Marketing Lessons from Spider-Man vs. the Avengers

Welcome to Marketing BS, where I share a weekly article dismantling a little piece of the Marketing-Industrial Complex — and sometimes I offer simple ideas that actually work.

If you enjoy this article, I invite you to subscribe to Marketing BS — the weekly newsletters feature bonus content, including follow-ups from the previous week, commentary on topical marketing news, and information about unlisted career opportunities.

Thanks for reading and keep it simple,

Edward Nevraumont

Marvel and Marketing

Even if you’ve never picked up a comic book in your life, chances are high that you’ve seen — or the very least, heard of — some of the films in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. The Avengers. Black Panther. Iron Man. These aren’t just movies anymore — they’re events.

For the audience member, Marvel has created a source of entertainment that is notable for its prolific abundance, as well as its artistic excellence. For the business analyst, Marvel has provided a case study for the ages: how to leverage marketing strategies into a billion-dollar media empire.

In today’s newsletter, I’ll provide some context for Marvel’s climb to the top, followed by a handful of lessons that marketers can learn from adults wearing masks and capes.

Let’s begin with last week’s bombshell. An article in Deadline broke the news that Sony and Disney reached an impasse over the rights to Spider-Man movies:

Marvel Studios president Kevin Feige won’t produce any further Spider-Man films because of an inability by Disney and Sony Pictures to reach new terms that would have given the former a co-financing stake going forward. A dispute that has taken place over the past few months at the top of Disney and Sony has essentially nixed Feige, and the future involvement of Marvel from the Spider-Man universe, sources said.

In case you’re not the kind of person who attends comic book conventions, here’s a quick primer on how Marvel rose from bankruptcy to supremacy:

In the 1990s, Marvel Comics found themselves in dire financial straits.

To generate cash, Marvel sold the movie rights to many of their characters. Among the highlights: X-Men, Fantastic Four, and Daredevil to 20th Century Fox; Hulk and all theme park attractions east of the Mississippi River to Universal; Iron Man to NewLine; and Captain America to Artisan.

Most of these contracts expired, allowing Marvel to regain control of the movie rights for most of their second- (and even third-) tier properties. Flagship franchises like X-Men and Fantastic Four were still held by 20th Century Fox.

That brings us to 1998 and a negotiation that changed Hollywood forever.

Marvel — still strapped for money — offered Sony the movie rights to nearly ALL of the remaining characters under their control. The price? $25 million.

A 2018 article in the WSJ shared the details of that pitch:

In 1998, a young Sony Pictures executive named Yair Landau was tasked with securing the theatrical screen rights to Spider-Man. His company had DVD rights to the web slinger but needed the rest in order to make a movie.

Marvel Entertainment, then only a famed name in the comic-book world, had just begun trying to make film deals. The company was fresh out of bankruptcy and desperate for cash, so its new chief, Ike Perlmutter, responded with a more audacious offer. Sony, he countered, could have the movie rights to nearly every Marvel character — Iron Man, Thor, Ant-Man, Black Panther and more — for $25 million.

Mr. Landau took the offer back to his bosses at Sony, whose response was quick and decisive, he recalled in an interview: “Nobody gives a shit about any of the other Marvel characters. Go back and do a deal for only Spider-Man.” [Emphasis mine]

Worst decision in the history of the entertainment industry? It surely ranks high on the list.

Sony and Spidey

After rejecting the offer to purchase movie rights to most of the Marvel library for $25 million, Sony acquired the rights for Spider-Man alone, at a cost of $10 million, plus 5% of the gross box office and 50% of the revenue from consumer products.

So…how did the Spider-Man deal work out for both sides?

From 2002–2007, Sony produced a trilogy of Spider-Man movies, starring Tobey Maguire. Under the terms of the agreement with Marvel, Sony would lose the rights to Spider-Man if they didn’t release a movie every five years. In 2012 (five years after their last film…), Sony released The Amazing Spider-Man, a “rebooted” (i.e., repetitive) version of the webslinger’s adventures, featuring Andrew Garfield. A sequel followed in 2014. Despite earning massive sums at the box office, Sony’s five films were met with good-but-not-great responses: neither critics nor moviegoers respected the movies as much more than a reason to eat popcorn in the summer.

As for Marvel? Well, what a difference a decade makes. When Disney acquired Marvel in 2009, only two movies has been released (with a few more already contracted for production with other studios). Disney poured resources into the Marvel Cinematic Universe, resulting in an unprecedented schedule of activity: 2–3 theatrical releases each year, with characters and plots that connected the movies together into one continuing saga. Even though Disney was limited to using Marvel’s less marketable characters (Hawkeye, Black Widow, the Guardians of the Galaxy, etc.), the films shattered box office expectations. In contrast to Sony’s Spider-Man movies, the MCU transcended the cynical perceptions of blockbusters: even casual moviegoers developed emotional rapports with the characters. Moreover, the films earned the credibility of critics — 2018’s Black Panther received an Oscar nomination for Best Picture, a rare achievement for an action movie.

Along came a spider…

By the middle of this decade, both Sony and Marvel recognized the value in a potential partnership: Sony could use some assistance in boosting the artistic merits and popular appeal of their movies, while Marvel could further energize the MCU with the addition of the legendary wall-crawler.

In 2015, Sony and Marvel reached a deal, with the following terms:

Disney would assume creative control of Spider-Man, incorporating him into the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

Sony would shoulder all the costs and reap all the profits (less 5% of gross) from any stand-alone Spider-Man releases.

The end result? A win-win arrangement that resulted in two stand-alone Spider-Man movies, as well as the character’s appearance in three other MCU films.

For Sony, Spider-Man produced a financial windfall. The latest movie (2019’s Spider-Man: Far from Home), collected more than $1 billion from box offices around the globe, making it not only the top-grossing Spider-Man film, but also the highest grossing film in Sony’s 90-year history! Furthermore, from a quality perspective — which significantly impacts the long-term value of a franchise — the pair of MCU Spider-Man films earned generally better scores than the five Sony ones on aggregator sites like Rotten Tomatoes, Metacritic, and IMDb.

For Disney, assigning a precise financial value to the partnership is complicated, because it’s impossible to isolate Spider-Man’s box office appeal from the mass popularity of the MCU series of films. On the creative side, Disney valued Spider-Man highly enough to set up the superhero as one of the core characters for the next cycle of theatrical releases.

Stuck in a web of negotiations

Despite an artistic marriage that seemed to work for both sides, Marvel and Disney announced their break-up last week.

At this time, details about the divorce are scarce. Recall that under the terms of the 2015 deal, Sony assumes all costs for stand-alone Spider-Man movies, but receives all of the profits (less 5% of gross).

Based on details from an article in Polygon, comments in a Marvel Cinematic Universe Reddit thread, and other reading, here’s my best guess of how the negotiations unfolded:

Disney: “We noticed that your last Spider-Man film crossed the $1 billion threshold at the box office, but we only received 5% of the gross. Can we chat about ways to structure a fairer deal?”

Sony: “No thanks. We think the current arrangement benefits everyone.”

Disney: “What if we share production costs 50/50 (or maybe 70/30) and then we split the profits equally?”

Sony: (stops returning Disney’s phone calls).

Disney: “Given that our artistic influence is responsible for the Spider-Man films’ recent success, we insist on a new deal. If you won’t budge on your position, then…we’ll drop Spider-Man from the Marvel Cinematic Universe AND we’ll stop providing creative direction for the character and storylines.”

Sony: “You wouldn’t dare!”

Disney: (gets up from the negotiating table and walks out).

Sony: “Fine! We don’t even need your help. We can make good Spider-Man movies all by ourselves. Plus, we have star Tom Holland under contract for two more movies.”

Now what? We’ve got a high-pressure game of chicken, with as much drama as anything in the pages of a comic book. As you would expect, both sides have used the media to portray the other studio as a super-villain.

Who stands to lose more?

With Spider-Man, Sony has a massive franchise on their hands — thanks largely to Disney’s shaping of the character over the last few years. Sony must believe that each of the next two Spider-Man films will generate global box office grosses around the $1 billion mark. Those predictions are probably right: although many fans have expressed sadness about Spider-Man’s departure from the Marvel Cinematic Universe, they will probably flock to the theatre to catch the latest adventures of one of the most popular superheroes, played by a charming young actor. For Sony, the prospect of handing Disney half of their billion-dollar box office haul must have been a complete non-starter.

In a perfect world, Disney would love to retain Spider-Man: the well-known character brings a sense of fun to the entire MCU. That said, the company wants to maximize profits. Disney recently reacquired the movie rights to some of Marvel’s most iconic comic book series: X-Men and Fantastic Four. Plus, Disney just announced an ambitious phase of new projects — 10 movies and television shows in 2020–2021 alone. Although the current deal with Sony spells out the financial terms, it doesn’t adequately address the contributions of Marvel President Kevin Feige, widely viewed as the person with the Midas touch, turning even obscure superheroes into box office gold. For Disney, there is clearly an opportunity cost to any time Feige spends on Spider-Man, instead of characters 100% owned by Marvel — a fact that’s especially important, because some of the new projects feature mostly unknown properties like the Eternals. In short, I am sure Disney believed the new proposal to Sony was more than “fair.”

Will either studio back down? And if so, who?

I expect someone will blink. A recent article in Variety reported a counter-offer from Sony: a 75/25 split for production costs and revenue sharing. If rumors of Disney’s previous demands of 30% prove true, then perhaps the sides are not that far apart.

The ultimate decision might not come from the studio’s top executives, but Kevin Feige himself. After building Disney’s most valuable new franchise, Feige probably wields the clout to tell Disney “I really want to keep Spider-Man, so please work with Sony to make it happen.” If, on the other hand, he says, “We have enough great characters to anchor the MCU, so we don’t need Spider-Man,” then you could expect Disney to hold their firm negotiating position.

Suppose Spider-Man ends up swinging solo for Sony. In the short term, not sharing the billion-dollar profits is likely the right choice for Sony. But what about the long term? That’s a far more interesting question, one that provides marketers with valuable lessons about branding, monetization, and more.

Remember, Disney built a 23-movie empire with very few characters that casual fans (i.e., people who don’t read comic books) could recognize. Somehow, the company managed to elevate B-list characters (like Iron Man), C-list characters (like Dr. Strange), and even D-list characters (like Groot) to prominent places in contemporary pop culture. In contrast, Warner Brothers struggled to gain traction for their “DC Extended Universe” with iconic heroes like Superman and Batman. Even worse, Universal absolutely flopped in their attempt to create a monster-centric “Dark Universe” with Dracula, Frankenstein, and the Mummy.

How did Marvel build a blueprint for success? Let’s take a look.

Marketing Lessons from the Avengers

Lesson 1: Structured Improvisation and Patience

In 2004, ABC premiered Lost, a television drama set on a mysterious island. The show’s combination of real-world action, mythological elements, and intricate mysteries kept viewers glued to their sets for six sprawling seasons. The intriguing twists, though, frequently painted the writers into a corner — some of their ideas injected great suspense into one episode, but disrupted the logical development of the show’s “big picture” story (see: clumsy justifications for the existence of polar bears in a tropical climate). Despite a legacy as one of television’s most innovative series, Lost is also remembered for some excruciating episodes and a series finale that disappointed most critics and fans.

For all six seasons, Lost drew reliably high ratings for ABC. With advance knowledge that Lost was winding down, the studio attempted to hold the attention of the show’s fans by launching FlashForward — another high-concept show that featured curious secrets. Brannon Braga and David Goyer aspired to create a show that avoided the sort of embarrassing turns and dangling mysteries that plagued Lost. With that goal in mind, the writers sketched out detailed narratives for the first FIVE seasons of the show. Alas, the over-prescriptive plans overwhelmed the series — the team focused on hitting specific plot points rather than allowing for the organic evolution of the show’s characters and style. Despite ABC’s hope in finding a ratings replacement for Lost, FlashForward’s viewership declined each episode and the show was cancelled after one season. No one got to see how the writers planned to solve all the mysteries by the end of season five.

Lost focused on the immediacy of each episode, at the cost of developing a coherent conclusion. FlashForward meticulously planned for the future, but dropped the ball on executing in the moment. All business endeavors, not just in the entertainment industry, face this tension — how do you balance careful plans for the future against the urgent actions for today?

When I speak to folks at early stage companies, many of them ask the same question: “how can we build systems that will be scalable when our company grows to a larger size?” These ambitious entrepreneurs overlook the inherent problem: if you are investing the majority of your time building your “perfect” long-term plans, then you are not spending enough time on the tasks that will keep you alive right NOW. If you won’t survive tomorrow, your plans for next year are irrelevant.

Marvel (and Disney) balanced this now-or-later question better than most companies. Kevin Feige joined Marvel late in production for their first theatrical release: 2008’s smash hit, Iron Man. Although Feige was not involved in the film’s conception, he was responsible for a brief scene during the end credits, in which Iron Man learns about the Avengers. Feige envisioned a “movie universe” where characters and stories would continue and connect. If stand-alone Thor and Captain America movies were as well received as Iron Man, then an Avengers movie could be produced (and that end credit scene would provide the foundation for the Marvel Cinematic Universe). If, however, the Thor and Captain America movies faltered, they could still proceed with the typical Hollywood formula — more sequels for projects, like Iron Man, that broke the box office (in that case, the end credit scene would STILL make sense, as a secret treat for die-hard comic book fans). Either way, Feige developed not only a dream scheme for the ideal future, but also viable contingency plans in case of any setbacks.

Let’s connect this idea to the recent Spider-Man negotiations. In interviews, Feige has explained that his team brainstorms the MCU’s major narrative arcs FIVE years in advance. That means Spider-Man factors into their plans until 2024 or so. Removing the webslinger from the MCU will probably require a substantial shuffling of their production schedule. But the Spidey stare-down isn’t Feige’s first (possible) disruption. A year ago, Disney was unclear if they could reacquire the rights to the X-Men and/or the Fantastic Four. A few years ago, Disney was unsure about their ability to re-sign Iron Man actor Robert Downey, Jr. for additional movies. No matter the obstacles, the beat goes on.

Without question, Kevin Feige demonstrates a prodigious mind that few of us can ever hope to rival. Still, every marketer and entrepreneur can learn from Feige’s formation of long-term plans (five years, in his case). More importantly, we should note that when Feige encounter challenges, he not only reacts to the immediate issue, but he also readjusts his long-term plans to reflect the new realities.

Lesson 2: Monetization

What brings in more money at the box office, “good” movies or “bad” ones? Perhaps surprisingly (or not), the correlation between box office success and film quality is not high. Drawing on box office information and scores from review site Rotten Tomatoes, Mac Woolf published a blog post that found the correlation was actually negative.

Whether fans like it or not, Hollywood studios are businesses that aim to maximize profits. So…if a movie’s quality does not impact its box office gross, then WHY would studios care what critics or audiences think about their films’ artistic merits? There are probably a few reasons. Here’s one: the end credits of any movie list the names of thousands of studio administrators, creative artists, technicians, and support services. All of those people would probably enjoy being associated with highly respected projects (see “Marketing to Employees”).

Nevertheless, studios are incentivized to make decisions that increase box office grosses, even at the expense of product quality. As such, many movies are terrible. The studios didn’t TRY to release a bad movie; they simply focused on decisions that would make the most money. Producing a “good” movie is just one factor for maximizing profit (and as the correlation chart shows, not a particularly important driver).

This reality mirrors the tendency of marketers to send lame sales-driven emails (see “Presidential Emails”). Messages with click-bait subject lines WILL drive more short-term revenue, but at the cost of damaging the long-term brand identity. The number one driver of email open rates is not the cleverness of that specific subject line, but the quality of the last 10 emails you sent to that person. If every email from Marketing BS brings you joy, then you’re likely to open the next one regardless of the subject line. Conversely, if every email contained a hollow sales pitch, you’ll only get tricked by sneaky subject lines so many times.

Let’s connect this “short-term gain brings long-term pain” concept to the movie industry. Most audience members cannot identify unique brand identities for Paramount Pictures, 20th Century Fox, Universal Pictures, Columbia Pictures, or Warner Bros (five of the six major Hollywood studios).

But all notions of brand ambiguity go out the window when you are building a franchise. In that case, brand quality matters.

Every studio cares about creating franchises (especially the conventional sequels for popular films), because they represent the surest path to financial success. Walt Disney Pictures (the other major studio) cares far more about franchises than their rivals; this is understandable, given that Disney is probably the only studio with a brand identity that can be recognized by the average moviegoer. When you go see a movie produced by Disney (or one of their subsidiaries: Pixar, Star Wars, or Marvel), you enter the theater with clear expectations about not only the style, but also the level of quality.

Disney’s significant investment in their brand has paid off in a number of ways, but it’s also required close control of their creative projects. Disney demonstrated a tolerance for risk by casting Robert Downey, Jr. (with a history of substance abuse and legal trouble) for the role of Iron Man; likewise, the studio took a stylistic leap by asking Kenneth Branagh to direct the Thor movie with a Shakespearean sensibility. Although Disney has encouraged artists to express their individual ideas, Kevin Feige has prevented anyone from coloring too far outside the lines; case in point, he fired Edgar Wright as the director of Ant-Man over “creative differences.”

Because Disney possesses such a strong brand, they are more concerned about the credibility of the entire Marvel Cinematic Universe than they are about the box office returns for any one specific film. Moreover, Disney can justify investments that improve the quality of a film, even at the cost of reduced profit.

Beyond the actual films, Disney can also monetize the properties in many other ways. Popular Disney characters can be found everywhere: lunch boxes, theme park attractions, action figures, ice shows, Broadway musicals, and Halloween costumes (of Walmart’s 10 best-selling costumes last year, nine were Disney characters). Perhaps ironically, the more ways you have to monetize, the less you should focus on short-term monetization (and the more you should care about quality).

Lesson 3: Brand consistency

New CMOs love making changes to brands, but that’s an easy way to destroy value. The best brands cement an identity over time and change very little, if at all. Remember: a brand is a promise to deliver a consistent result. Every time a brand changes, it messes with that promise, causing customers (both regular and potential) to rethink their expectations of the brand. I’m not suggesting that brands should never change; instead, I want to emphasize that that any change — even a positive one for the long term — carries a real short-term cost. As such, any CMO clamoring to change a brand should be very sure that the long-term payoff will justify the (significant) short-term cost.

When it comes to brand consistency, marketers face a catch-22. Before you can get someone to engage with your brand, you need to get their attention. And what’s the best way to capture attention? Do something new. But new is exactly what you don’t want to do if you want to maintain a consistent brand identity.

What’s the solution? Create strong brand elements, and then allow creative people to play within the guardrails of the brand “rules.”

Kevin Feige has perfected this concept for the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

All MCU movies share a consistent aesthetic style, with a bright, colorful palette (in contrast to the dark and gritty vibe of the Superman and Batman films). Even when the Marvel superheroes face danger, the movies still radiate a feeling of optimism. In short, the movies all feel like they belong to the same “world.”

That said, the 23 movies differentiate themselves in some distinctive ways. All of the movies cling to a cohesive “MCU-style Superhero” style, but they also borrow elements from different film genres. Here are a few examples:

Iron Man — Science Fiction

Thor — Mythology

Captain America: The First Avenger — War

Guardians of the Galaxy — Space Opera

Ant Man — Heist

Spider-Man — Romantic Comedy

Black Panther — Afrofuturism

My prediction: expect a MCU Western and a Romance sometime in the next ten years. She-Hulk may be a legal thriller. Ms. Marvel would be a good fit for a coming-of-age Drama.

Marketers for companies with strong brand identities can learn something from the MCU — ensure consistency by establishing the core “rules” of the brand, and then capture customer attention by experimenting with contemporary variations that stay within those rules.

Lesson 4: R&D

The Marvel Cinematic Universe is a media empire built upon famous comic book characters, and yet, comic books themselves do not make very much money. In 2018, total comic book sales from ALL publishers (of which Marvel is only a part) hit $1 billion — less than the global box office haul for many single films in the MCU. Once you factor in production costs, labor, distribution, and retail markup. I wouldn’t be shocked to learn that Disney makes zero money from its comic book sales. You can understand why Marvel was constantly flirting with bankruptcy during their years as an independent company…

While comic books don’t generate the same level of revenue as a movie, publishing a comic book costs a lot less than producing a movie. At present, Marvel publishes 37 different comic book titles per month. Think about the sheer quantity of story ideas developed by their teams of highly creative people each year. Comic books present an opportunity to not only test new stories and characters, but also to receive ongoing feedback from readers.

In essence, then, Disney can treat the Marvel comic books as the R&D department for their movies. Disney can experiment with a plethora of ideas, and then adapt the best of those market-tested storylines for the big screen (often with improvements learned from the criticism of the first execution).

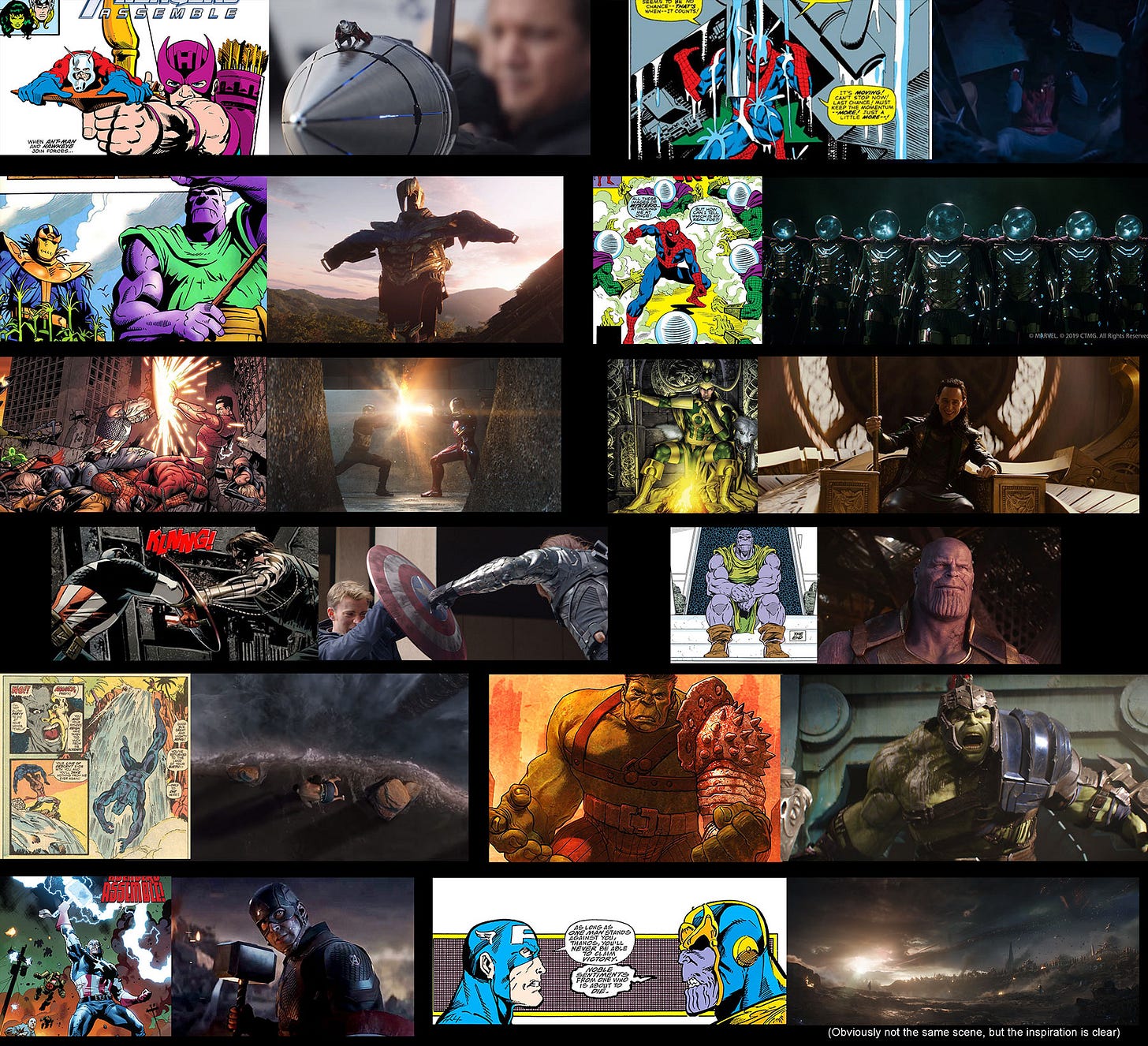

Before the Captain America: Civil War movie, there was a comic book series, “Marvel: Civil War.” Before the epic Avengers: Infinity War movie, Marvel ran the “Infinity Gauntlet” and “Infinity War” comic book miniseries. The storyline from the Ant-Man film borrows heavily from issue 47 of “Marvel Premiere.” MCU movies have even recreated specific panels from individual comics. Check out this fun collage (by dani2362) that matches scenes in the MCU films to the illustrations that inspired them:

Innovative companies need to find efficient methods for testing ideas and then scaling the most successful ones. Disney has institutionalized that process in a way that other film studios (and all companies, really) should envy.

Lesson 5: Focus on product features, not target audience

Here’s a brief section from my forthcoming book:

The most successful “environmental” cleaning brand of the last few decades is Method. Here's what their co-founder said when asked why it was so hard for them to get into Whole Foods:

We didn't wear the uniform of green. We wanted to change that. Those weren't the people we wanted. We wanted the people to buy our product who had never considered buying a green product. It's totally pointless to be making a green product for green people. Only about five percent of products on the US market sold are green products. If all you're doing is going and preaching to the converted and that five percent, then what are you doing? We want to make a product that appeals to everyone, not just the people who are going to shop on their environmental credentials.

Method treated “environmentalism” as a product feature, NOT as a target audience. If they had only pursued “environmentalists,” their brand would possess nowhere near the reach it does today.

Of the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s many successes, the pinnacle might be 2018’s Black Panther. The film received seven nominations at the Academy Awards, including Best Picture — the only such nomination for a MCU movie (or any superhero movie, actually). Moreover, with a $1.3 billion haul at the box office, Black Panther is the highest-grossing solo superhero movie in history.

With a celebration of African traditions and a creative team composed of African American artists, Black Panther appealed to African American audiences in unprecedented ways. According to Hollywood Reporter, 37% of Black Panther’s (North American) ticket buyers were African American, compared to the 15% mark for “typical” superhero blockbusters.

Of course, Black Panther is hardly the first film that appealed to African American audiences. But whereas projects like Tyler Perry’s Madea franchise focused on the African American community as a target audience, Disney created a movie showcasing African American artists and then highlighted that fact as a product feature.

Your target audience is only as small as your marketing department cares to imagine.

Based on the success of Black Panther, Disney recently announced new projects that celebrate specific cultural communities: Shang-Chi (a Chinese superhero) and Ms. Marvel (a teenage Muslim of Pakistani-American heritage). I expect Kevin Feige is combing through Marvel’s catalog, looking for more demographic groups to celebrate.

Another prediction: expect solo Latino, LGBTQ+ and religious MCU characters over the next decade.

Final Thoughts

In case it’s not painfully obvious, I grew up reading comic books and I love movies. But when I attended business school and embarked on a professional career, I expected that the best corporate practices would be found at the “serious” companies.

So, it’s with great pleasure that I’ve watched the Marvel Cinematic Universe emerge as one of the most impressive case studies from this millennium. I hope that marketers can see beyond the light-hearted spirit of the MCU, in order to appreciate some valuable lessons about flexible long-term planning, brand consistency, monetization, and more.

See you at the cinema!

Keep it simple,

Edward

If you enjoyed this post, I encourage you to click the little heart icon below my bio. Thanks!

Edward Nevraumont is a Senior Advisor with Warburg Pincus. The former CMO of General Assembly and A Place for Mom, Edward previously worked at Expedia and McKinsey & Company. For more information, including details about his latest book, check out Marketing BS.