Vaping, Juul, and “Bad Companies”

Welcome to Marketing BS, where I share a weekly article dismantling a little piece of the Marketing-Industrial Complex — and sometimes I offer simple ideas that actually work.

If you enjoy this article, I invite you to subscribe to Marketing BS — the weekly newsletters feature bonus content, including follow-ups from the previous week, commentary on topical marketing news, and information about unlisted career opportunities.

Thanks for reading and keep it simple,

Edward Nevraumont

Juul’s Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Week

Last week, Juul — the leading manufacturer of e-cigarettes — announced the departure of CEO Kevin Burns, as well as the suspension of all digital, print, and television advertising. Altria (who owns 35% of Juul) also ended their merger talks with Philip Morris. I don’t think it’s possible to overstate the awfulness of Juul’s past two weeks.

I often begin Marketing BS newsletters with a quote about a major news story. This week, I struggled to decide WHICH disastrous Juul scandal to lead with.

In case you couldn’t keep up with all of the attacks on Juul, here’s a quick summary of some regulatory crackdowns:

President Donald Trump proposed banning flavored e-cigarettes and imposing tighter regulations on the entire industry.

The FDA accused Juul of making illegal advertising claims.

Congress threatened to subpoena Juul for documents.

Senators Mitt Romney and Jeff Merkley drafted a bipartisan bill that would ban e-cigarette flavors other than tobacco, create new design standards, apply tobacco taxes onto e-cigarettes, urge the Department of Health and Human Services to oversee an e-cigarettes campaign, and make it more difficult to refill vape cartridges.

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced emergency plans to ban all flavored e-cigarettes in the state.

Some other countries acted with even greater force. India imposed a national ban on e-cigarettes. In addition, China halted all Juul sales, just days after the product launched in the country.

Juul’s troubles rapidly expanded from the regulatory sphere into the commercial one. CBS, CNN, and other media companies pulled all advertising for vaping-related products. Omnicom severed all relationships with Juul, ending their production and distribution of television commercials for the company. Walmart decided to stop selling e-cigarettes from all US stores.

Just when Juul executives thought the situation couldn’t get any worse, California prosecutors launched a criminal investigation into the company’s marketing to young consumers.

The bottom line: Juul doesn’t have a lot of defenders right now.

Won’t Somebody Think of the Children!

If Juul executives wonder why they’re on the hot seat, they should remember that they’re the ones who started the fire (with e-matches, presumably). Many organizations have expressed concerns that e-cigarette companies appear to target children and teenagers — sidestepping the regulatory and advertising barriers that limit young people’s access to cigarettes. A team of researchers at Stanford University released a comprehensive investigation into Juul’s marketing practices. The report offers a compelling argument that Juul intentionally targeted teenaged consumers:

JUUL’s advertising imagery in its first 6 months on the market was patently youth oriented. For the next 2 ½ years it was more muted, but the company’s advertising was widely distributed on social media channels frequented by youth, was amplified by hashtag extensions, and catalyzed by compensated influencers and affiliates.

….During its meteoric growth, JUUL posted a prodigious volume of advertisements via social media, promoted them via paid influencers, and distributed its messages to a wide community via hashtags. The credibility of JUUL leadership denials of youth targeting is undermined by their diligent efforts to expunge their social media history. [Emphasis mine]

And how did teenagers respond to the advertising campaigns?

In short, they put their parents’ caution in an e-cigarette and inhaled it.

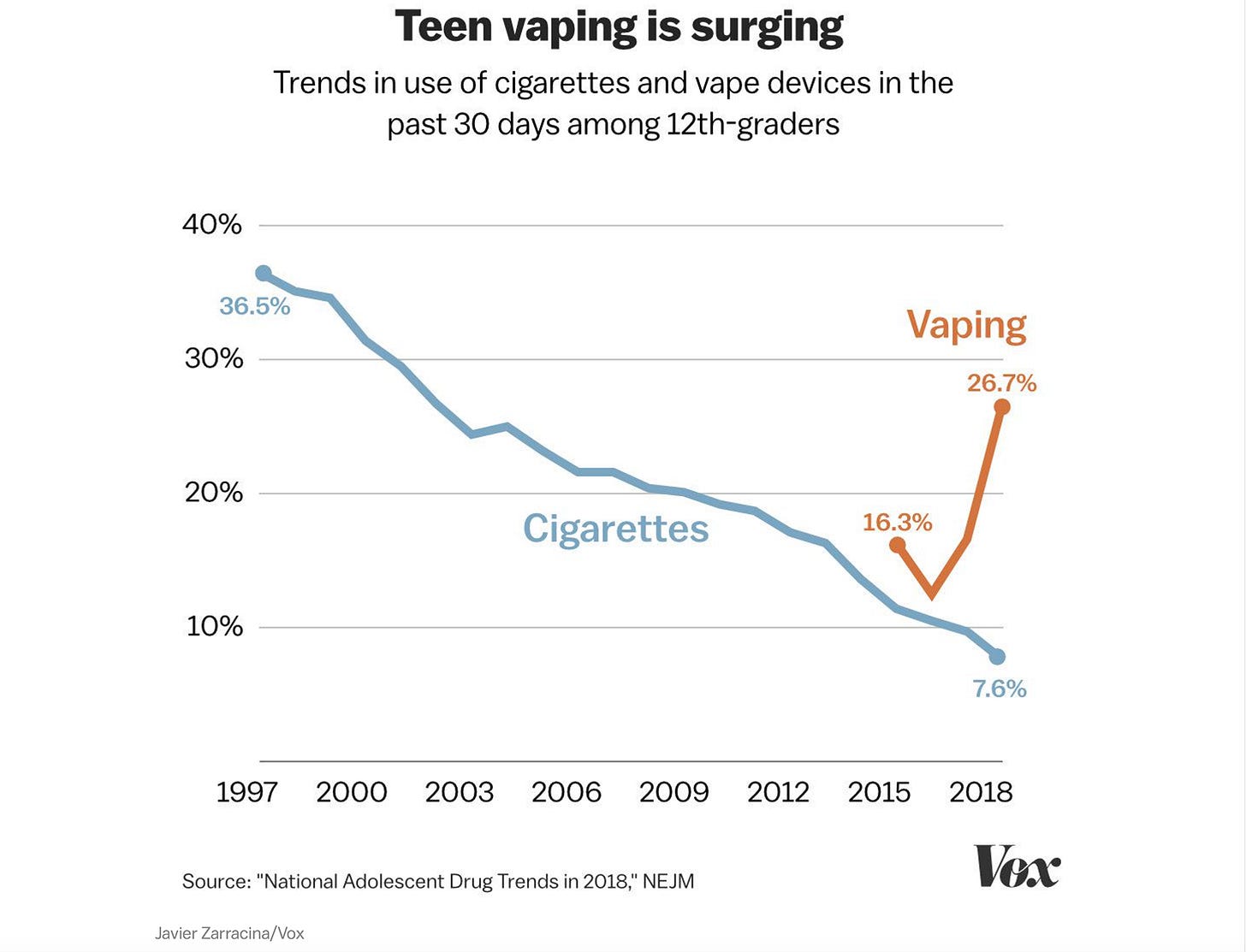

In just a few years, vaping culture quickly took hold within high schools. According to the best estimates (courtesy the New England Journal of Medicine), more than 1 in 4 American 12th-graders used a vaping device within the past 30 days.

Notice that cigarette use among 12th-graders has steadily declined for more than a generation. When vaping gained traction as a mainstream product, some analysts hypothesized that e-cigarettes might deter teenagers from using traditional cigarettes. So far, the evidence suggests that cigarette use continued to follow its downward trajectory, unimpacted by the rise in vaping. In other words, e-cigarette companies essentially created a new (and sizable) consumer base among teenagers.

Once again: Juul doesn’t have a lot of defenders right now.

Vaper Madness

As vaping gained popularity, various organizations and businesses scrambled to make up policies on the fly. Could you use e-cigarettes in a restaurant? What about school? How about an airplane? In the big picture, though, vaping was treated less like an epidemic and more like a social irritant — something akin to loudly talking on cell phones in restaurants.

What factors have ignited the recent problems for Juul?

Generally speaking, Juul has encountered a common predicament for companies with meteoric growth — with greater attention comes increased scrutiny. And as more people looked into Juul, they discovered concerns with not only the company’s business operations, but also vaping’s health risks.

More specifically, the most damning issue for Juul has been media coverage about the dangers of vaping. As of September 27, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have identified 805 lung injury cases and 12 deaths attributed to vaping-related devices.

The CDC reports — along with parental hysteria and political outrage — have crystalized the narrative that vaping is among the worst things in the world. And when a company, idea, or personality gets assigned to the “bad” category, all nuance is lost.

But how “bad” is vaping, really?

Here is the concise answer, direct from Johns Hopkins Medicine: “vaping is less harmful than traditional smoking” (but “vaping is still bad for your health”).

Remember, though, that society has collectively decided that vaping is “bad.” As such, even reputable organizations are susceptible to misstating (or at least misunderstanding) the facts. Back in June, the Journal of the American Heart Association published a study claiming that e-cigarettes were a risk factor for causing heart attacks. As described by Jacob Sullum in Reason:

Based on data from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH), the researchers found that vapers were twice as likely to report heart attacks as subjects who had never smoked or vaped. … But according to Brad Rodu, a tobacco researcher at the University of Louisville, most of the e-cigarette users who reported heart attacks had them before they started vaping, which makes [the] causal inference logically impossible. [Emphasis mine]

Think about this situation: supposedly objective researchers concluded that e-cigarettes had contributed to causing heart attacks in people who had never tried vaping! How could qualified scientists overlook such an obvious logical fallacy? Because…once something falls into the “bad” category, all sense of nuance disappears. Even trained experts can only see what they want to believe. Plus, social trends can exert significant amounts of pressure on people. Perhaps the researchers consciously worried about being labelled as “pro-vaping” or maybe being accused of working under the control of “big e-cigarette.” More likely, though, I expect they subconsciously affirmed the ideas that were socially popular.

We witnessed a similar lack of nuance at last week’s congressional hearings on vaping. Vicki Porter, the only “pro-vaping” witness during the hearing, testified that e-cigarettes helped her quit smoking: “Vaping is a health miracle to me. Not safe, but less harmful.”

What was the congressional response to her statements?

Rep. Rashida Tlaib asked Porter if she was “a conspiracy theorist,” before (falsely) asserting that the impact of second-hand smoke is “worse than directly smoking cigarettes.” Rep. Debbie Wasserman-Shultz emphasized that Porter is “not a public health expert”; Wasserman-Shultz also praised anti-vaping witnesses for, “speaking truth about this, because the long-term effects are very dangerous.”

Notice the confusing relationship between vaping and smoking. Science confirms that vaping is bad for your health, but not as bad as smoking. And yet, San Francisco recently banned all sales of e-cigarettes — while continuing to allow the sale of regular cigarettes. Likewise, Walmart was heralded for pulling e-cigarettes from their shelves, but they continue to sell various tobacco products.

To understand the current anti-vaping mania, let’s step back and remember how society shifted its views on marijuana. For many years, marijuana was also “bad” without any sense of nuance. The claims about marijuana’s impact were so over the top that they seem laughable in retrospect. Consider this description of Reefer Madness, the 1936 anti-marijuana propaganda film:

The opening scene of Reefer Madness — the 1936 anti-marijuana propaganda film that’s now a cult classic — zooms in on a high school principal alerting his students about what’s plaguing the nation’s youth. “Not alcoholism, not opium, not cocaine,” he declares, “but marijuana is the worst drug corrupting the youth of America.” The message? Weed is pure evil. Public enemy No. 1. A narcotic that destroys the human spirit, transforming men into violent monsters and women into ravenous whores. Watching the film now, it plays as broadly comedic, but back then it was deadly serious.

We might laugh off the outrageousness of Reefer Madness as a reflection of its era, but don’t forget that during the 1980s, the Partnership for a Drug-Free America ran commercials warning teenagers that marijuana would turn their brains into fried eggs.

In educational campaigns, quotes like this one were not uncommon:

“I was given my first joint in the playground of my school. I’m a heroin addict now, and I’ve just finished my eighth treatment for drug addiction.”

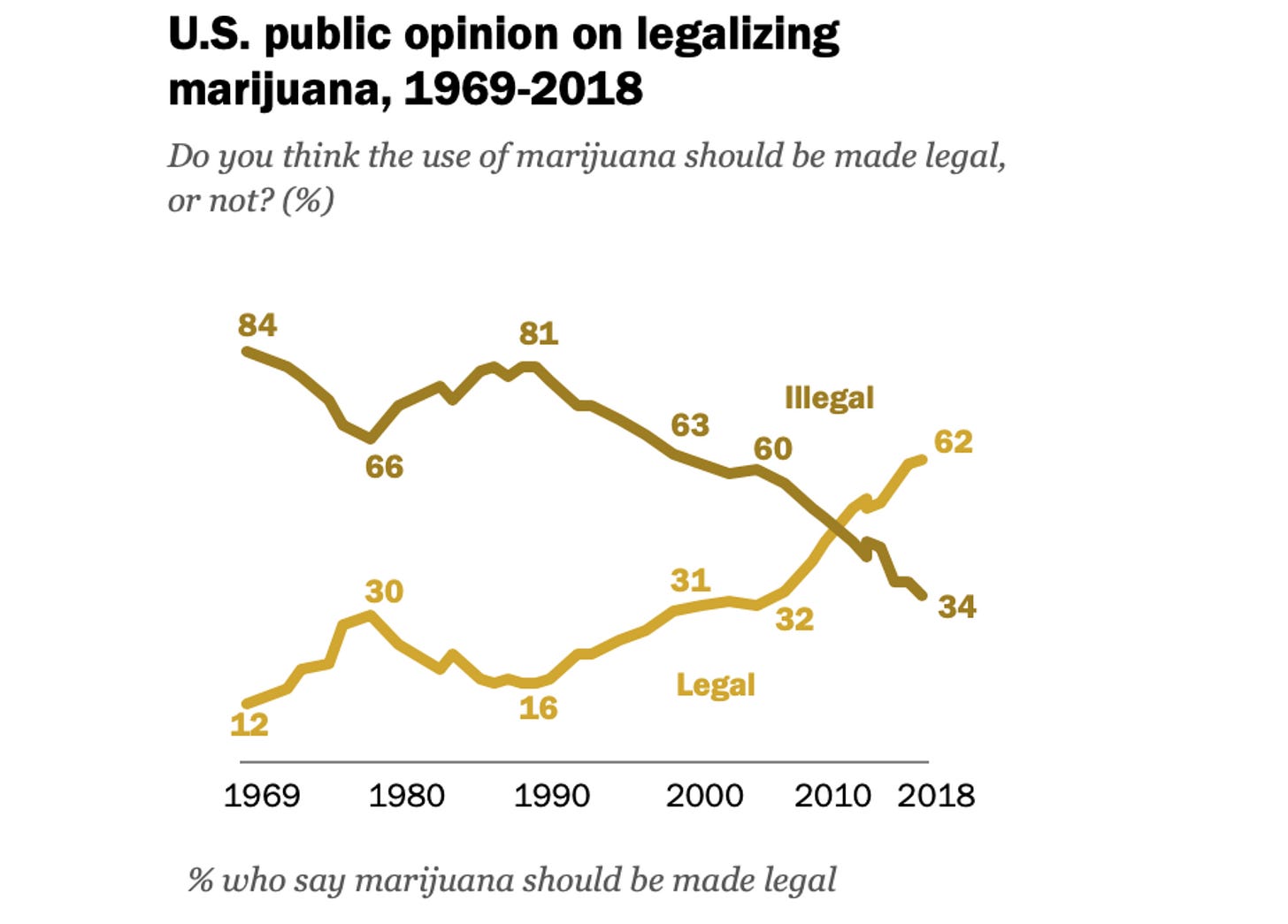

Over time, for a variety of reasons, social attitudes on marijuana changed. Take a look at the gradual shift in opinions from 1969 to today (from Pew Research Center):

In 2019, more than half of US states have either legalized or decriminalized the sale of marijuana for recreational purposes.

Of course, evaluating the health benefits or risks of a product is — unlike social opinions — highly nuanced. Just last week, the CDC released an update about the recent “epidemic” of vaping-related illnesses and deaths. The information suggests that “nearly 77% of cases of patients with vaping-related lung injuries had used products containing THC” (the principal psychoactive constituent of cannabis).

Wait a minute…more than three-quarters of the people injured by vaping devices were actually using them for marijuana and not (exclusively) nicotine? With that information in mind, do you expect anyone to backpedal on e-cigarette bans? What about rolling back marijuana legalization? Of course not. Because vaping is “bad.”

Even if you are aware of social desirability bias, the influence is hard to break. I would never consider working for a tobacco firm, but when I was approached for a role at a marijuana investment company, I thought enough about the opportunity that my wife and I sat down to discuss the idea.

In the business world, the social perceptions of a product can change everything. Juul was harshly criticized for “targeting kids” by releasing nicotine products with flavors like watermelon and strawberry lemonade. But how are flavored nicotine products any different than marijuana-infused edibles, like gummi bears and chocolate brownies?

According to the court of social opinion, tobacco smoking has been “bad” for at least a generation. Marijuana evolved from “bad, without nuance” to “if not good, then at least socially progressive.” As for vaping, well, it’s moved from “cool new thing” to “absolutely the worst thing.”

Who’s the Next Contestant for “Your Company is Bad”?

While trawling through the negative stories about Juul, I stumbled upon this tweet:

I think that’s one of the most perceptive takes I’ve seen (especially coming from someone with 61 followers). Yes, Juul is bad because they sell poison to kids, but they are ALSO bad because of their status as a tech company. In the same way that Juul holds an ignominious distinction as a “bad” company, perceptions of the entire tech sector are rapidly shifting from “good” to “bad.”

Twenty years ago, many jurisdictions resisted big box retailers like Walmart and Home Depot, as well as chains like Starbucks and Old Navy — these companies were “destroying” small businesses and historic neighborhoods. Today, many North Americans cannot imagine life without those companies (one community recently launched a petition to save their local Starbucks).

In recent years, we’ve seen rising levels of vitriol aimed at Facebook, Amazon, Google, and Apple. After WSJ broke the story about Amazon’s possible manipulation of its search results (a topic I covered here), venture capitalist Benedict Evans shared some insightful points in his newsletter:

I'm normally pretty skeptical of Amazon's business practices, but this whole private label argument baffles me: for over 100 years big retailers have looked at best-selling products and made their own to cut out their suppliers, and then used all means at their disposal to push them (placement and display, coupons, loyalty cards etc). Now Amazon is following the playbook, and somehow it's different — because it uses ‘data’ (yet Sears was using data like this a century ago) and ‘scale’ (yet all e-commerce including Amazon is only 10% of US retail). It's certainly worth looking at how Amazon might abuse a strong market position where it has one (for example, in books), but getting outraged at the discovery that Amazon does ‘retail’ is not a good starting point.

Without question, Amazon receives regular criticism for using strategies that other retailers have followed for a century. Evans emphasizes people’s perception of data and scale (which he rightly dismisses as a poor differentiator). I think there’s an even more influential factor: society has formed the idea that Amazon is a “bad” company. Consequently, all of Amazon’s actions should be analyzed through the lens of their inherent “badness.” We see this play out every day in the political forum — citizens vociferously approve or reject policy ideas on the basis of partisan affiliation, rather than thoughtful evaluation.

Juul has earned the lion’s share of negative media coverage lately, but Amazon isn’t far behind. Check out this sampling of Amazon-related stories that circulated over the last few weeks:

Amazon is manipulating sort order to maximize profit. (Marketing BS)

Amazon is selling unsafe products. (WSJ)

Amazon is paying employees to tweet positive opinions about their working conditions. (NYT).

Amazon is flooded with fraudulent customer reviews. (Consumer Reports)

Amazon delivery is bad for the environment. (Axios)

Amazon delivery drivers sometimes hit pedestrians. (Buzzfeed)

Amazon delivery drivers sometimes urinate in their own vehicles. (Business Insider)

Amazon distributed copies of Margaret Atwood’s new novel days before its official release. (CNN)

A wide range of groups — media outlets, corporate analysts, and political officials — have reached the consensus that Amazon should be placed into the “bad company box.” As a result, all of Amazon’s missteps (or ANY of their actions, really) will be subjected to sharp criticism. Facebook, Google, and Apple all find themselves in similar “bad company boxes.” The Big Four tech companies face innumerable governmental inquiries into their business practices. In a recent Axios article, Kia Kokalitcheva compiled a long list of governmental investigations. Spanning both jurisdiction (federal and state) and well as focus (privacy, antitrust, and other potential violations), here are some highlights:

The Federal Trade Commission AND the House Judiciary Committee are both (separately) looking into Facebook’s historical acquisitions.

The FTC hit Facebook with a $5B fine for privacy violations.

The Department of Justice is investigating Google’s possible antitrust violations.

Google agreed to pay $170 million as part of a settlement with the FTC, due to YouTube’s illegal collection of children’s personal information.

The House Judiciary Committee is probing all four companies for anti-competitive practices.

I have no interest in defending any of these companies’ operations or actions. That said, when it comes to the tech giants, I believe that most people are replacing nuanced analysis with black/white thinking. Finding negative stories about the Big Four is easy, but I would argue that has less to do with their “badness” and more to do with their size. If you look closely at any large company, you can quickly spot examples of dishonest or incompetent behavior.

Moreover, once a company is relegated to the “bad box,” any of their positive attributes are overlooked. For instance, some people have successfully used e-cigarettes as a way to quit smoking, a strategy partially affirmed by a major UK report (although, to be clear, no vaping-related products have received Food and Drug Administration approval as smoking cessation devices).

While YouTube’s algorithms are regularly pilloried for the ways they recommend videos featuring (and targeting) children, the platform has also revolutionized the spreading of tacit information — something that empowers marginalized communities around the world. The company’s flaws are repeatedly flagged by major media outlets, but its benefits are confined to blog posts on Medium.

One final example: Facebook was (rightly) thrown into the “bad box” for its data practices during the 2016 Cambridge Analytica scandal. But as Ben Thompson of Stratechery explained in a post: “...the data the Trump campaign obtained is no different than the data the Obama campaign obtained (legitimately, because Facebook hadn’t fixed its API) in 2012.” At the time, Obama’s use of Facebook was considered both ethical and brilliant. By 2016, though, that data use (and data user and data provider) breached people’s threshold of acceptability — a line that moved over the four years.

Riding the Dragon

During my time at A Place for Mom, multiple state governments were passing legislation that targeted senior housing referral services (i.e., our own company). In many cases, the new regulations were proposed at the behest of local mom & pop agencies that were getting beat by our scale. Washington State imposed regulations making it illegal for companies to provide support for the purposes of finding senior housing, UNLESS the potential resident signed a specific document. To be clear, this new law was NOT about protecting seniors or saving them money, because referral services were always free for the families. Requiring a signature posed a major challenge for the large companies, which regularly conducted business over the phone (and asking a senior to print, sign, and fax a document added a clear friction point). The smaller, regional agencies, on the other hand, usually met with seniors in person, so securing a signature was no big deal.

The law caused substantial churn within our company’s client base. Our technology team devised a new workflow, incorporating DocuSign into the assistance process; this electronic signature satisfied the legal requirements to serve seniors in Washington. Due to A Place for Mom’s scale, we could absorb the investment of the new technology. All of our other “national” competitors took another approach — they just gave up on the state.

What was the end result? The local agencies still existed, but the competitive landscape was significantly BETTER for us, because all of the national rivals left the market. When similar laws were being considered in other states, A Place for Mom continued to voice its opposition. I asked our legal counsel, “Why are we fighting these laws? We’ve already built a solution in Washington. Couldn’t we replicate that model everywhere else and watch the legislators take out our competitors for us?”

I will never forget her response: “Once you unleash the legislative dragon, you can’t guarantee you will be able to ride him where you want him to go.”

In the tech industry, some of the Big Four’s competitors have decided to ride the dragon. Many companies are confident that public opinion has not placed them into the “bad box”; consequently, they seem comfortable adding fuel to the fire that’s currently roasting Facebook, Amazon, Google, and Apple. Here are a few examples:

Genius (a site that catalogues song lyrics) accused Google of stealing its content.

YouTube’s competitors, suppliers, and even AdTech networks are appearing as cooperative witnesses before Congress.

Snapchat collected a full dossier on Facebook (nicknamed“Voldemort”) and delivered the materials to the Department of Justice.

In mid-2018, a new non-profit organization — Free and Fair Markets — started a national campaign attacking Amazon’s practices. The non-profit group identified itself as a grassroots organization supported by regular American citizens. Upon closer investigation, however, The Wall Street Journal discovered that Free and Fair Markets received the bulk of its funding from Walmart, Oracle, and Simon Property Group. In addition, the WSJ questioned the truthfulness of the non-profit organization’s membership:

The grass-roots support cited by the group was also not what it appeared to be. The labor union says it was listed as a member of the group without permission and says a document purporting to show that it gave permission has a forged signature.

In these politically polarized times, an “anti-tech” perspective seems to be one of the few things that bring together Republicans and Democrats. How many other topics align the perspectives of both President Donald Trump and Senator Elizabeth Warren?

Why do Warren and Trump concur on this issue? Because both of their political bases share a similar viewpoint. In the same way that “everyone” now opposes vaping, “everyone” is also united in their distrust of “big tech.” A recent poll of people’s opinions toward tech companies appeared in Vox (based on polling from Data For Progress and YouGov Blue); the results are fascinating.

I can’t think of another issue where the opinions of Democrats, Republicans, and Independents lined up so closely.

Whenever you feel worried that America is divided, remember that at least we all agree on one thing. Facebook, Amazon, Google, and Apple are in the same boat as Juul — bad companies that need to be punished.

Escaping the “Bad” Label

Once a company finds itself in the “bad box,” climbing out can prove very difficult. That said, there are a few examples.

In some cases, a “bad” company’s status changes not because of any strategic decisions, but due to the sinking fortunes of a competitor. For a period of time, Twitter was the “bad” social media platform — a reputation earned due to poor performance, “fake news,” and unchecked harassment. By no means has Twitter fully escaped the “bad box,” but they’ve certainly received less scorn ever since the shame spotlight turned its focus to Facebook.

In other instances, companies (and people) have successfully shed their “bad” image through some rehabilitative behavior. Consider the shifting perceptions of Microsoft and Bill Gates. Once considered the Evil Empire, the company has moved from the “bad box” to model citizen. Microsoft’s market capitalization of $1.06 trillion is almost double Facebook’s $526 billion, but they have managed to evade the Big Tech takedown. Microsoft was “bad” in the 1990s, and is now “good”; as such, there is no need to investigate — even though they oversee a social network (LinkedIn) and a search engine (Bing), control an operating system (Windows), and leverage their market position to push their own inferior products (Microsoft Teams versus Slack).

How did Bill Gates and Microsoft flip the public consensus? Although billionaires usually erect mansions in the “bad box,” Gates has garnered a reputation as one of the world’s great philanthropists. Microsoft’s switch was largely driven by a new CEO (Satya Nadella) and his dramatic steps to increase transparency within the company. (In the big picture, there were probably hundreds of factors that nudged Microsoft’s reputation in the positive direction, but Satya’s actions were the most notable).

A company in the “bad box” can’t count on the embarrassment of rivals or the shifting of public opinion; thus, it’s incumbent on the organization to take proactive steps when trying to climb out of the box. In some ways, though, I realize that this suggestion sounds like saying “you just need to go out and make a viral video.” If the tasks were that simple, then every video would go viral and no one would stay in the box.

Let’s return to Juul’s backlash. The company (accurately) spotted trouble on their horizon. With the increased scrutiny on teen use of vaporizers, Juul realized that their business might go up in smoke. So they attempted some proactive maneuvers, as noted in an article from The Wall Street Journal:

Juul has tried over the past year to position itself as a responsible actor in an industry with few rules. It overhauled its marketing, halted retail-store sales of its fruity flavors that young people favor and introduced a checkout system to curb illegal sales to minors.

Juul “flooded” Washington with lobbyists and they launched education programs that warned young people about the dangers of vaping. Instead of reassuring regulators, though, Juul’s charm offensive raised suspicions — it resembled the strategies used by tobacco companies half a century earlier. If Juul’s strategy had worked, they might have been hailed as brilliant. Instead, their frantic actions flopped and have been held up as an example of corporate folly.

Uber is another company desperately trying to scratch its way out of the “bad box.” In addition to firing their controversial CEO and bringing on Dara Khosrowshahi, the company has spent over $500 million on “image repair campaigns.” While Uber is not in the crosshairs the way they were in 2017, “People familiar with the company’s market research data told the [Washington] Post that despite these efforts last year, public perception of Uber hasn’t shifted much from its crisis-heavy days.”

Amazon seems to be making conscious choices to improve their reputation. During last week’s launch event, they announced dozens of new Echo products, but they also showcased new ways to delete data. David Limp, Amazon’s Senior Vice President of Devices and Services, explained the company’s renewed focus on privacy:

We’re investing in privacy across the board. Privacy cannot be an afterthought when it comes to the devices and services we offer our customers. It has to be foundational and built in from the beginning for every piece of hardware, software, and service that we create.

The week prior, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos stated the company’s pledge to operate on a carbon neutral basis by 2040. Earlier this year, Amazon made some noise about offering an internal minimum wage of $15, as well as investing $700 million in a training fund for their warehouse workers. In reaction to the news about employment conditions, I took a cynical position in a Marketing BS post, writing that the announcement sounded like it was just “marketing activities [to] raise awareness and consideration for Amazon.” I still believe my statement is true, but maybe Amazon’s announcement was about more than creating awareness — perhaps it was part of a strategic plan to get out of the “bad company box”? If so, it’s not clear that Amazon’s announcements are working any better than Uber’s investment.

Final Thoughts

There doesn’t seem to be a playbook for getting out of the “bad box.” Do your best. Hope for the best.

My only recommendation: at least recognize when social opinion is turning. That way, you won’t be overwhelmed when it feels like every media hit is negative.

It’s not paranoia when they really are out to get you.

Keep it simple,

Edward

If you enjoyed this post, I encourage you to click the little heart icon below my bio. Thanks!

Edward Nevraumont is a Senior Advisor with Warburg Pincus. The former CMO of General Assembly and A Place for Mom, Edward previously worked at Expedia and McKinsey & Company. For more information, including details about his latest book, check out Marketing BS.