Where Could This Go?

Welcome to Marketing BS, where I share a weekly article dismantling a little piece of the Marketing-Industrial Complex — and sometimes I offer simple ideas that actually work.

If you enjoy this article, I invite you to subscribe to Marketing BS — the weekly newsletters feature bonus content, including follow-ups from the previous week, commentary on topical marketing news, and information about unlisted career opportunities.

Thanks for reading and keep it simple,

Edward Nevraumont

Substack Takes Series A

On July 16, Substack revealed some big news (via their blog):

...we graduated from the winter 2018 batch of Y Combinator and subsequently raised $2.2 million in seed funding, we’ve spent the last year working out of Chris’s living room in San Francisco. Now it’s time to add some firepower.

Today, we’re announcing that we’ve raised $15.3 million in a Series A funding round led by venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, with participation from Y Combinator, an existing investor. Andreessen Horowitz’s Andrew Chen will join our board. [Emphasis mine]

So…what is Substack?

THIS is Substack. The newsletter you’re reading, I mean.

In simplest terms, Substack is a platform that allows writers to publish newsletters — like Marketing BS. On some level, adopting Substack has complicated my workflow. I already use (and pay for) the domain of my primary website, MarketingBS.com. Plus, I already use (and pay for) MailChimp to collect and manage email addresses. I would save time and money by sending these newsletters via my existing accounts.

In addition to the savings, NOT using Substack would offer some other advantages:

Messages would be sent from the marketingbs.com domain, which would create a more consistent (and professional) means of communication.

More sophisticated tracking tools (e.g., number of unique readers, monitoring social media activity, etc.).

Ability to personalize emails (e.g., sending modified messages to subscribers who are currently CMOs).

More control over the aesthetic style. (For instance, I can’t address a subscriber’s request to widen the columns of the newsletter for reading on a desktop).

Despite all those factors, I chose Substack? Why?

Let’s start with some quick context. In 2017, three entrepreneurs — Chris Best, Hamish McKenzie, and Jairaj Sethi — set up shop in San Francisco and launched Substack. The company not only simplifies the process of sending newsletters, but also specializes in helping writers move from FREE newsletters to PAID newsletters.

Pretty quickly, they struck gold:

…we watched in amazement as our first customer, Bill Bishop, publisher of Sinocism, brought in six figures of revenue on his first day with Substack for his previously free newsletter.

Since then, Substack has demonstrated that their model — upgrading subscribers from free newsletters to paid ones — is a feasible one for many writers. By Substack’s first anniversary, they had attracted 25,000 paying subscribers. Less than eight months later, they’ve reached 50,000. Substack allows writers to set their own subscription fees, with a minimum charge of $50/year. Quick math: 50,000 subscribers multiplied by $50 means that AT LEAST $2.5 million in annual subscription revenue flows through their system. The real figure is likely higher, as many writers — especially ones with specialized knowledge — charge around $100/year.

The Substack platform is staunchly opposed to ads; they generate revenue by taking a 10% cut of all subscription fees. With the current monetization model and the existing growth rate (not to mention the lean team of just the three founders), it shouldn’t take long for the trio to earn a dependable living — or a very comfortable one if the platform continues to scale.

Accepting $15.3 million from a Series A funding round changes everything. The three founders will face pressure to shoot for the moon, growing Substack into the next ‘unicorn’ (a private company valued at more than $1 billion).

Can anyone reasonably expect a platform for subscription newsletters to earn a valuation in the billions of dollars?

Ben Thompson doesn’t think so, and he has the experience to back up his opinions. In 2013, Thompson pioneered the “free once a week, pay to get more” model with his Stratechery newsletter. Here’s how he described Substack’s Series A round, in one of his daily (paid) letters:

Frankly, I’m a bit skeptical: while I am a huge believer in the possibility of individual writers building their own atomic publications, I’m still not certain the (necessary) role of being a Faceless Publisher is a venture-scale business… To be clear, I believe this business model works, and for more people than myself; however, is supporting people like me a $150 million business, which would give Andreessen Horowitz its 10x return? I’m not so sure… [Emphasis mine]

(Thompson also published a full length interview with Best and McKenzie, providing more context on the company and the investment).

Back to my earlier question: why did I choose Substack?

Marketing BS is free, and I will never charge for this newsletter. I really enjoy connecting with people to discuss the nuances of the marketing industry. But who knows — if enough people show interest in more frequent posts, perhaps I would explore adding a subscription level for those readers. And Substack would facilitate that process with far less complications than my own attempts to start from scratch.

Moreover, I genuinely believe that Substack has a real shot at becoming a billion-dollar company. In today’s newsletter, I’m going to outline how lessons from other industries might pave the way for Substack’s future success.

Where Could This Go?

Interesting subplot for Substack’s Series A funding round: Andrew Chen will sit on their board. After serving as head of growth for Uber from 2015–2018, Andrew developed a notable profile in the tech world and joined the team at Andreessen Horowitz. He also writes a popular newsletter…not yet on Substack.

What Uber-related insights might Chen share with Substack? Perhaps the stories of people who chose NOT to support Uber. In 2016, venture capitalist John Greathouse wrote a detailed post about why he did not invest:

The company began operations in San Francisco, a tech savvy city with notoriously terrible taxi service and a concentrated downtown. Additionally, Uber initially focused on replacing limo-style town cars and thus appealed to a relatively small number of upscale riders who have smartphones and no worries about price.

Although it was a brilliant market entry strategy, it contributed to my misunderstanding of the opportunity. I viewed their value proposition as a town car substitute, rather than appreciating the larger opportunity to eventually cannibalize the taxi market. [Emphasis mine]

Greathouse (and MANY others) passed on Uber because they didn’t believe town cars provided a big enough market. By now, of course, we see the bigger picture: town cars were Uber’s entry point into transportation, not the end point. (As for the early seed round investors who DID trust Uber — analysts estimate a return at just under 5000x).

Same story for Airbnb. The original concept explains the company’s name: a platform where people could charge guests to sleep on air mattresses. Even more so than Uber and town cars, the market size for people willing to sleep on air mattresses in strangers’ living rooms looked very, very small.

On the How I Built This podcast, Airbnb’s founders described the usual reaction to their product:

We go to the interview in the small tiny room at the [Y Combinator] office and there's four Partners around the table we sit down in the very first thing out of Paul [Graham]’s mouth is “How many people actually use this?” and “Oh yeah that's weird.”

After initially rejecting the pitch, Paul Graham changed his mind (he admired the founders’ tenacity to keep their company afloat by selling election-themed cereals: Obama O’s and Cap’n McCains). No one imagined that Airbnb posed a disruptive threat to Expedia and Booking.com. Still, Graham believed that the “weird” concept might have potential to pivot into a much larger business.

How can the histories of Uber and Airbnb inform our perceptions of Substack?

They provide clear reminders of the most important idea to consider when evaluating a company in the early stages: the potential of what they COULD do in the future, rather than what they are doing RIGHT NOW. Of course, attempts to predict the future often end in disaster (especially for VCs). Still, we need to stop asking “is this current thing big enough?” and start wondering, “where could this go?”

The Bullish Case for Substack

The need to look beyond the immediate is not lost on Ben Thompson. Later in his Stratechery letter, Thompson outlines a path for Substack’s success:

At a minimum, I do think that Substack will need to quickly expand their purview: I am not only bullish on individual writers, but also on the potential for local news. That, though, needs more expansive tools. Substack has committed to the venture course and will need to lean in heavily to owning the entire subscription space. [Emphasis mine]

For years, Thompson has proposed a way to fix local news operations: remove all ‘non-local’ info. Why should a Seattle journalist spend their limited resources covering an earthquake in Asia, especially with the ease of accessing stories from the Associated Press or Reuters?

In Seattle, Kevin Schofield provides daily coverage of local politics via his blog, Seattle City Council Insights. At the moment, Schofield monetizes his blog through Patreon, but there is no reason he couldn’t move to a paid newsletter, Substack-style.

In theory — and I acknowledge it’s a stretch — Substack COULD grow into a platform that disrupts the journalism industry.

Suppose Substack DOES manage to “own” the news — is that the absolute ceiling we can imagine for the company?

Privately owned newspapers don’t always share their readership numbers, but — because they are vehicles for advertising business — we can usually parse sources to derive reliable estimates.

For context, here’s a list of subscription estimates for some major English-speaking newspapers, counting ONLY the paid, digital versions:

The New York Times — 3 million (2018)

The Wall Street Journal — 1.5 million (2019)

The Washington Post — 1.27 million (2017)

The Guardian — 0.6 million (2017)

Regional papers in the US have struggled with subscription levels. Major outlets like The Los Angeles Times and The Boston Globe hover around 100,000 paid digital subscribers, while a local paper such as the Seattle Times boasts 36,000 digital subscribers.

How many subscribers would Substack need to achieve unicorn status?

For this hypothetical scenario, let’s suppose Substack maintains their current revenue model: taking 10% of subscription fees charged on their platform. When the company’s growth rate flattens, they’ll want to hit at least $100 million in EBITDA. The founders have demonstrated a keen ability to control costs, so let’s say they can reach that goal with $200 million in total revenue. Just to be clear, we’re talking about $2 billion in annual subscription spend on their platform!

That’s a lot of money.

But let’s provide some context. Substack sets a minimum subscription price of $50/year. Many of the “fun” newsletters (sports, science fiction, knitting, etc.) launch at the minimum price. Subscriptions that can be rationalized as a business expense, on the other hand, command higher fees, generally starting at $100/year (and going up from there: Messari, a newsletter about cryptocurrency, charges $75/month). If we assume the average subscription is $100/year, let’s think about what it would take for Substack to reach $2 billion in annual subscription spend: $2B / $100 = 20 million subscribers. Or, put another way, more than six times the subscriber base of The New York Times.

That’s a lot of people.

Of course, many people subscribe to more than one newsletter. But still — 20 million people is roughly three times the number of paid subscribers for the NYT, WSJ, Washington Post, and Guardian COMBINED.

You can understand Ben Thompson’s skepticism. For Substack to reach the top echelon of VC-backed companies, it would essentially need to overtake the major newspaper outlets — as well as the local news ones — and then some.

But looking at Substack through this lens is akin to estimating how many town cars Uber would need before going public. Disruptive journalism might provide a beginning for Substack, but I doubt that will be how their story ends.

So…what is the Substack equivalent of expanding into taxis?

Substack for Artists

Perhaps Uber and Airbnb aren’t the best role models for Substack (and not just because they’re billion dollar companies). Both Uber and Airbnb monetize a service, but Substack focuses on something entirely different: content creation. As such, I’d like to examine an industry — music — that might provide a more appropriate point of reference.

Let’s start with Danny Michel, a Canadian musician. Although he’s not a household name (even in Canada), Michel has carved out a stable career: releasing multiple albums, collaborating with acclaimed artists, and collecting a few awards along the way.

In November 2018, Michel’s comments about the economic realities of contemporary musicians were shared widely on social media. He outlines many ideas that might impact Substack’s future, so I’m including his entire post:

I’ve been a full-time musician for 25 years. It’s been nothing but hard work, but I love hard work. My songs bought my home, my studio, paid the bills and more. Through it all the conversations backstage with other musicians have always been about music, family, guitars, friends, art etc. But in 2018 that conversation changed. Everywhere I go musicians are quietly talking about one thing: how to survive. And I’ve never worried about it myself UNTIL 2018. What I can tell you is my album sales have held steady for the last decade until dropping by 95% this year due to music streaming services.

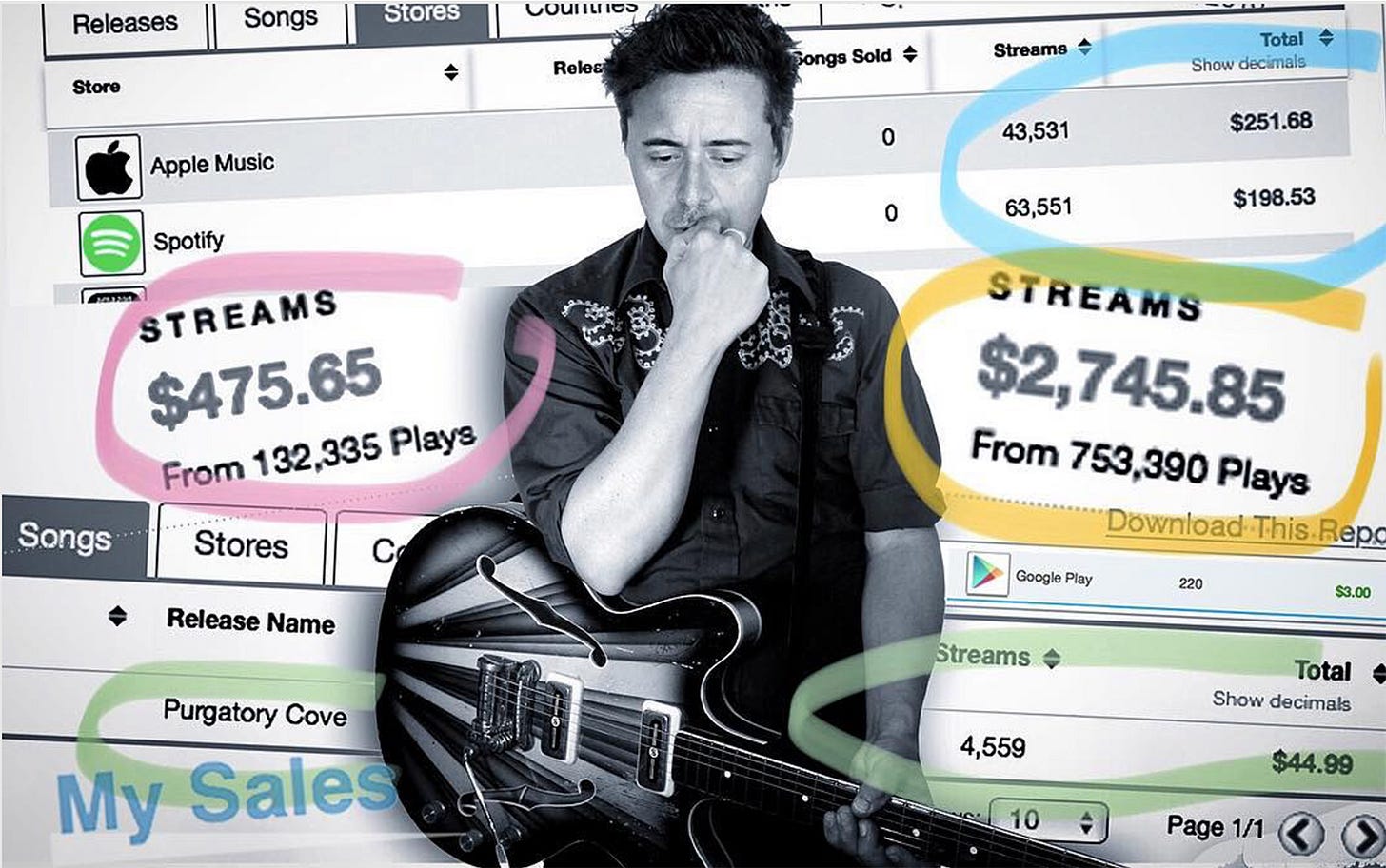

Note my earnings for “Purgatory Cove”: this song has been in the TOP 20 charts (CBC Radio 2 & 3) for 10 weeks, climbed to #3. In 2018 that equals $44.99 in sales.

I know I’m not alone. As a result bands/musicians are downsizing, recording at home, cutting corners wherever they can. Studios are losing business. Session musicians, techs, administration, grant writers are all losing work. And with every band in the world back on the road, venues are clogged and ticket prices have tripled. For me it means being away from home and taking on more work than I ever have.

A recent post by @unisonfund showed “In a study of the music industry labour market, 24% of musical professionals indicated they were considering leaving the music industry”. Having to be the constant used-car salesman, manager, admin person AND travelling artist (while in survival/panic mode) isn’t healthy. Yet, you can’t afford to hire anyone.

Social media makes it all worse and as a fellow musician pointed out, streaming services shame artists with the pressures of how many “likes,” “streams” and “followers” they have. No one needs to feel sorry for me. This is what I do. And I’m not scolding anyone or suggesting people stop using these services. I don’t know what the answer is. But I hope musicians speak up about what’s really happening. Music fans deserve to know how this all works and why the artists they love may soon be gone.

This new model of “free music” simply can’t last much longer. [Emphasis mine]

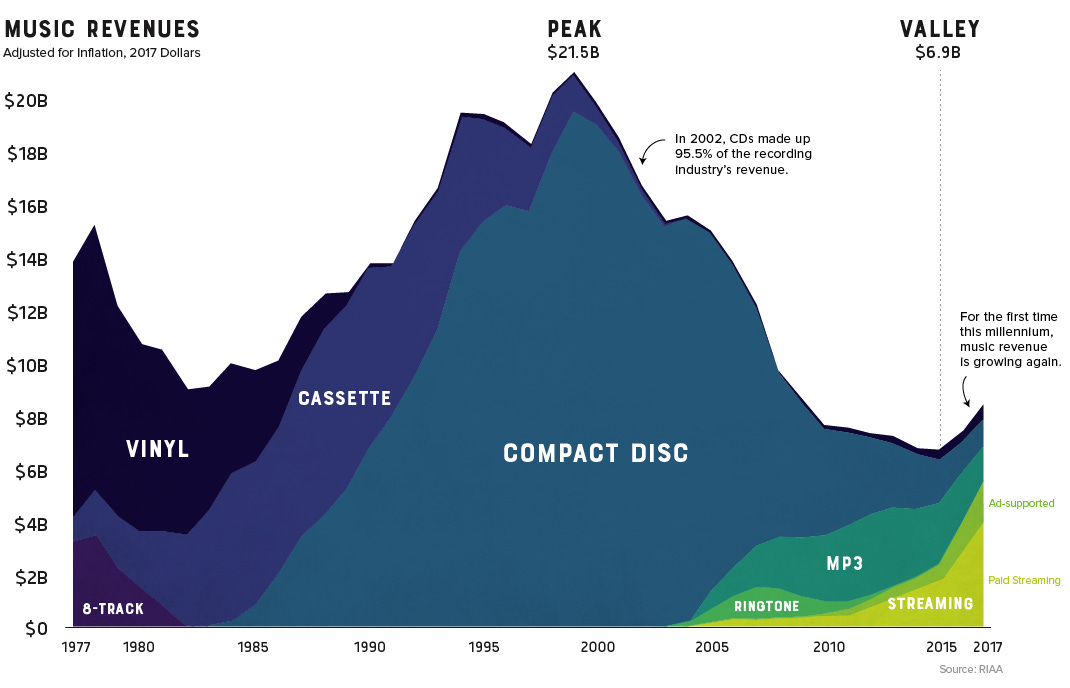

Despite Michel’s closing line, I don’t think the model of streaming music is going to end any time soon. Music industry revenue hit a low point in 2015, but has been rebounding over the last few years. Almost all of that growth can be attributed to streaming services. The Visual Capitalist published a chart that beautifully illustrates the last forty years of music revenue in America:

The chart ends with 2017, but the momentum has continued to trend upward; in fact, 2018 saw not only the best year for American music sales since 2005, but also the highest year-over-year growth rate every recorded. (Trends in the international music industry have mirrored the American ones).

So why does this rosy financial position contrast so sharply with Danny Michel’s growing economic precarity?

The answer, I believe, involves the NUMBER of fans versus the INTENSITY of fans.

In “How Brands Grow,” author Byron Sharpe presents the idea that ‘niche’ brands are a myth. Instead, loyalty to a brand (defined by share of purchases in a category for people who purchase the brand at least once) is highly correlated to market share of the brand. Backed by compelling evidence, Sharpe argues that market share and loyalty are the same thing. When brands use strategies to entice more consumers to buy their product, there’s a clear side effect: the tactics motivate their existing customers to buy their product more often. Distribution matters a lot.

A real-world example: I’d love to eat every lunch at Chipotle, but I don’t — because the restaurant doesn’t have a location near my home or office. Although I strongly prefer Chipotle over Safeway, my loyalty to Safeway is MUCH higher, because I live two blocks away from one. Coke understood this concept and did everything in their power to increase distribution, making their drinks available anywhere and anytime a customer might want one. What makes it easy for lots of people to buy a Coke also makes it easy for one person to buy Coke a lot.

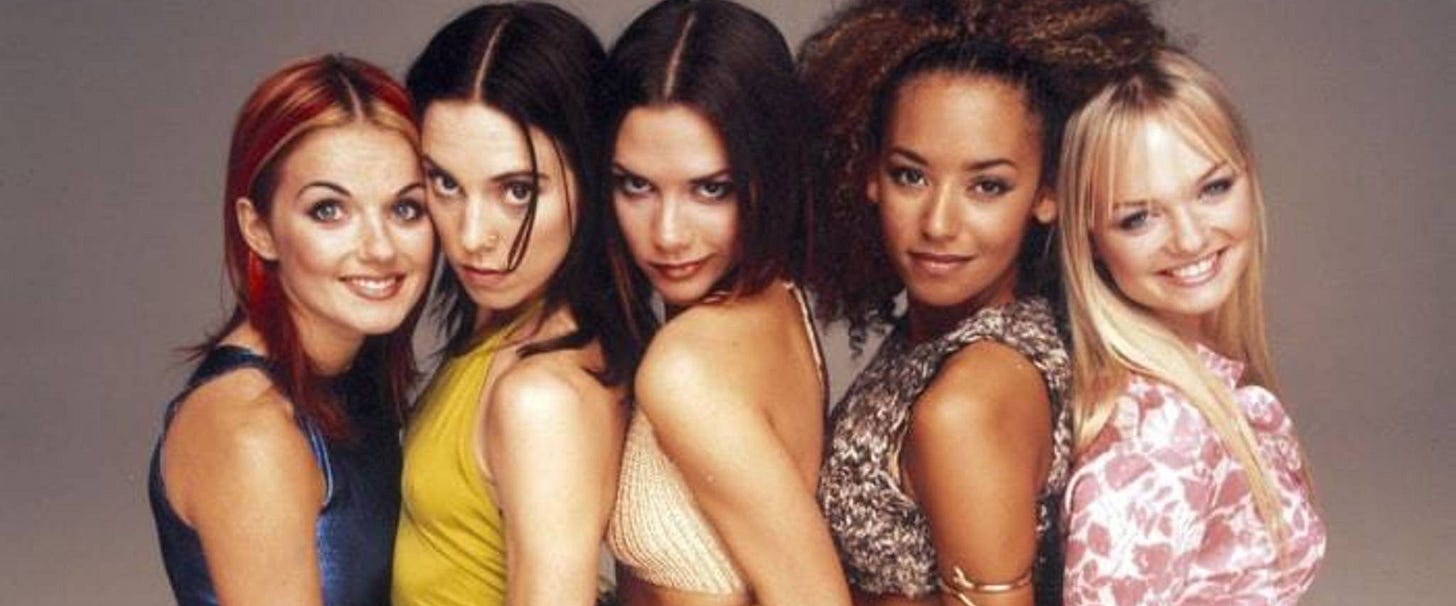

Music sales were no different. If someone purchased an album in 1997, there’s a good chance it was “Spice” — the debut release from the Spice Girls and the best-selling album that year (admit it, you own a copy…). A key point to consider: “Spice” was a popular choice among customers who regularly bought albums, but it was VERY popular among customers who bought ONLY ONE album that year. Why? Because market leaders dominate among customers who rarely shop the category. Popularity begets distribution which begets greater popularity which begets greater distribution…

Canadian musician Danny Michel also released an album in 1997 (by himself, without the support of a record label) — “Before The World Was Round.” I think we can safely assume that — in contrast to the consumers who purchased “Spice” — the vast majority of people who picked up a copy of “Before The World Was Round” were musicphiles who bought a LOT of albums that year. Moreover, among people who bought ONLY ONE album in 1997, I can’t imagine that a single person selected Michel’s album (unless that buyer was closely related to him).

Although Danny Michel has developed an audience of loyal supporters, many of those people could be described as music fans first and Danny Michel fans second. The Spice Girls, on the other hand, dominated sales charts by attracting not only passionate fanatics, but also people who rarely listened to music.

The NUMBER of fans versus the INTENSITY of fans

In the ‘CD era,’ musicians earned money from ‘intense fans’ — the ones who cared enough to buy an album or attend a concert. The ‘digital theft era’ changed the rate at which people bought music, but it didn’t change the fundamental calculus. Despite a loss in revenue due to illegal downloading, most musicians continued to earn the bulk of their money from their ‘intense fans.’

Streaming changed everything.

Now, for about $10 a month, music lovers can listen to (almost) any song they want. For most less-known musicians, though, streaming isn’t an ideal situation. Recording artists receive payment based on how many times someone streams their music; according to Digital Music News, Spotify currently pays out 0.437 cents for each play. By the end of the CD era, a fan could buy a physical copy of an album for about $20. For an artist to earn $20 via streaming, that same fan would need to listen to a song approximately 4,577 times!

To make matters even worse for indie artists, the streaming platforms provide additional advantages to the musical megastars:

The most-streamed songs appear on the best-selling charts (which are prominently displayed on the websites or apps).

Promotional campaigns usually highlight the new and upcoming releases from artists who have previously topped the charts.

When a listener streams a song, the algorithms recommend other (often more popular) artists within the same genre.

Let’s connect the music industry to Byron Sharpe’s assertion that market leaders dominate among customers who rarely shop the category. All of the above strategies lure casual music listeners into streaming the most popular artists, further entrenching the gap between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have no chance of living off 0.437 cents a play’ community.

What’s the solution? How do artists like Danny Michel survive?

Certainly not by asking fans to stream their songs a few more times each month.

If streaming platforms complicate indie artists’ ability to reach high NUMBERS of listeners, then perhaps there’s a model that restores the revenue potential from the INTENSITY of their fans. We shouldn’t expect consumers — not matter how passionate — to go back to the days of buying physical CDs. Why would they? Streaming platforms offer low-cost access to all of their favourite music.

If indie artists can’t sell CDs, what can they monetize?

Concerts? But as Danny Michel’s Instagram post stated, “with every band in the world back on the road, venues are clogged and ticket prices have tripled.” Plus, fan bases are spread around the world, limiting the capacity to scale.

What about T-shirts? Merchandise is a staple of the music industry, but any expansion would require greater attention to logistics, e-commerce, etc. (all things that would steal artists’ attention from creating and performing).

My suggestion: a musician could attempt Ben Thompson’s model for paid premium content. An artist could offer her or his fans some kind of ‘subscription’ for a fee — let’s say $50/year. What does subscription get you? Maybe a weekly email from the artist sharing their thoughts. Perhaps a weekly audio file of unreleased tracks that aren’t available on any streaming platform. Based on the astonishing sums that fans spend on concert tickets, I think you could find some people willing to pay $50/year to access exclusive content directly from the artists they love.

Why couldn’t Substack be the platform to support that model?

As demonstrated by the newsletters, Substack’s infrastructure already supports payment for subscriptions. Moreover, Substack allows publishers to send subscribers audio files (they’ve labelled them “podcasts,” but there's no reason they couldn’t be used for music tracks instead).

In the late 1990s, music revenues peaked above $20 billion. Illegal downloading, followed by streaming platforms, destabilized the industry. Even if the next innovation — artist subscriptions — only managed to capture a small corner of the action, there’s still potential for some significant revenue generation.

Not just Musicians

The sense of desperation conveyed by Danny Michel’s Instagram post isn’t limited to indie musicians. Artists from other disciplines encounter similar challenges in trying to monetize their work in a marketplace that favors the famous.

Substack could easily accommodate authors. How many people would subscribe to read a weekly short story from “Game of Thrones” writer George RR Martin? Verisart allows visual artists to release digital images that are “numbered” through the use of blockchain — would fans subscribe to an artist who sends limited edition digital prints every week? With the growing popularity of 3D printers, perhaps some innovative sculptors could offer a paid subscription model that shares plans for print-at-home works of art?

Substack could dominate the “artist subscription” model, but why stop there? They could drop the premodifier and become THE platform for subscriptions (Blue Apron via Substack?). Okay, so I don’t see the company growing in all of those directions, but I certainly never predicted that Uber would help manage public transportation systems, nor did I foresee Priceline’s (failed) attempt to use its reverse auction platform to sell gasoline and groceries.

Losing the Whales

Back to Ben Thompson and his interview with the Substack founders:

Here’s the concern I have, and I’ll be honest, maybe what stopped me from building this company is the fact that I was coming from the perspective of a content creator, and my concern was that once you reach a certain scale, how do you not lose people off the top? Suppose you get lots of people that want to try this model, and a lot of those people are going to fail, that’s sort of intrinsic in the idea, but you’ll make all your money off the superstars that really succeed. But how do you ensure that you don’t lose those superstars out the top end where they just go and build their own solution? What’s your lock in on writers, because at the end of the day, the whole idea of your company is that it’s these atomic individuals, to use my term, that drive all the value for these publications, and it follows that they are the people that are going to drive all the value for Substack. How do you keep those people on your platform in the long-run such that you’re achieving the return that you need? [Emphasis mine]

In his follow-up, Thompson builds on this idea of “losing the superstars”:

...any moves to maximize Substack’s revenue run the risk of losing its most profitable publishers out the top. I do think it is a reasonable bet by Andreessen Horowitz, but then again, their default position is that most of their investments will not generate that 10x return. [Emphasis mine]

Thompson’s worry is clear: Substack offers significant value for new writers, but any of their most successful writers could go out and build the infrastructure themselves. If you have 100 subscribers and earn $5,000 a year, you’re content to let Substack take care of web hosting, transaction processing, etc. But if you have 30,000 subscribers and clear $3 million a year — including a $300,000 annual payment to Substack —maybe you start to think, “I can build Substack’s infrastructure on my own for less than $300K a year.”

In essence, Substack overcharges their whales to subsidize their novices. The model works great for Substack’s continued success — they need to nurture the development of new writers into future stars. Of course, the structure is decidedly less great for the whales — what if they get tired of subsidizing the company and leave?

The concern is valid. For a good parallel, let’s look at digital marketing agencies. Most agencies tend to serve mid-market companies; once a client reaches a certain size, they often move their digital marketing in-house. If you spend $2 million a year on digital marketing, you can rationalize paying your agency $200,000 — you couldn’t even hire two people internally for that sum. But if you’re spending $20+ million a year, you could build a strong in-house marketing team for the $1.5 million (or so) that you would’ve budgeted for an external agency.

So…suppose you wanted to launch a paid newsletter. Should you start with Substack and — when you achieve success — break out on your own?

Ben Thompson, as one of the few people who transitioned from ‘regular blogger’ to ‘subscription titan,’ speaks from experience when he identifies Substack’s risk of losing their most popular writers. You can imagine Thompson looking at his own thriving business and thinking, “Wow. Substack would have been great when I was starting out, but there’s no way I would move onto their platform and pay them 10% of my income now!”

My suggestion for Substack: to avoid the fate of digital marketing agencies, focus on strategies that incentivize high-performing writers to stick with your platform. I can’t imagine that Ben Thompson would sacrifice 10% of his income to Substack, but perhaps he would consider 5%. What about 2%? Substack hasn’t announced plans to budge on their 10% share, but would they for Ben…

Alternatively, what if Substack remained firm on their fee structure, but implemented ways to make the platform as valuable as possible for star writers like Thompson. One way: reduce the hassles that burden writers. Substack could manage financial matters, site maintenance, and all the other non-writing stuff that Thompson (or his team) needs to juggle. Of course, there’s a structural flaw with this plan: operational costs don’t usually scale with revenue. If Thompson doubles his subscribers, you wouldn’t expect his accounting and web hosting costs to double. If your company takes a percentage of revenue for operational services, you will always undercharge the bottom and overcharge your top performers.

There’s another, more lucrative way to recruit and retain popular writers: increase the revenue steam. Suppose that by joining Substack, Thompson gained 10% more subscribers every year. In that case, paying Substack 10% of his income would be a no-brainer. Bolstering revenue seems like an attainable goal. For instance, Expedia can use marketing tools to analyze web traffic from travelers looking for hotels, and then guide those prospective customers to a perfect match. Substack could follow a similar approach by analyzing the online activity from people who might be interested in subscribing to a newsletter (or more than one), and then directing them to an appropriate writer.

And Substack has an advantage; unlike Expedia (and similar companies), the writers on Substack have zero marginal costs. Whenever a new person subscribes to a paid newsletter, the writer increases their profit by the same amount as their revenue. Every single dollar that someone pays them (less Substack and credit card fees) goes directly into their bank account. So, what should a writer be willing to pay for a truly incremental paid subscriber? Definitely more than 10% of whatever an annual subscription to the newsletter costs. I would actually advocate paying AT LEAST 100% of the cost for an annual subscription.

Why 100%?

Adding a new paid subscription doesn’t cost the writer anything; however, extra subscribers provide a bunch of things beyond the direct revenue:

Another reader — a paying reader at that! I imagine that virtually all writers LIKE when people read their work.

Many (most?) readers will renew in a year. As such, the lifetime value of a paid subscriber is FAR greater than the cost of their first year’s access.

Some readers will tell their friends. You’ll benefit from your newsletter’s ‘viral coefficient’ — the number of new readers generated by your existing subscription base.

Without question, any product that catalyzes subscriber growth should appeal to Substack’s writers.

Once again, let’s ask, “where could this go?” Could a ‘subscription engine’ be the feature that propels Substack to unicorn status?

The final section of this post, along with the career opportunities, appears in Part II of today’s newsletter.

-Edward

If you enjoyed this post, I encourage you to click the little heart icon below my bio. Thanks!

Edward Nevraumont is a Senior Advisor with Warburg Pincus. The former CMO of General Assembly and A Place for Mom, Edward previously worked at Expedia and McKinsey & Company. For more information, including details about his latest book, check out Marketing BS.