My plan this week was to move to a Tuesday/Thursday schedule for posting (free on Tuesday, paying subscribers on Thursday). That was thrown for a loop when I picked up a throat infection and a 103-degree fever (Do you know you are supposed to go to the ER if your fever is above 103? But what if it is 102.9? I stayed home, but it sure wasn’t pleasant!). I’m feeling much better now, very thankful for antibiotics, and hope to slide the second post out by tomorrow.

Last week’s post on the innovation cost of working from home caused a bit of an uproar. I think I hit a sore spot for some of you (who like working at home!). I am planning to loop back on that topic next week, including covering some of the objections I heard from you. It’s an important topic that deserves more coverage. But the paper I want to discuss today (and tomorrow) is also very important, and sits at the heart of the Marketing BS thesis that “when the data and the anecdotes disagree, there may be a problem with how you are measuring it”. Let’s dive in and hopefully I will be back on the regular schedule next week!

On July 24th Chetty, Deming and Friedman (Harvard, Harvard and Brown, hereafter the CDF study) released what I think is an incredible paper on “The Determinants and Causal Effects of Admissions to Highly Selective Colleges”. Raj Chetty’s research has come up before here at Marketing BS. He looked at the impact of families moving from “bad” zip codes to “good” zip codes on the adult financial situation of siblings who were a little older or younger (and therefore had a little more or less time in the good zip codes). More on that book review here and here. His earlier study showed that parental choices DO matter in raising your kids (if only in where you decide to live), contradicting earlier studies that claimed the reverse. He was able to show that because he had individual level tax return data from every American, and used it to find insights that earlier, less robust datasets missed.

This new paper does something very similar.

In order to write this paper CDF combined Chetty’s access to individual tax returns of parents and students with:

College attendance information from the Department of Education

Data from the College Board and ACT on standardized test scores

Application and admissions records from several highly selective public and private colleges covering 2.4 million students

In their words:

This dataset provides longitudinal information on a rich set of pre-college characteristics (parental income, students’ SAT and ACT scores, high school grades, academic and nonacademic credentials) as well as post-college outcomes (earnings, employers, occupations, graduate school attendance). Within this dataset, we focus on the 12 Ivy-Plus colleges, 12 other highly selective private colleges (e.g., Northwestern University and Washington University), and 9 highly selective state flagship public institutions (e.g., University of California Berkeley and University of Michigan Ann Arbor). We focus primarily on the entering classes of 2010-15, who are just old enough to observe post-college outcomes in currently available tax records

Never before has anyone been able to do an analysis like this one.

Prior to this study, the most cited papers have claimed that going to a prestigious college does not impact future earnings — that the increased income we see is all due to selection effect (Harvard admits really smart people and really smart people do well, whether or not they go to Harvard. When they do well after going to Harvard Harvard takes credit, but they would have done equally well going someplace else). They did this by looking at applicants who were accepted and then chose to go somewhere else. Those individuals (the control group) seem to do just as well on average as the candidates who choose to go to the school (2002 study, 2021 follow-up). The new CDF study finds that the earlier papers were wrong, mostly because they were underpowered. It turns out that going to an elite collage DOES make a difference and it is NOT just selection effect.

But the study is not just about the impact of going to a highly selective school. Even if you have never read an academic paper before, if you are at all interested in this topic I recommend you take a look at this one (here is the link again), or if you want to save time, just skip to the charts and data tables at the end (pages 65-126!). So much good stuff.

I am clearly not the only one excited by the study. Here is some of the coverage over the last week and a half:

New York Times:

Behind the Scenes of College Admissions (Jul 24th)

Study of Elite College Admissions Data Suggests Being Very Rich Is Its Own Qualification (Jul 24)

The Real College Admissions Scandal (Jul 26)

WSJ:

Washington Post:

America needs to stop relying on the choices made by elite colleges (Jul 30)

Junking Harvard’s Legacy Admissions Would Be Just a Baby Step (Aug 2)

The Economist:

Other Reading:

Marginal Revolution: The Causal Effects of Admission to Highly Selective Private Colleges (Jul 25)

Slow Boring: Harvard will never be an engine of social mobility (Jul 31)

An even better alternative that working your way through all of that opinion is to read a summary of the paper from one of the authors (on his new Substack):

Forked Lightning:

Welcome to Forked Lightning (Introduction to the paper, what data they had, and key takeaways on (1) why there are so many rich kids at elite colleges, (2) what is the impact of going to a highly selective college)

Ivy-Plus colleges are a gateway to the elite (Who and how one benefits from attending an elite college)

The lottery for high-paying jobs after college (How attendance at an elite college increases your chances to obtain an extreme right tail career event)

The trouble with holistic admissions (Non-academic factors are not predictive of future success (but academic factors are))

The Future of Highly Selective College Admissions (Why ending legacy admissions would not change very much, his personal recommendations — lotteries and increasing the size of the schools)

That’s a lot of content! I could stop here and treat this as a curation for you, my reader. But that’s not my style. I want to give two semi-contrarian takes over the next two days that I think even the study’s author missed. Today on the impact of attending an Ivy+ school, and tomorrow (for paid subscribers) on how the schools are selecting students (and why I think the “preference for rich kids because they are rich” is not what is happening, contra the NYTs).

Why Going to an Ivy+ School Accelerates your Career

In order to figure out the value of an Ivy+ degree, the authors looked at the waitlist. From Forked Lightning:

The Ivy-Plus colleges in our sample do not rank their waitlist, but all the applicants on it look roughly equally qualified. Still, only about 3 percent of the waitlist are eventually admitted. Are the admits [off the waitlist] more qualified than the rejects? No, at least not on any of the dozens of academic attributes we observe in the data. We verify this directly by showing that admission off the waitlist at one college does not predict admission at other colleges (we refer to this in the paper as the “multiple rater test”).

More pointedly, waitlist rejects from one school are just as likely to get into another school as waitlist admits, and much less likely to get in than regular admits.

What is going on? Our sense from the data, from other case studies of elite college admissions, and from talking to admissions officers at length is that admission off the waitlist is mostly about class-balancing and (to some degree) yield management. Colleges want a class that is broadly representative along many different dimensions, and if certain admits turn them down, they will look for others on the waitlist with similar characteristics (playing a certain instrument or sport, being from a particular state, etc.)

Since getting in (or not) off the waitlist is effectively random, the authors can look at the relative success of waitlisted candidates who got into Ivy+ programs vs those that did not (control). Since both groups are equally qualifies, they don’t need to worry about selection effects.

The results:

The three bars for baseline students who attended a “flagship public school”, waitlist rejects who attend a flagship public school, and waitlist acceptances who attend an Ivy+ school. Note that the waitlist rejects still outperform their new peers at the public schools, but the waitlist acceptances dramatically outperform the rejects. Now also notice the ways in which they outperform:

There is a small improvement in average earnings: 81.5-percentile to 79.3-percentile

There is a much larger lift in the percent that are top 1% in income: 19.5% to 12.4%

And even larger lifts in other metrics: chance of attending an elite grad school, chance of working at an elite or prestigious firm

The final caveat is that the oldest alumni in the study were only ~33 years old — so these are all early career metrics.

The authors conclude that while going to a Ivy+ school only raises your expected income a small amount, it gives you significantly more “lottery tickets” to make it into the top-1%. Here is how David Deming (co-author) puts it:

Think of it like winning the lottery. Suppose I told you and 9 of your closest friends that one of your group of 10 was going to win a prize - let’s say $1 million. But I don’t divide the tickets evenly. Since you attended an Ivy-Plus college, you get 2 tickets. Friends who attended a selective public university get one ticket, and those who didn’t go to college get none. Your odds are double anyone else’s, but you still probably won’t win. I increased your expected earnings. Going to an Ivy-Plus college gives you more chances to hit the jackpot. But among non-jackpot winners, things look pretty similar regardless of where you went to college.

Deming’s theory is that this happens because Ivy+ students are more likely to get jobs at highly prestigious firms, and than working for those firms gives employees a better chance of making it into the top 1% later in life. He goes further and argues the reason Ivy+ students are able to get jobs at the prestigious firms is because the firms themselves focus on the Ivy+ schools in their campus recruiting. He accepts that “social ties” developed at the schools may matter as well, but thinks they are not the true driver.

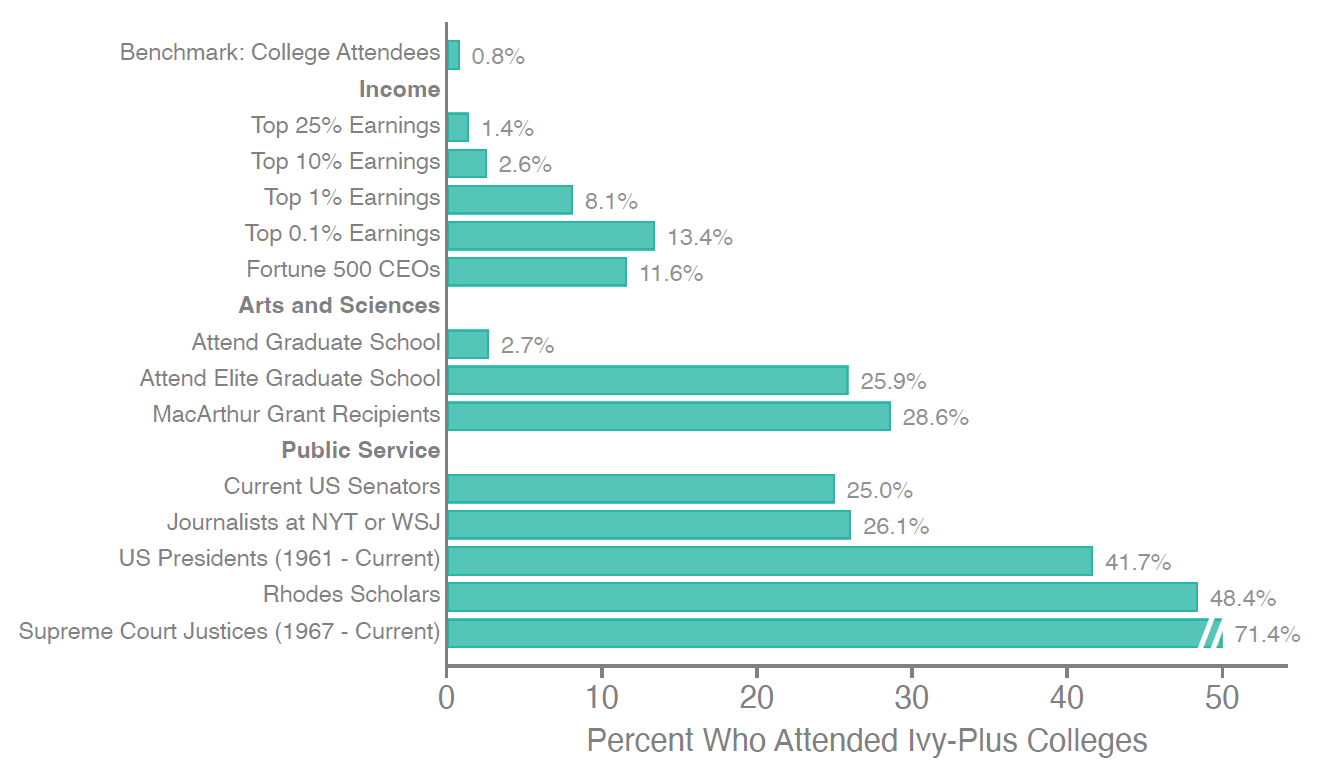

This chart is compelling (not corrected for selection effect):

Less than 1% of high school graduates attend an Ivy+ school, but Ivy+ graduates dominate the elite in our society. Even roles like CEOs of Fortune 500 companies, where almost 90% did NOT attend an Ivy+ school, are still over-represented by 10x.

I agree with Denning’s assessment that recruiting matters, and that going to a top firm (or top grad school) is one of the first steps on the path to being super-elite, but I think he under-appreciates the social ties, and how the social ties and recruiting build on one another. Especially as one moves further and further into one’s career.

(If you have not read my career guide, now might be a good time. I walk through how the path works. You don’t need to go to an Ivy to make it work, but it sure helps!)

Who you know matters

When I was a senior in college I was a Physics major who had no idea what I was going to do when I graduated. My roommate was in Commerce. He asked me if I wanted to go to a career info session. The sessions were a chance for companies to pitch to students, but more importantly included free food and beer. At the time I was budgeting $1/dat for my dinners (mostly bagels and peanut butter). The info session sounded like an improvement.

So having top firms recruit at my school (definitely NOT an Ivy+, but a good school for Canada) made a big difference. But what also made a difference was having a roommate and close friend suggest I attend. There is no way I would have gone to one of those things without him, and without that push I would have been unlikely to end up at P&G and who knows where my career would have gone (my guesses: a low-paid job doing advanced operations prep for Up With People, HR for Bombardier, or high school teacher).

That impact from peers only became more important as I got older.

When I left business school I worked for McKinsey. If I had gone to a less prestigious business school I think I would have still ended up there (McKinsey recruits at almost all the mid-tier MBAs, and does their best to hire the best in each region. Instead of being one of 80 hired out of Wharton I would expect I would have been one of two hired out of University of Western Ontario). From McKinsey I ended up at Expedia through a recruiter. No one cared where I went to business school or undergrad at that point. But my next company switch was different.

In 2011 a good friend from Wharton was visiting me in Seattle. He was looking for a CEO for a company his private equity firm had just acquired. I helped him recruit my boss at Expedia (who they never would have found otherwise), and I joined my boss at that company. Around the same time I invested in the company of another friend from Wharton. Then four years later another buddy from business school, who was now a partner at a venture capital firm, asked if I would help out one of his portfolio companies. I did and ended up joining that company as CMO/CRO.

Those three events are responsible for 90% of the wealth I have accumulated in my life. If they had not happened I expect I would still be doing very well (Wharton→ McKinsey → Expedia executive is a pretty good starting path for whatever would come next), but it is extremely unlikely I would be where I am today.

Did Wharton give my more lottery tickets for getting a job at McKinsey? Possibly. But the real value of Wharton were those three friends I made and how they helped me advance my career 6-10 years after I graduated — well into my late thirties and far beyond the time period that CDF are able to examine.

This is sometimes referred to as the “old boys club”, but I don’t think of it that way. This was not my getting ahead by utilizing the “alumni network”, this was friends asking me for help, and my having the right skills to be able to help them. And in all three cases I did. They could be telling the same story from the opposite point of view. Without me my first friend struggles to get a CEO for the business (and the rest of the exec team). The company likely fails (as it did when a new management team took over years later), and since he led the acquisition, it may even cut short his career at that PE firm. My friend who needed the investment was at the end of his rope. If he didn’t get the money from me when he did, his start up likely shuts down. My third friend’s VC investment also relies on my being there to help. Are there other people who could have done it? Absolutely. Could he find them in time for the crisis he was dealing with? Maybe?

By connecting a large number of smart people together, they build their awareness of one another, and their trust in one another. Being smart, driven and successful, and being close friends who are the same, results in oversized returns.

Turns out the real benefit of going to an Ivy+ school is the friends you meet along the way.

Turn in tomorrow for why it’s not all about the rich buying their way in.

Keep it simple,

Edward