Remote Work, Innovation and Getting Lucky

Some of the most impactful things are hard to measure

This summer my family is re-locating to an island in Greece. Travel starts this week. There may be a few weeks where I do not post four times, and this week is likely to be one of them. Clearly you are getting this post, and I will be sure to do one more for paying subscribers (likely published on Thursday or Friday). For everyone else, I will be back next week. Enjoy today’s post in the meantime.

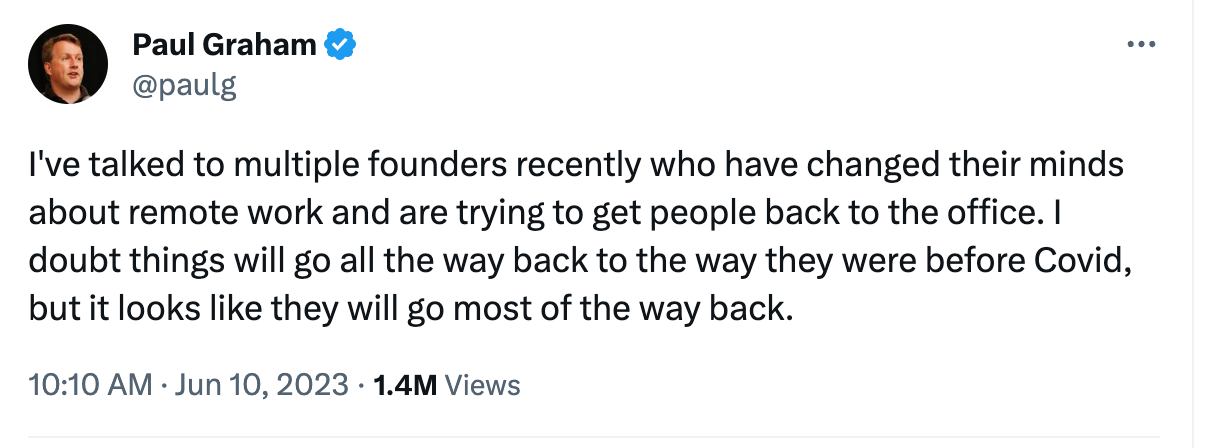

This past weekend Paul Graham, co-founder of Y Combinator and prolific writer of essays was tweeting about remote work (link here, screenshots due to Twitter blocking embeddings on Substack now):

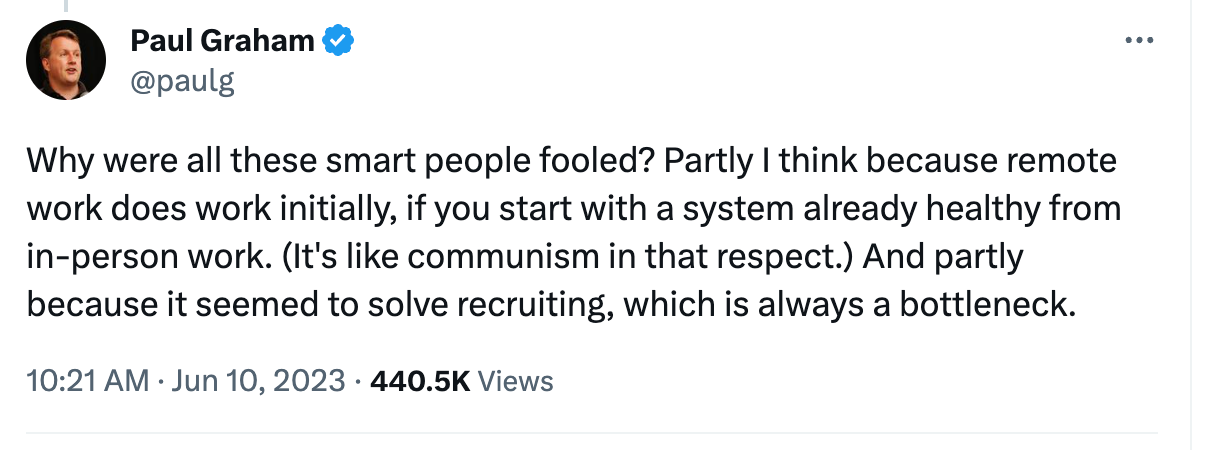

Full quote for those squinting on their phones:

I've talked to multiple founders recently who have changed their minds about remote work and are trying to get people back to the office. I doubt things will go all the way back to the way they were before Covid, but it looks like they will go most of the way back.

Why were all these smart people fooled? Partly I think because remote work does work initially, if you start with a system already healthy from in-person work. (It's like communism in that respect.) And partly because it seemed to solve recruiting, which is always a bottleneck.

There will definitely continue to be remote-first companies. There were before Covid. It works for some businesses. And there will be types of jobs, like customer service, that will commonly be done remotely. But remote-first won't be the default.

Summary:

Remote work can maintain things, but is not as good at building new things

It is a LOT easier to recruit if you offer remote work

Add to that (not stated by Graham):

Quantified measurement shows that remote workers are more productive than those in the office (HBR article from 2014)

The combination of the three bullets means that in the short term companies are better off by going remote. Measured productivity of employees goes up, recruitment of new employees gets easier (therefore less expensive, or higher quality for the same expense), and there are no obvious downsides.

But as is often the case, the short term metrics miss the longer term implications.

When I was at A Place For Mom sometime in 2012 I had a one-off conversation with a finance manager. In an off-hand comment he asked me why we haven’t raised prices. I hadn’t thought about it. 2012 was the hardest year of my professional career. We had added a large amount of expense to the business (executive compensation which for roles that did not exist before like “head of marketing”, “head of sales”, “head of recruiting”, “CTO”, and other somewhat essential roles), completely changed the compensation system of the salesforce, built a call center from scratch, and hired a celebrity spokesperson — among other things. We modeled that our revenue would take off in April and when it didn’t (it was flat for the full year) we found ourselves scrambling to make payroll. The last thing we were looking for was "another idea”. We just needed to keep our head above water.

But the conversation stayed with me.

In 2013, when the business DID begin to grow, I started working to convince my CEO and the board that we needed a price increase.

I know that the price increase would not have happened if I had not pushed for it to happen. It barely happened as it was (and the increase was only half as high as I was pushing for). And I am pretty sure I would not have decided to push for that price increase if not for that conversation with the finance manager in 2012.

If we had been working remotely in 2012 I do not think that conversation would have happened. No conversation, no push by Ed, no price increase.

The business would have done fine without the price increase, but with it, it changed everything. I believe it generated about $400MM in enterprise value. Executing the price increase was a gargantuan effort of a large number of very talented individuals. But that effort would not have happened if not for that conversation.

If we had been working remotely in 2012 we might have been more productive, and no metrics would have ever picked up the conversation that did not happen between a finance manager and the head of operations. We would have still turned the corner in early 2013, and we would have sold for a very solid return a few years later. The company would be declared a success, we would have decided that remote work was great, and no one would have known about the huge upside that did not happen.

At the beginning of every Marketing BS podcast I include audio of Jeff Bezos saying, “The thing I have noticed is when the anecdotes and the data disagree, the anecdotes are usually right. There's something wrong with the way you are measuring it.” This is another example. We KNOW that there is something about being in person that creates value in a different way than remote. We know that when we were new hires, (some of) the in-person mentoring we received made a huge difference later in our careers. We know that if you want to build a new relationship with someone, being in person allows that to happen in a way that talking on Zoom does not (salespeople fly out to meet you for a reason). But because we can’t quantify it, and because working from home is so much more convenient, we find a way to convince ourselves that remote work is the future.

Coincidentally last week, Tyler Cowen wrote an opinion in Bloomberg trying to explain the current financial metrics:

The paradox that currently defines the US and global economies goes something like this: If business is mediocre, why do firms keep hiring more workers? And if US workers are doing less, why do bosses want more of them? Measured growth is poor, yet the labor market continues to boom. There is also productivity crisis, at least according to the usual measurements, with year-to-year productivity growth negative for five consecutive quarters.

Summary:

Productivity of workers is down, but demand for workers remains high

We have slow (maybe negative) economic growth, but demand from consumers remains high (high inflation)

Cowen thinks he may have an explanation:

The productivity question is even more puzzling. If worker productivity is low, why keep on hiring? The key may be to look not at total productivity, but at productivity per hour — and not per reported hour, but per hour actually worked.

I concede that there exists no measure of productivity per hour actually worked. (The official number, which is not doing great either, measures productivity per reported hour.) But if the average office worker only puts in say two to three hours a day — and it is not implausible — then there is a lot of slack in the worker’s day, especially if they are WFH.

So consider this thought experiment as a possible explanation: You are a manager and have noticed that new hires tend to be more enthusiastic and hard-working than current employees. Under this theory — and that’s all it is — you decide to hire more contract workers for well-defined, short-run tasks. Meanwhile, you redouble your efforts to bring workers back into the office.

The current metrics aren’t cutting it, so Cowen is looking for new metrics. Meanwhile managers are ignoring the metrics, and trusting the anecdotes, and bringing people back into the office.

Keep it simple,

Edward

Ed-

As always, on point. The bottom line it is the Mehrabian rule in action. https://bit.ly/3N6d5FL. WIth well over half of all communication being non-verbal, there is no way ideas and new concepts can be conveyed in an efficient manner. In addition, momentum, energy and vibes - all felt in the presence of others, is hard to replicate virtually and is a skill in and of itself. Hence, remote managers need to understand that their role has also expanded if and only if they want to be successful. This includes using as many tools as possible to convey non-verbal communication.

So, the recluse employees with legions of cats that loathe human contact had their day in the sun (errr I mean their stage of empty solitude, extreme comfort and voluntary isolation) and it is time now for normalcy to resume.