Marketing BS: Downside of Convenience and "Nudging"

Good morning,

In this week’s podcast, you can hear part 2 of my interview with Joshua Kanter. We dig deep into his time as CMO of PetSmart.

—Edward

Convenience

I’ve regularly shared my opinion that convenience is underrated. Most customers don’t care about your product or service — so trying to “delight” them is usually less impactful than just making the purchase process easier for people. For instance, getting a Coke within arm’s reach of customers will sell more product than almost any other promotional strategy that Coke might try.

But…

I think it’s always worth considering the “steel man arguments” for your beliefs. In this case, what are the arguments AGAINST convenience?

Creating a Market for Avocados

There are some potential customers out there for whom your product meets their needs “to a tee.” These customers are your best customers — they are your “superfans” (an idea I wrote about last summer). Superfans will go out of their way and jump through any hoops to access what you are selling. While these devoted people would prefer a more convenient purchase process, they will not let inconvenience stop them from buying your product.

As you increase convenience, your superfans will likely purchase even more of your product. But, the real opportunity comes from expanding your market to people who do NOT possess the same fanaticism as your original customers.

Let’s think about this idea with a real-world example: guacamole.

A few decades ago, mainstream grocery stores in America rarely stocked avocados, let alone guacamole. Of course, there were always people (particularly of Mexican heritage) who regularly enjoyed guacamole; these superfans went out of their way to find avocados, which probably required trips to specialty food stores.

Over time, Americans became more familiar with avocados and guacamole (an ad campaign for the 1992 Super Bowl played an important role). As guacamole became more readily available in regular grocery stores — in other words, when the convenience increased — more people bought the product.

But still, many people were turned off from buying guacamole for a simple reason: if you didn’t eat the entire package, the leftovers quickly faded to an unappealing shade of brown. Companies have launched new package options for guacamole that have solved the problem of rapid browning — things like single-serving containers and squeezable bottles.

The increase in convenience has GREATLY expanded the market for guacamole. Total per capita consumption of avocados in America has tripled from 2001 to 2018.

Greater convenience increased the number of customers, but these customers were not all the same. The original customers represented a different demographic and (more importantly) exhibited different behavior than the new buyers who required a squeezable bottle before they would buy guacamole.

The differences between these groups are pretty obvious (spanning cultural heritage and social status). But for almost every product, this principle holds true. Each marginal increase in convenience brings you a marginally different customer.

Why does this matter?

Each new marginal customer is, almost by definition, marginally less interested in what you are selling. As a result, all the downstream metrics you were using for your earlier cohort of customers are (likely) to be marginally worse for the new customers you are bringing in the door. Back to our example: maybe the customers you acquired at the specialty store would have purchased guacamole thirty times per year, and perhaps 50% of that group also bought your co-branded products like salsa and tortillas. The new, incremental customers you acquired via products like the squeezable bottle of guacamole will probably make purchases at much lower frequency; plus, they are far less likely to add your brand of salsa to their shopping carts.

Nudging

In 2008, University of Chicago economist Richard Thaler and Harvard Law School professor Cass Sunstein released Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness.The best-selling book influenced everything from online marketing to school cafeterias to the British Government (The “Nudge Unit”).

Thaler and Sunstein articulated a strategy for guiding people to take certain actions:

A nudge, as we will use the term, is any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives. To count as a mere nudge, the intervention must be easy and cheap to avoid.

Rather than forcing people to make certain decisions, you should design choices so that the “low-friction” option is the one you want people to take. The most commonly cited example from the book relates to company-sponsored retirement savings plans. Most of these plans are based on employee contributions to a retirement fund — usually with some level of matching from the employer. Companies have two main options when presenting retirement savings plans to employees:

Provide instructions for opting into the retirement plan (usually when the employee first joins the company).

Automatically enrol the employee in the plan (but provide instructions for opting out).

In both cases, the process is nearly identical: an employee reads a description of the company’s retirement plan and then decides between “doing nothing” (accepting the default option) or “taking action” to indicate a preference for the non-default option. The process of “taking action” can be as simple as checking a box. And yet, even that tiny amount of friction can significantly shape people’s behavior.

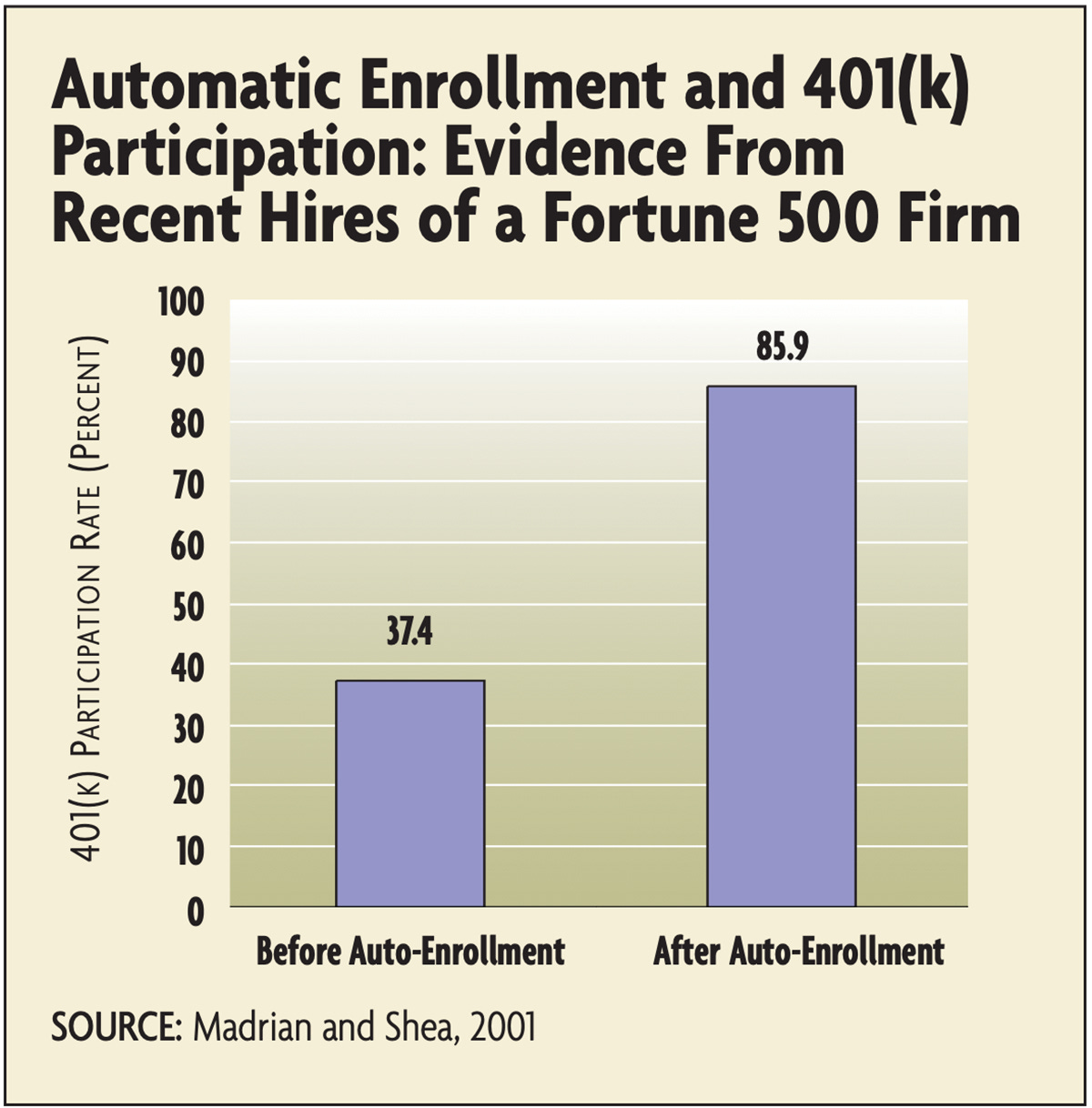

One study found that moving from an opt-in default to an opt-out one increased retirement plan participation among new employees from 37% to 86%.

These numbers seem to suggest that we can solve the “Americans are not saving enough for their retirement” problem by simply changing the pre-checked boxes on new employee onboarding forms. But in some ways, this idea was too good to be true.

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) has written about the long-term outcomes of opt-in versus opt-out plans:

While automatic enrollment encourages 401(k) participation, it anchors participants at a low savings rate and in a conservative investment vehicle. Higher participation rates promote wealth accumulation but the low default savings rate and the conservative default investment fund may actually lower employee wealth accumulation over a long period. In their investigation of the employees in the three companies studied, the NBER researchers find that the two effects are roughly offsetting on average. Although automatic enrollment has little impact on average long-run wealth accumulation, it does reduce the overall variance in wealth accumulation across employees. This is in part because automatic enrollment increases 401(k) participation among lower-paid employees and in part because some employees who would have participated in the plan without automatic enrollment do not bother to select an alternative to the automatic enrollment defaults and thus have a lower contribution rate and a lower return asset allocation than they would otherwise have.

NBER’s research conclusions are more impactful than I would have expected. I’m not surprised that the incremental investors were less interested in financial planning than people who made the effort to opt into a plan. But notice that many of the people who would have opted in became less engaged when they were moved to a plan with automatic enrolment. The act of increasing convenience meant that both the incremental investors AND the “would-have-opted-in” investors paid less attention at the next point in the funnel (asset allocation).

So what happens when we force — rather than nudge — everyone to save? As you would expect, the savers are even more different, with even lower engagement in their retirement plans.

It’s Different Down Under

Australian law requires all residents to save 10% of their income every year. People can only access their savings upon retirement. The result? For many Australian citizens, their savings do not seem “real.” In a recent blog post, Bronte Capital’s John Hempton explains the problems with the mandatory saving plan:

Australians are forced to save almost ten percent of their salary into lock-box savings accounts that they cannot touch until retirement.

Twenty year olds are locking up tens of thousands of dollars that they cannot see, cannot touch and cannot benefit from for decades. They naturally enough become disengaged from this money.

This is real money though - and collectively it adds up to over a trillion dollars.

Bluntly - this is the biggest pool of disengaged money on the planet - with large amounts of financial assets held by people of middling to no financial sophistication.

Australia passed a law to ensure that everyone saved. That law succeeded in making everyone save. However, the law did NOT succeed in encouraging people to become more thoughtful about their savings.

Conversion Rate Optimization Bottlenecks

Imagine a four-step conversion funnel on a website. Maybe it looks something like this (with conversion rates):

Give us your zip code. (20% of website visitors provide a zip code).

Choose your “plan.” (60% of those who enter the zip code choose a plan).

Provide your email address. (30% of those who select the plan provide their email address).

Enter your credit card and make a purchase. (10% of those who provide an email address enter their credit card and make a purchase).

The total conversion of the people who visit your website is 20% x 60% x 30% x 10% = 0.36%. So you “monetize” 3.6 out of every 1000 visitors to your website.

In practical terms, your current 10-day funnel might look something like this:

10,000 website visitors

2000 zip codes collected

1200 plans selected

360 email addresses provided

36 credit cards charged

What happens when you run some A/B conversion rate optimization tests to improve the flow-through of various steps in the funnel?

To test ideas about achieving your ultimate goal — getting a higher percentage of visitors to enter their credit cards — it takes a lot of time to collect “significant data.” As a test, you might divide your total traffic (10,000) into two even groups; your expected baseline for ten days would be 18 sales in each group. Suppose you designed a new conversion flow that was 10% better than your current practice. Your control group would yield 18 sales, while your “test cell” would end up (in theory) with 18 + 10% = 19.8 sales. In practice, the statistical noise will make it impossible to validate the difference between the test and the control.

Depending on the magnitude of any changes, you will likely need to wait 3–4 MONTHS before learning whether your new idea is any better than your old idea.

Many (impatient) marketers realize that you can run a lot more tests at the top of the funnel than you can at the bottom of the funnel. As a common example, you might test your landing page to try and get more visitors to enter their zip code. Let’s imagine your new landing page could perform 10% better than your current one. Based on the above example, your control group would collect 1000 zip codes and your test group would collect 1000 + 10% = 1100 zip codes. Those results may or may not meet a formal significance test, but they could (roughly) confirm your new landing page’s effectiveness.

But — your test will ONLY confirm your new landing page’s effectiveness for collecting zip codes.

You still have no idea what will happen in the next step of your funnel. And you can’t just assume that all of your downstream metrics will remain the same. More likely, you will end up with something like this:

When you made entering the zip code easier (i.e., more convenient), the new incremental customers that came through the funnel were marginally different from the old ones. They were marginally less interested in your product, and they were more likely to drop out of the funnel at each additional step.

Some people in marketing call this phenomenon “the leaking bucket.” But the bucket will always be leaky. And the easier you make things at the top of the funnel, the less likely that people will make it all the way through to the bottom of the funnel.

The very act of growing your bucket makes the bucket leakier.

So What’s the Answer?

There ARE no easy answers. But there are two takeaway ideas:

Conversion Rate Optimization is a great way to test hypotheses (and much better than just going with “gut”). But exercise caution when looking at the initial test numbers, because the new people you get into your funnel will be less valuable than the old ones.

The best way to grow the bottom of the bucket is not necessarily by fixing the leaks. You can often achieve better results by just putting more customers in the top of the bucket.

Remember — the ideas in today’s essay are the “steel man arguments” AGAINST convenience. In general, increasing convenience is a very powerful tool. Yes, the new customers you bring in are less valuable than the old customers, but they are still (usually) incremental to your business. Guacamole is more popular today because it’s available at every major grocery store in easy-to-use squeeze bottles — even though that means most guacamole consumers are not as passionate about avocados as the superfans from a few decades ago. And convenience also increases sales from your most dedicated customers. The people who used to drive 10 miles out of their way for guacamole might be buying it twice as often now that it’s easy to pick up from their neighbourhood grocery store.

So don’t give up on convenience, just temper your expectations.

Keep it simple,

Edward

Edward Nevraumont is a Senior Advisor with Warburg Pincus. The former CMO of General Assembly and A Place for Mom, Edward previously worked at Expedia and McKinsey & Company. For more information, including details about his latest book, check out Marketing BS.