Marketing BS: Techlash and Intra-Elite Competition

Good morning,

I hope you enjoyed the holiday weekend and summer kickoff.

After a few weeks of briefings and book chapters, I have an essay to share with you. As always, I welcome your comments and questions — you can post comments at the bottom or drop me an email.

—Edward

Backlash against Big Tech

“The future is a race between politics and technology. It may be very close.” — angel investor and entrepreneur Balaji S. Srinivasan

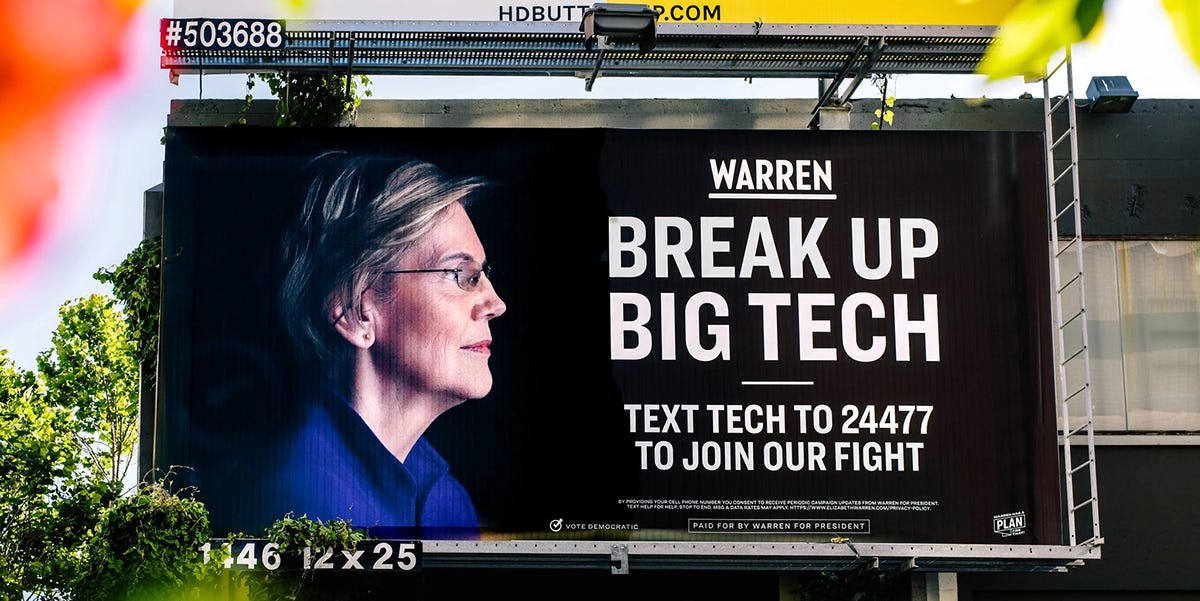

Major tech companies are facing an onslaught of regulatory, antitrust, and enforcement actions. Notice, though, that many anti-tech critics are proposing contradictory measures that would trigger unintended consequences.

Here are a few examples of the current backlash against “Big Tech”:

Google was fined €220 million by competition regulators in France. The government authority ruled that Google — by not allowing third parties to access their data — was abusing their dominance in the online advertising market. But…opening access to their data might potentially expose the company to GDPR privacy violations.

Apple has been praised for locking down third-party access on the iPhone platform, while simultaneously being accused of anti-competitive practices for stopping apps from working around the platform. So which is it? Do we want platforms to be open and share our data (and infringe on “privacy”), or closed and safe (and prevent “competition”)?

Amazon is being dragged over the coals for both “owning the platform” and then selling products on that same platform. Senator Elizabeth Warren described the company’s position as “being both a player and a referee.” In addition, merchants have voiced concerns about a catch-22 situation: they feel obligated to sell their products via Amazon, but they also worry the tech giant will copy their successful products. New laws are being drafted to prohibit Amazon from selling any of its own “private label” products on Amazon.com.

Consider the anti-tech bias of that last point. Are Amazon’s private label strategies really that different from traditional retailers?

Walmart accounts for almost half of all private label products sold in America.

In US-based grocery stores, about 18% of total sales are private label products (including more than 80% of the products sold in Trader Joe’s).

Costco’s private label brand, Kirkland, is not only manufactured in the same plants as the national brands it competes with, but Costco’s RFP requirements demand that every Kirkland product must be at least 10% cheaper and 1% better than the product it duplicates.

Why is “Kirkland” good but “Amazon Basics” bad?

Although governments seem comfortable pointing the finger at tech companies, they have struggled to implement regulations that achieve their goals without causing unintended consequences. Case in point: California’s attempt to curtail the labor practices of Uber, Lyft, and Doordash. The state’s initial laws inadvertently restricted companies’ ability to hire many other types of freelancers: writers, interpreters, coaches, comedians, musicians, and even Santa Claus himself!

The legislators quickly backtracked. But instead of re-writing the law, the government added clauses to exempt certain groups (mostly from the non-tech categories in the previous paragraph). These exemption clauses also created an opportunity for the tech companies to take down the law — the ridesharing platforms launched a (successful) voter’s initiative that added “ridesharing” and “delivery” to the list of exempted groups.

Congress appears to have learned from California’s inability to target tech — and only tech — companies. The federal government is debating laws that would only apply to companies with 50 million monthly active users (or 100,000 monthly active business users); plus, the companies must have a market capitalization greater than $600 million. These rules would stop Amazon (market cap of $1.7 trillion) from running their private label, but they would not impact Walmart ($390 million) or Costco ($170 million). (The law was clearly intended to target Facebook, Google, Apple, and Amazon, but now people are asking if it also covers Microsoft. No one seems to know.)

In theory, most laws are passed to “solve problems”; in contrast, these measures seem intended to “punish” major tech companies.

Big Tech is assumed to be guilty, and even the act of defending themselves is interpreted as more evidence of their guilt. Here’s how Representative Pramila Jayapal — a Democrat from Washington and a co-sponsor of the bills — has described tech companies’ attempts to fight back against greater regulatory control:

[Their lobbying] is making our case that they have way too much power in terms of monopoly power and in terms of money and politics.

Small business and consumers have no hope of competing with this amount of money and power.

If the only way to influence government is via lobbying, but lobbying is evidence that a company has too much power, does that mean any company that attempts to influence government is — by definition — too powerful?

Why are politicians so anti-tech?

Cynically, we could argue that anti-tech campaigns are being led by “populist politicians” — the one who don’t care about “the truth” so much as appeasing their constituents. But even with the constant attacks against Big Tech, those companies are still FAR more popular than media outlets and Congress themselves.

A 2019 Gallup survey identified the share of US adults that trusted institutions “a great deal/quite a lot.” Television news (20%) and Congress (11%) held the two bottom spots. Compare those dismal numbers to the favorable/unfavorable ratings of many tech companies (as listed in a Vox Media survey):

My theory: tech companies are not being attacked because they are unpopular — they are being attacked because they are not unpopular enough.

Intra-Elite Competition

Jack Goldstone is a sociology professor at the University of California, Davis. In his 1993 book — Revolution and Rebellion in the Early Modern World — he argued against the traditional belief that revolutions were the result of conflict between social classes. Instead, Goldstone proposed, tensions were sparked by competition WITHIN the upper class — a phenomenon that Goldstone named “intra-elite competition.”

University of Connecticut professor Peter Turchin picked up on Goldstone’s theory and articulated the ways that intra-elite competition is impacting modern America. Turchin defines the elite in America as the “top 1%” — but not just the top 1% by income. He suggests a more generalized top 1% that includes, “elected politicians, top civil service bureaucrats, and the owners and managers of Fortune 500 companies.” Turchin argues that the number of potential elites in America — measured in terms of both wealth and education — has been significantly rising over the last few decades. But because “being elite” is a zero-sum concept (limited to the top 1%), the growing number of potential elites means that the potential for conflict is also growing.

I think the concept of “intra-elite competition” provides an interesting lens to view the current backlash against big tech.

In my Marketing BS career guide, I described three “vices” that drive career decisions:

Money

Power

Fame

As you climb the corporate ladder, your money, power, and fame often grow in tandem (whether that was your aim or not). Different career paths can emphasize one or more of those three vices. In some ways, we can imagine that each vice has its own “elite hierarchy.” The tech industry — and business in general — follows the “money vice.” The top of this ladder includes people like Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, and Bill Gates. Yes, these people (and others like them) hold plenty of power and fame, but that power and fame is largely the result of having more money than anyone else.

For the “power vice,” you will find the American political class. US presidents can easily amass a fortune — the Obamas are worth more than $70 million — but the power comes from the presidency, and the fame and money follow the power.

When I searched for the “most famous people in the world,” the lists included moguls like Gates and presidents like Obama. But most of the people on the list could be described as “celebrities” — people who are famous for being famous, rather than for their money or power. These lists are dominated by artists and athletes (people like The Rock, Will Smith, Drake, Jennifer Lopez, and Tiger Woods). To the extent that Dwayne Johnson has the ability to accumulate power or money, it’s because of his fame.

Very, very few individuals — even “elite” individuals — will ever obtain the levels of success held by Bill Gates, Barack Obama, or The Rock. But there are many people who will run a large company (money), win a political election (power), or write a column in the New York Times (fame).

Reaching the ranks of the elite requires effort and dedication. That drive rarely disappears when “elite status” is obtained. Jealousy can be a powerful motivator. There are countless stories about rich people — with more money than they could ever spend — breaking laws to amass even greater wealth. (As one example, a former managing director at McKinsey — with a net worth in the hundreds of millions — served two years in prison for insider trading. He was apparently bitter about not being part of the billionaire’s club).

Jealous ambition also compels some elites from one “vice hierarchy” to try and conquer another one. Celebrities run for political office. Former politicians join corporate boards. Musicians become venture capitalists. Fame translates into power or money. And once people have money, they often want to rub shoulders with the famous and powerful.

The most obvious way to raise your status involves accomplishing greater and greater things. But because “elite-ness” is a zero-sum concept, there is another way to boost your own status — try to lower the status of rival elites. With that in mind, we should not be surprised that many powerful and famous people seem hell bent on knocking down the status of the tech world’s nouveau riche.

Revolving Participants of Intra-Elite Competition

The criticisms levelled against tech companies might be new(-ish), but it’s certainly not the first time that media outlets and political leaders have denounced the top companies of their day.

In The Great A&P and the Struggle for Small Business in America, author Marc Levinson traced the decades-long crusade against the grocery company. Levinson describes the anti-A&P campaigns as “mostly political” — fueled not by the concerns of consumers (who loved the ability to buy all their groceries in one place), but by the criticisms from mom & pop shops who ran standalone butcheries, fishmongers, fruit stands, or dry goods stores (and who felt they couldn’t compete against the grocery giant).

As Mark Twain quipped, “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” Today’s tech companies are getting the same treatment as yesterday’s grocery chains.

Intra-elite competition is a battle to hold the highest status. Unlike wealth creation, status is a zero-sum game: there is no difference between increasing your own status or decreasing everyone else’s.

The concept of status battles — both within one’s own group and between rival groups — helps explain many of today’s political and cultural tensions. In the context of a status battle, the phrase “Black Lives Matters” doesn’t mean that white lives are irrelevant; instead, BLM is a slogan intended to increase the status of African Americans. And the people who push back with “all lives matter” rhetoric aren’t (necessarily) claiming that black lives do not matter — they are trying to resist the relative lowering of their own status. Similarly, campaigns to “defund the police” do not (usually) aim to eliminate police forces altogether, but rather communicate a desire to “lower the status of police.”

Intra-elite competition is often more intense than battles between distant adversaries. If you’ve ever worked for a large company, you have probably encountered some executives who worried more about their departmental colleagues than rival businesses.

And as much as Republicans are worried about China, they are more worried about the Democrats (and vice versa). Silicon Valley investor Mark Andreesen’s recent interview with Noah Smith drew a connection between US-China competition and the anti-tech backlash in America:

...China has a strategic agenda to achieve economic, military, and political hegemony by dominating dozens of critical technology sectors — this isn't a secret, or a conspiracy theory; they say it out loud. Recently the tip of their spear has been networking, in the form of their national champion Huawei, but they clearly plan to apply the same playbook into artificial intelligence, drones, self-driving cars, biotech, quantum computing, digital money, and etc. Many countries need to consider very carefully whether they want to run on China Inc.'s technology stack with all of the downstream control implications. Do you really want China to be able to turn off your money?

In the meantime, the West's technology champion, the United States, has decided to self-flagellate — both political parties and their elected representatives are busily savaging the US technology industry every way they possibly can. Our public sector hates our private sector and wants to destroy it, while China's public sector works hand in glove with its private sector, because of course it does, it owns its private sector. At some point, we may wish to consider whether we should stop machine-gunning ourselves in the foot at the start of this quite important marathon.

Andreesen is not the only one perplexed at the targets of our rage. David Brooks, a columnist at The New York Times, recently asked “Why is it okay to be mean to the ugly.” Brooks cited some interesting evidence: ugly people are less likely to receive job interviews, less likely to receive a loan, and less likely to gain admittance into top graduate programs than attractive people.

Brooks quotes a study that found more people report being discriminated against because of their looks than because of their ethnicity. Why is no one fighting for the rights of the ugly? Brooks argues that attractiveness is a fundamental element of American society:

It’s very hard to buck the core values of your culture… A society that celebrates beauty this obsessively is going to be a social context in which the less beautiful will be slighted.

Our pagan culture places great emphasis on the sports arena, the university and the social media screen, where beauty, strength and I.Q. can be most impressively displayed.

Brooks is correct that our society equates attractiveness (and strength and IQ) with high status. But allow me to take his theory one step further: Because attractiveness is equated with high status, there is no high-status elite group that is affiliated with unattractive people. As such, there aren’t any groups of elites fighting to lower the status of attractive people. No politicians are leading the charge against “Big Beautiful.”

Intra-Intra-Elite Conflict

The concept of intra-elite conflict can sufficiently explain the anti-tech positions of the media and politicians, but there are other, more subtle effects worth exploring. Intra-elite conflict is not restricted to battles across the Money/Fame/Power divisions — there are battles from within each hierarchy, as well. For instance, Democrats and Republicans are both in the “power column,” but they clearly battle one another as fiercely (or more fiercely) than they do the “fame” and “money” elites.

And even within a group like the Democrats, we can see internal status battles. For a good example of these intra-party tensions, consider Amazon’s process for selecting their “HQ2.”

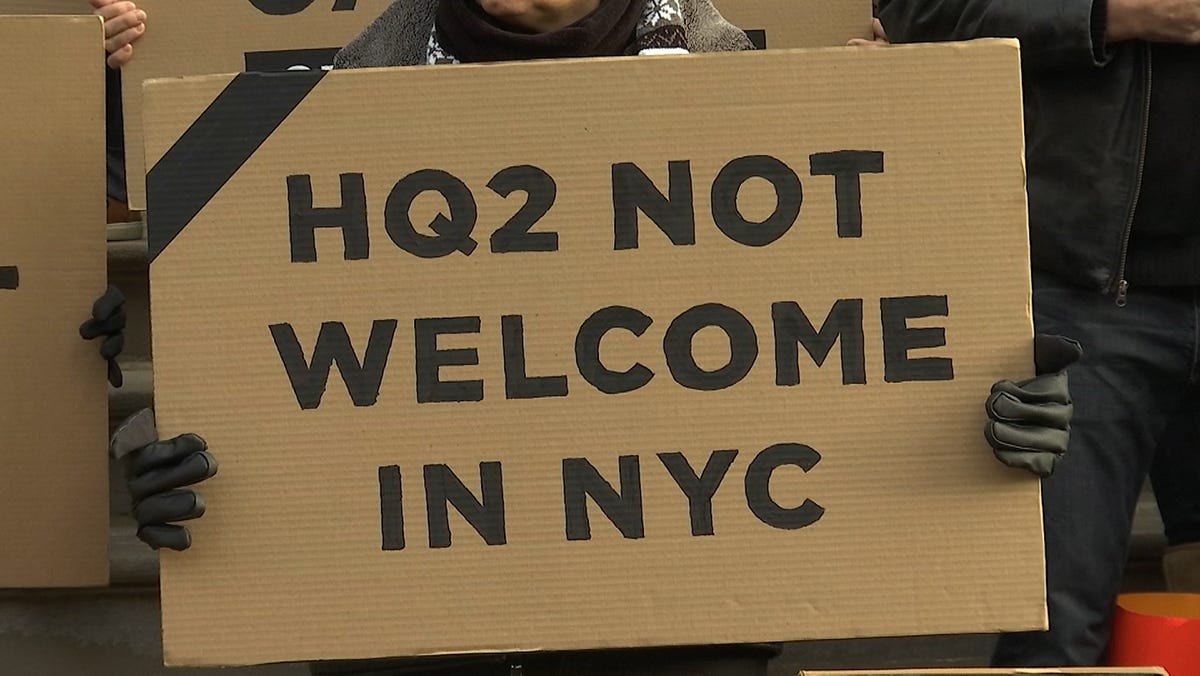

Journalist Brad Stone details the entire process in his wonderful book, Amazon Unbound: Jeff Bezos and the Invention of a Global Empire. When Amazon invited municipalities and regions across North America to “apply” for the site of the company’s second headquarters, many politicians derided Amazon’s overt show of power.

Let’s take a step back and think about reality TV. In The Bachelor, women fight for the attention of a single man. After (most) seasons wrap up, producers select a woman who was NOT picked by the bachelor, and then make her the central focus of her own show, The Bachelorette. In that series, the gender roles are reversed, with the men vying for her affection. Although the woman herself is relatively unchanged, her status skyrockets — all because the power dynamic around her was inverted.

Amazon — just like the producers of The Bachelor/ette — recognized the ways that shifting the parameters for a situation can impact the status hierarchy. Normally, cities would negotiate with Amazon as one of many companies looking to expand into the region. But Amazon flipped the script and became the star of the show, with dozens of cities forced into the role of desperate suitor.

Many politicians — who had been previously accustomed to calling the shots in their city — were not happy about the Amazon-caused status flip. But, just like the men in The Bachelorette, the politicians had no other option but to compete in a very public process.

For politicians, the very act of “applying” for a massive corporate investment would reduce their status. Except, of course, for the politicians who managed to secure HQ2 in their backyard; those leaders would see their status increase.

After a (too) long process, Amazon selected Washington, DC and New York City as “co-winners” for HQ2 (along with Nashville as the national operations headquarters).

Amazon’s arrival in NYC would have added thousands of high-paying jobs (as well as thousands of additional service jobs). As a result, the announcement provided a huge status boost for the politicians who successfully won the bid — thereby lowering the relative status of many other competing politicians in the region.

When you are clamoring to attain high status, there is nothing worse than being excluded from “the room where it happens.” The politicians who weren’t involved in the selection process began to demand greater concessions from Amazon. Brad Stone described the situation as “an immediate outpouring of dissent mounted by local officials who were out of the loop and taken by surprise by the news.”

Eventually, Amazon gave up on NYC — leaving Washington, DC as the sole winner of Bezos’ billionaire bake-off. When you hold the highest status, you always have the option to just turn around and walk out the door.

The tech backlash continues, even though there are occasional wins for the largest companies. For example, an antitrust case against Facebook was recently thrown out of court (which caused their stock price to jump). But don’t expect that case to be the end of the trouble for Facebook, or any of the other tech giants. The battle for elite status is not something that will be wrapped up in a single court case. Intra-elite conflicts have been playing out for as long as societies have had elitist hierarchies. As more and more people in our society become educated and (relatively) wealthy, the battles for status will only increase.

Our ability to recognize the intrinsic drivers of these conflicts may not change the outcomes, but it can at least give us a better understanding of the dynamics. And maybe those of us who are not part of the ultra-elite can use these examples to help understand when our own motivations shift from genuine altruism to self-motivated status chasing.

Keep it simple,

Edward

Edward Nevraumont is a Senior Advisor with Warburg Pincus. The former CMO of General Assembly and A Place for Mom, Edward previously worked at Expedia and McKinsey & Company. For more information, including details about his latest book, check out Marketing BS.