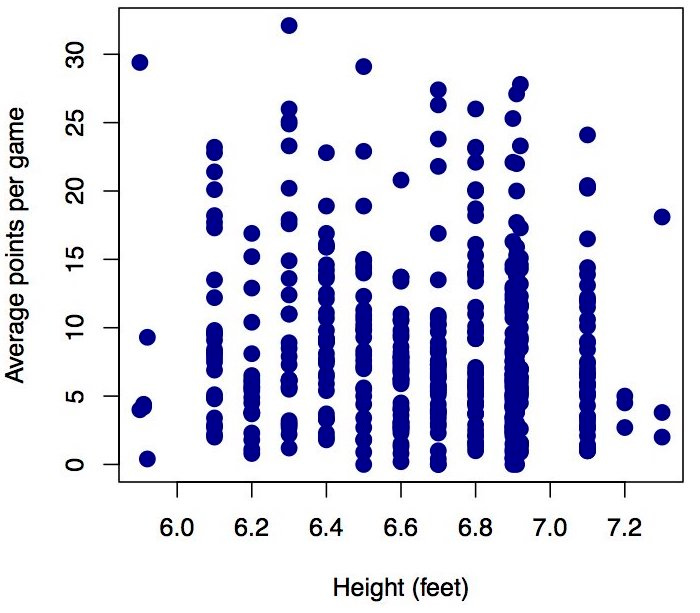

To earn a spot in the NBA, height obviously matters. But among active NBA players, height does not seem to matter at all (at least in terms of average points per game). Population geneticist Matthew Hahn created a cool visual illustration that shows the distribution of scoring by players of various heights.

How can we explain the fact that height is a major factor for MAKING the NBA, but seems largely irrelevant among players IN the league?

To help answer that question, we can look at a situation with similar effects — the hiring of management consultants. McKinsey, the leading strategic consulting firm, puts prospective employees through a grueling interview process. Candidates must endure a series of behavioral interviews (about their past), as well as “case interviews” (about problems to solve). Interviewers score each candidate using a standardized evaluation matrix. Only the candidates with consistently high scores receive offers to join the firm.

Once hired, the newly minted consultants continue to receive regular evaluations from a rotating series of engagement managers. By the end of a new consultant’s second year, their file might include five to ten performance scores. Unlike most companies, then, McKinsey possesses a standardized set of scores for each employee’s quality from both the hiring process and their on-the-job performance.

What is the relationship between a McKinsey consultant’s interview scores and performance scores? Do the highest-scoring job candidates also earn the best job scores?

Nope.

There is zero correlation between how well someone scores on a McKinsey interview and how well they perform in the role.

Earning a spot at McKinsey — like the NBA — is very difficult. Both organizations force candidates through a lot of hoops (pun intended). But once a person “gets in,” their actual performance in the position is much harder to predict. Whether a prospective candidate soared through the selection process or barely squeaked through does not appear to correlate — whatsoever — to their professional success.

There are two theories that might explain the McKinsey/NBA examples:

Berkson’s Paradox

The Good Enough Effect

Berkson’s Paradox refers to counterintuitive situations where two things that seem correlated are, in fact, not related. The Wikipedia post provides a good overview:

The most common example of Berkson's paradox is a false observation of a negative correlation between two positive traits, i.e., that members of a population which have some positive trait tend to lack a second. Berkson's paradox occurs when this observation appears true when in reality the two properties are unrelated—or even positively correlated—because members of the population where both are absent are not equally observed. For example, a person may observe from their experience that fast food restaurants in their area which serve good hamburgers tend to serve bad fries and vice versa; but because they would likely not eat anywhere where both were bad, they fail to allow for the large number of restaurants in this category which would weaken or even flip the correlation.

Berkson’s Paradox explains why a player’s height is an important part of the NBA selection process, but does not seem predictive of their scoring ability in the league. When looking for players, NBA teams consider the best available options. Height is an obvious attribute, but not the ONLY desirable trait. Over the years, there have been a number of diminutive players in the league (notable examples include Muggsy Bogues, 5’3”; Earl Boykins, 5’5”; and Spud Webb, 5’6”). In most cases, atypically short players are known for their relentless drive and impressive skills. That makes sense — the shorter a player is, the more talent they need to attract attention from teams and then earn a spot in the NBA. As a result, if a short player possesses enough drive and skill to make the NBA, then their (lack of) height is no longer an effective predictor of performance.

Berkson’s Paradox might also explain why scores during McKinsey interviews do not correlate with consultants’ on-the-job performance. Perhaps consultants are hired through a combination of their interview scores and a second “unquantified” factor. I have sat on hiring panels where some interviewers have passionately argued for certain candidates, despite less-than-stellar numerical scores. Maybe the interview scores are the equivalent of height, and some candidates demonstrate an intangible quality (the business equivalent of basketball talent) that drives their success on the job.

There is an alternative explanation to Berkson’s Paradox, something I call the “Good Enough Effect.”

The Good Enough Effect suggests that experts (like NBA talent scouts or McKinsey recruiters) can effectively determine whether someone is “good enough” or terrible, BUT experts cannot consistently distinguish between “good enough” and “great.”

According to this theory, the McKinsey interview process can eliminate the candidates who are clearly unable to make it as expensive consultants, but it cannot predict which employees will eventually become partners and which ones will wash out before their first promotion.

Now what?

The selection effect is a very important concept. We should keep selection effects at the top of our minds when reviewing any observational data that does not have a randomized control trial to measure the true impact.

Whenever you are comparing two groups — whether it’s employees, customers, candidates, or professional basketball players — and you see a difference, your first thought should NEVER be: “something we are doing must be driving that difference.” Instead, your initial analysis should try to understand how members of the two groups might be different. And the most obvious difference usually relates to the way the groups are selected.

Keep it simple,

Edward

Edward Nevraumont is a Senior Advisor with Warburg Pincus. The former CMO of General Assembly and A Place for Mom, Edward previously worked at Expedia and McKinsey & Company. For more information, including details about his latest book, check out Marketing BS.