Marketing BS: Trump, Vegas and Plausible Deniability

Good morning everyone,

I expect that overall worker productivity reached an all-time low last Wednesday, as many of us watched news coverage of the Capitol Hill invasion with a combination of shock, horror, and derision.

In today’s essay, I will look at some common reactions to the event through the lens of standard marketing practices.

—Edward

Today’s essay is sponsored by Pulsar

Stop doing generic social listening: tap into Audience Intelligence

Different communities talk about the same topic differently.

Carry out instant conversation analysis + audience segmentation in just one tool with audience intelligence platform Pulsar: understand the public conversation, identify the top communities in your audience, and glean actionable creative & media insights to power your marketing.

Mayhem on Capitol Hill

Of all the ink spilled about the insurrection, I recommend Boston College history professor Heather Cox Richardson’s newsletter post, which contains a concise end-of-week summary as well as some insightful perspectives. She argues that Wednesday’s infamous event included not only “play acting” that got carried away (see: a fur shawl and horned helmet), but also some very dangerous elements that should not be taken lightly:

Reuters photographer Jim Bourg, who was inside the building, told reporters he overheard three rioters in “Make America Great Again” caps plotting to find Vice President Mike Pence and hang him as a “traitor”; other insurrectionists were shouting the same. Pictures have emerged of one of the rioters in military gear carrying flex cuffs — handcuffs made of zip ties — suggesting he was planning to take prisoners. Two lawmakers have suggested the rioters knew how to find obscure offices.

I have no interest in litigating last week’s events, but I believe there is real value in connecting those actions with two ideas that regularly appear in Marketing BS essays:

People do not care about privacy. Plus, the privacy we do have is much better than most people think.

Everybody lies. But we tell us ourselves that it’s only spin.

Privacy

We’ve all heard people express concerns about privacy violations from social media, internet browsers, smartphones, and other tech companies. “Sooner or later,” the pundits say, people will get fed up and stop using these products and services. In reality, though, our collective behavior suggests that we’re not as cautious about our personal privacy as we claim — quite the opposite, actually.

If there were ever a time that you would want to hide your privacy, how about this situation: you break into the Speaker of the House’s office, vandalize her property, and steal sensitive documents. And yet, Richard “Bigo” Barnett — who committed all of those acts and more — posed for photos and posted them on his own social media accounts.

The participants who entered Capitol Hill might not have believed that they were breaking the law (perhaps due to their understanding of First Amendment rights to freedom of assembly, etc.). But surely these people realized — especially as glass doors were shattered — that there was at least a CHANCE they could get in trouble for their actions. Even some legislators and lawyers seemed unconcerned with posting “rebellion selfies” on their public social media accounts.

Many of these same people are paranoid that a vast government-media-tech conspiracy is perpetrating a coordinated attack on their values, finances, and health. If THESE people don’t care about their privacy, do you really think your average customer does?

At the same time, the aftermath of the attack has exposed the real-world limitations of privacy-invading systems. On television shows like CSI, police authorities review surveillance videos, “enhance” the blurry images of faces, and then run them against a massive database of every citizen. The culprits would be identified before the next commercial break.

And TV shows aren’t the only place that we’ve heard about these high-tech detection systems. Numerous media stories have contributed to our belief that sophisticated facial recognition technology exists:

The Washington Post broke a story about the FBI and ICE’s use of state driver’s license photos for facial recognition searches.

The Verge reported that advocacy groups have demanded that Google, Amazon, and Microsoft refuse to provide governments with access to their facial recognition software.

CNN detailed the city of Portland’s decision to ban the use of facial recognition technology by city departments and public-facing businesses.

But unlike the video surveillance tactics used on TV shows, the government does not have a super-intelligent system that finds people in nanoseconds. Following the Capitol Hill chaos, the FBI’s software was apparently unable to cross-reference the video recordings against their database of people’s images. Instead, the FBI resorted to an old-fashioned method for identifying suspects — wanted posters (albeit with a modern twist: sharing the images on social media and asking the public for help).

Even though the current government cannot effectively track citizens’ every move, the very idea of a widespread facial recognition network is terrifying. And yet, many of America’s most paranoid people did not seem to care about taking even the simplest precautions to conceal their identity. (The overlap between Trumpists and COVID-deniers probably explains the lack of surgical-style masks, but few people disguised their appearance with common items like bandanas, goggles, hats, etc.).

Everybody Lies

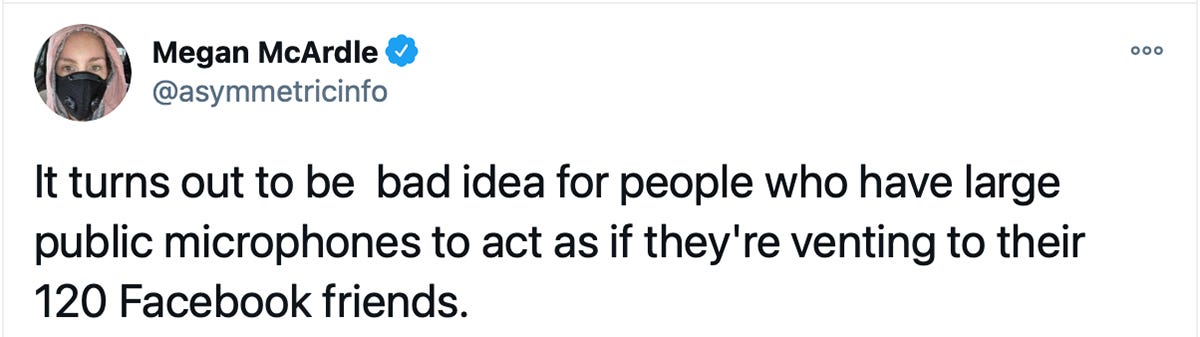

Last Friday, Washington Post columnist Megan McArdle posted an insightful Twitter thread:

The Capitol Hill infiltration did not occur in a vacuum. The participants might not have planned to “storm the hill,” but they at least coordinated about the importance of gathering in a particular place, at a particular time, on a particular day. Case in point: some people wore sweaters that read “MAGA Civil War” and printed with the date (dispelling any notions of spontaneity).

And for two months leading up to last Wednesday’s events, many of these people developed a sense of urgency about overturning the results of an election they believe was fraudulently conducted. Of course, the narrative of election irregularities was constructed and communicated by a number of leaders, including both conservative politicians and media personalities.

Few, if any, of those leaders will face legal consequences for what happened last week. You can expect to hear leaders state they never — in a million years — expected that their enthusiastically loyal followers would ACTUALLY take action. During Trump’s hourlong address at the pre-riot rally, he told the audience: “We're going to have to fight much harder. We're going to walk down to the Capitol… Because you'll never take back our country with weakness. You have to show strength, and you have to be strong.” Rudy Giuliani spoke even more bluntly, stating the need for “trial by combat to settle the election.” Both men could claim that they were speaking figuratively — not literally.

They can maintain plausible deniability.

Before you judge these would-be demagogues too harshly, consider what marketers do on a regular basis — all as part of the standards of the profession.

What Happens in Vegas

Any marketer knows that your advertising campaigns cannot include outright lies or baseless claims. In my own career, I’ve participated in long-drawn-out negotiations with corporate lawyers about the specific words that would (or would not) be acceptable for an ad.

But things get complicated when people INFER, rather than directly state, an idea or fact. To maintain “plausible deniability,” marketers — just like politicians — need to walk a fine line of legality and morality.

Virtually every beer commercial features attractive people having fun. The advertisements never say that “drinking Coors Lite will result in a sexually charged party where people find you attractive.” And yet, we all understand that beer companies are clearly suggesting that fantasy. Marketers often develop campaigns that consider the “hierarchy of needs” — universal needs that humans want to have fulfilled.

And what are those needs and wishes?

In The Sage Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology, Alastair Davies discusses his research about people’s PRIVATE desires. Participants in a study were presented with a list of 48 options; each person was asked to select the 10 wishes they most desired.

More than half of the study’s participants expressed a desire “to deeply love a person who loves me” and for “peace on Earth.” As you can see from the above graph, there are some notable differences between the answers of men and women — especially for “the ability to have sex with anyone I choose” (even without the graph, you can probably guess the outcome…).

Savvy marketers know how to leverage this information, by pushing their brands to the top of people’s pyramid of desires. Take soap, for example. Soap is a simple product that we use to clean our body. But we also associate soap with cleanliness, which we associate with attractiveness.

And so, smart marketers try to connect their soap products with people’s “desire to be perceived as attractive.” No corporate legal team would ever approve a tag line like, “This soap will give you the ability to have sex with anyone you choose.” But watch a commercial for Axe Body Spray — you would be hard pressed to walk away thinking that was not the message being inferred.

In 2003, Las Vegas’s creative agency, R&R Partners, came up with the iconic slogan, “What Happens Here, Stays Here.” The message was later refined to “What Happens in Vegas, Stays in Vegas.”

What — exactly — is this ad copy inferring?

Surely the ad campaign does not imply that visitors can do ANYTHING in Vegas without facing consequences. If you rob a bank, for example, you should still expect the FBI to track you down. During your trial, claiming that “it happened in Vegas” will not be an acceptable legal defence. You can’t even steal in Vegas — the casinos use some of the most sophisticated security measures in the world.

The Vegas tourism bureau would never admit what the ad REALLY infers, but we all know the answer: you can travel to Vegas and cheat on your partner. Based on their ads, there is very, very little room for any other interpretation.

We don’t think twice about the Vegas slogan, because we believe that their implication is “just words.” The city doesn’t explicitly endorse infidelity.

In similar fashion, many of Trump’s defenders claim that his speeches are not dangerous. No matter how wild his statements might be, they are — after all — just words.

Like the soap marketers who create sexually suggestive commercials, Trump knew exactly what he was doing when he coined the phrase “Make America Great Again.” People listening at home could interpret the slogan to convey a time period when white people maintained a firmer grip on society. Or when organized (Christian) religion occupied a more prominent position in our lives. Or when blue collar work was held in higher esteem. Or “MAGA” could mean none of those things. The ambiguity of the slogan provided political flexibility and plausible deniability. You don’t need legal approval to say “Make America Great Again,” because the phrase is not fully defined — on some levels, it’s not really saying anything at all. Just like “What happens in Vegas.”

Earlier in this essay, I highlighted the fact that our collective privacy concerns are overstated. Likewise, the persuasiveness of advertising campaigns is MUCH lower than people believe. Marketing can be very effective at helping people remember a brand, but not to influence people to take significant — and previously unconsidered — actions. The Vegas slogan, clever as it was, could not influence otherwise-committed people to cheat on their partners. (And “It happened in Vegas” is no better a defence in divorce court than a criminal one).

I leave you with one final thought, from Aaron Sibarium, the editor of Free Beacon:

When something clearly bad occurs, it’s easy to blame other people. Perhaps we should also pause and think about what lessons we could learn — and apply — to our own profession.

Keep it simple,

Edward

Edward Nevraumont is a Senior Advisor with Warburg Pincus. The former CMO of General Assembly and A Place for Mom, Edward previously worked at Expedia and McKinsey & Company. For more information, including details about his latest book, check out Marketing BS.