Last week, I wrote about the impact of cohort reporting. I struggled writing that newsletter — it was the hardest one I have written since launching Marketing BS last spring. In particular, I debated how much background context to provide the reader, before giving my own personal spin.

One week later, it seems like ALL the news is about COVID-19. As such, I’m continuing to wonder how much of the current situation should I explain to readers, and how much should I assume? I would love your feedback on this in particular; you can reply to this email or post a comment at the bottom of this post. I’m happy to answer any questions and I can also direct you to the best resources that I have relied on.

Today’s post is long, because I am trying to offer a comprehensive perspective that doesn’t just recycle all of the mainstream news articles.

Understanding what could happen with respect to the coronavirus is likely more important to most of you than understanding how marketing works. Things are changing so quickly that a weekly newsletter may not be the best place to stay up to date, but I will do my best.

Today I am going to write about the pros and cons of trying to duplicate the actions of successful organizations — both generally and in this massive pandemic experiment we are all a part of.

Getting Everyone on the Same Page

The most important coronavirus event last week was the March 16 publication of a paper by the Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team. This report had circulated among political leaders for some time before it was released publicly. The paper’s release motivated many governments to impose lockdown policies at approximately the same time, even though the outbreak’s penetration in different geographies varied significantly.

The Imperial College research team had access to sophisticated virus transfer models (things like, what would be the impact of closing schools? Or what if you shifted 25% of all white-collar employees to work from home? Or what if you restricted long distance trucking?). The researchers took their existing models and adjusted the parameters based on what we know about COVID-19. The results are not definitive proof of what will happen next, but the Imperial College report provided the best, most comprehensive attempt to understand the growth and impact of the disease. The conclusions were not pretty.

Jeremy C Young and Jason Crawford posted smart Twitter summaries of the Imperial College’s findings. If you prefer to read more extensive analysis, MIT Technology Review summarized the paper and discussed the ramifications. For a counter argument, The New York Times wrote about a (less influential) Columbia University study that reached vastly different conclusions (orders of magnitude lower).

Here some key findings from the Imperial College report:

Scenario #1. If we don’t do anything, ~80% of people will get the virus and 0.9% will die (disproportionately those over the age of 70, where 4-8% will die). In the US, this mortality rate would lead to ~2.2 million American deaths. For context, the TOTAL deaths last year in the country from heart disease, cancer, accidents (including motor vehicle), respiratory disease, stroke, Alzheimer’s, diabetes, flu, and suicide combined for ~1.4 million. Total US deaths from ALL causes was ~2.8 million. In simplest terms, COVID-19 could be responsible for almost doubling the number of deaths in the country — and all around the world

BUT… that mortality rate assumes we will have enough ventilators to treat the patients with a reasonable outlook for recovery. If we run out of ventilators, ICU space, and the personnel to oversee them (which we would in the “do nothing” scenario), the Imperial College projections climb higher, to ~4 million (including 8-15% of all people over the age of 70). Most deaths would occur within an approximate period of 3 months. If this happened globally, COVID-19 could eclipse — by more than 50% — the death toll from WWII.

Scenario #2. Mitigation. This strategy involves isolating anyone with symptoms and anyone living with those people, as well as “social isolation” for all people over 70 years old. This approach “flattens the curve” (to use the recent parlance), but not enough — the number of very sick people would STILL overcome the healthcare system. Approximately 2 million Americans would still die. In other words, mitigation might save half the possible deaths from the “too few ventilator” projections, but we would still face double the deaths in the country from 2019. (Once again, this situation would occur in a 3-month window.

Scenario #3. Suppression. This strategy is being attempted in Seattle: (1) shut down schools, restaurants, and public spaces; (2) most companies work from home; (3) social distancing of the entire population; and (4) isolate anyone with symptoms and quarantine family members. Suppression works. Deaths peak at “only” ~3000 people in early April.

BUT… As soon as you move from suppression back to mitigation, the outbreak starts over again — all you have done is delay WHEN the 3-month devastation takes place. The Imperial College suggests you might be able to open restrictions for a month at a time (followed by 2 months of lockdown), with a few thousand deaths per cycle.

The Fallout

Given the horrifying conclusions from the Imperial College, you can understand why the report prompted massive action by governments all over the world. Theoretically, for every day that a jurisdiction delays the implementation of full suppression strategies, there will be a rise in the total number of deaths.

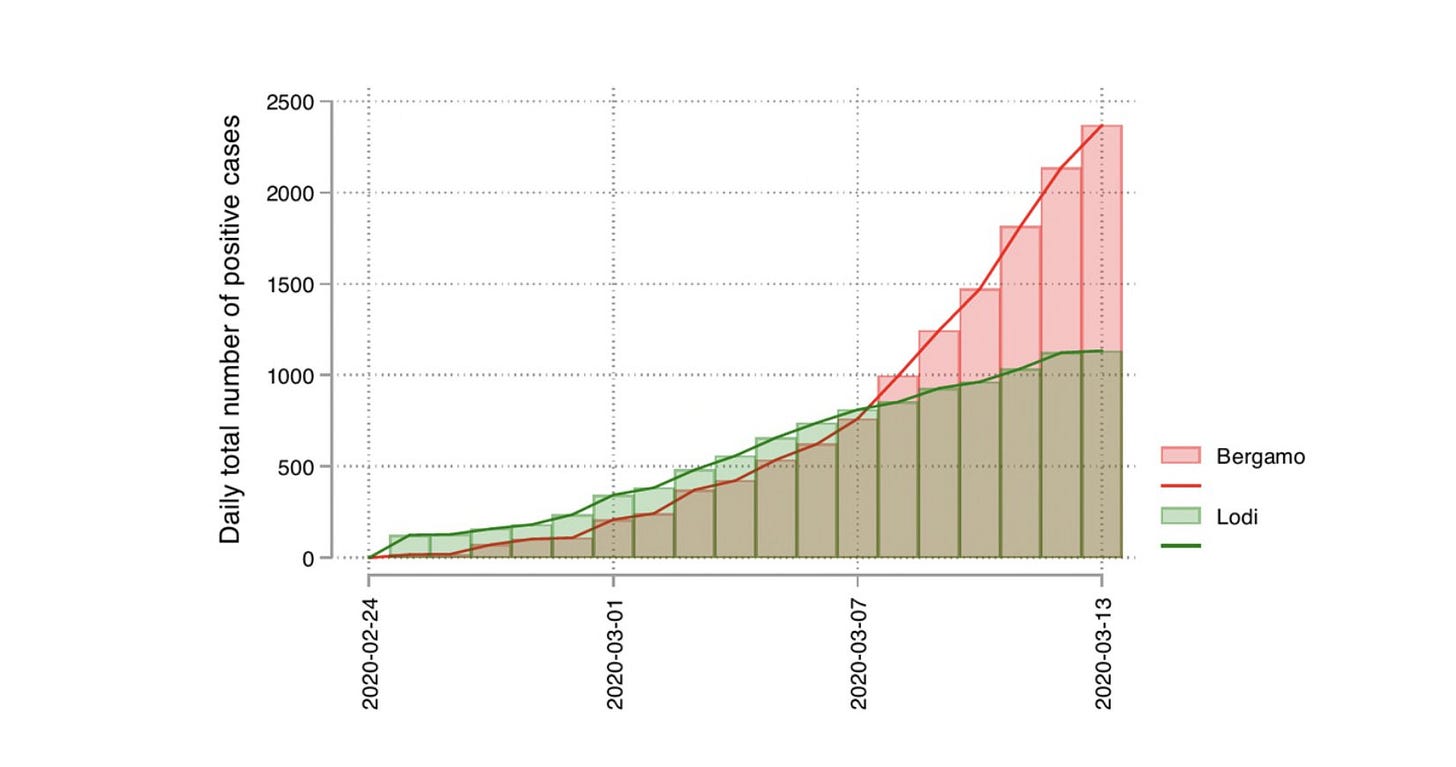

To illustrate the time-sensitive impact of suppression, take a look at two cities in northern Italy: Lodi and Bergamo. On February 23, Lodi imposed a lockdown; Bergamo waited until March 8 — a full 17 days — to take similar action.

As you can see in the above chart, the total number of diagnosed cases looks about the same for both cities until March 7 (~2 weeks after Lodi locked down). After that date, positive cases in Lodi continue to grow linearly, but Bergamo’s cases skyrocket exponentially (or, more accurately, on a “power curve”).

Outside of Italy, many regions implemented some level of suppression around March 14–15. Based on trajectories of impacted regions like Italy, we should expect cases in many countries to grow until (approximately) the end of March. Hospitalizations seem to surge ~1–2 weeks after infection, and most hospitalizations last a week or so. With that information in mind, we might see peaks in the healthcare system around the second or third week of April.

But then what? What’s the continuing strategy for dealing with COVID-19? A lockdown for the next 12–18 months until a vaccine is available?

Plus, what do we expect will happen to the economy during this time? In a brief period of time, lockdowns have inflicted massive damage to the economic standing of countries around the globe.

On March 17, Wagepoint — a Canadian payroll management company — sent an email to its clients, stating they could not handle the increased volume of requests for Records of Employment (a form used in Canada to determine eligibility for employment insurance benefits). For companies laying off employees, Wagepoint advised using self-serve tools provided by the government. From the email:

We write this with a heavy heart as we would love to help every business we can. However, we honestly believe that our suggested course of action is in the best interest of everyone involved.

In the US, Bloomberg looked at state unemployment claims, estimating that for the week of March 16, the total number might reach ~2 million. During the 2008 Great Recession, the single worst week for unemployment claims (last week of March 2009), saw “only” 665,000. If the 2020 pandemic follows a similar pattern to the 2008 recession, we could end up with 37 million unemployed — or 27% of the workforce. For comparison, unemployment during the Great Depression maxed out around 25%.

Could the economy really survive a lockdown of a year or more?

In a recent post on Marginal Revolution, Tyler Cowen makes the point that people will not stand for indefinite suppression.

...let’s say we start off being really strict with shutdowns, quarantines, and social distancing. Super-strict, everything closed. For how long can we tolerate the bankruptcies, the unemployment, and the cabin fever? At what point do the small businesspeople, one way or another, violate the orders and resume some form of commercial activity?

When a small business owner faces bankruptcy, at what point do they say, “Enough is enough.”? Will a restauranteur open their diner — even if it means the death rate for the country will double?

The UK attempted a plan to minimize COVID’s economic impact: allow young people to contract the infection (and hopefully develop immunity), but keep seniors as isolated as possible. The plan lasted all of three days and 10 deaths before the UK promptly switched course to the suppression strategies used by other countries. Tyler Cowen again:

Once the hospitals start looking like Lombardy, we don’t say “tough tiddlywinks, hail Jeremy Bentham!” Instead we crumble like the complacent softies you always knew we were. We institute quarantines and social distancing and shutdowns and end up with the worst of both worlds.

Clearly, we are in a real spot of trouble. Are we just going to yo-yo back and forth between suppression and openness, ending up with the worst of both worlds? What is the solution?

Chasing Best Practices

Ray Dalio is the founder and CEO of Bridgewater Associates, the world’s largest hedge fund. In 2017, Dalio’s book Principles hit #1 on the New York Times bestsellers list. Principles outlines the philosophy at the core of Bridgewater’s practices, something Dalio calls “radical transparency.” At Bridgewater, every conversation is recorded and analyzed. Employees rate each other after every encounter. Brutal honesty is expected. An old friend of mine worked at Bridgewater. He once told me that he “drank the Kool-Aid”; after four years, though, he felt the need to leave. Radical honesty, constant surveillance, and relentless judgement must be exhausting.

But the practice works for Bridgewater; it built a corporate culture that made them the largest hedge fund in the world, with over $160 billion under management.

So, if you were starting a hedge fund, should you read Principles and attempt to duplicate Dalio’s philosophies? If you are running a tech company, should you model yourself on Apple, Google, or Amazon (or all three)?

Many leaders take this approach. They read Fortune profiles and business biographies, trying to tease out the best practices of top companies. The logic seems reasonable: why not copy what works?

The problem? While Apple, Google, and Amazon are all extremely successful, they are also radically different.

Apple is focused on perfection. Even the feeling you get when you open the box (which you are going to throw away) has been carefully designed.

Google is focused on quick launches where they can test, iterate, and improve. This approach led to Gmail, Google Calendar, and Google Maps — all of which are much better now than when they launched. (On the flipside, this approach was also responsible for a social network with circles….).

Amazon builds low-cost platforms with small “pizza teams.” The company invests in as many fixed costs as possible, in order to drive down marginal costs as low as possible. Amazon finds a way to provide free delivery within 2 hours when you need a $5 coat hanger.

Copying “what works” from Apple, Google, AND Amazon isn’t really possible — many of those ideas are contradictory.

So, which company’s culture should you copy? I think that for most people that question is still misguided. When business leaders talk about copying corporate best practices, they usually end up cloning the obvious features.

New tech companies copied Google’s “20% time,” cool office spaces, and free lunches. Those were the obvious features covered in Wired Magazine features. But those things were not wholly responsible for Google’s success.

Companies achieve success based on the combination of hundreds of practices and philosophies. Costco and Walmart, for example, are both successful companies, but they treat their employees very differently. Costco focuses on long-term retention and development; Walmart focuses on keeping staff costs extremely low. Neither strategy is am intrinsically more effective business idea than the other.Both plans work because of how they fit within their respective companies’ overall system. If you replaced Walmart’s shelf-stocker compensation plan with Costco’s and left everything else the same, it would be a disaster for the retailer (and vice versa).

Too many business leaders look at the obvious features and say, “they are successful, so let’s do THAT.” By focusing on the obvious features, though, it’s easy to miss the myriad of other practices that made THAT work for THAT particular company.

Cloning Asia

Last week, California was the first state to order all of its residents to “shelter in place.” Multiple states have followed with progressively restrictive orders. Restaurants and retail have been closed. Events has been shut down. People have been told to stay at least 6 feet away from strangers.

These lockdowns resemble the actions taken by countries like China and Italy. Politicians and policymakers hope that by following the tactics in China — but earlier — they can avoid the likelihood of Wuhan-scale tragedy in the US. There is a major problem with this line of thinking, though: we are looking at Google and believing their success comes from the free lunches. We are cloning the obvious features of China’s response.

If a lockdown is the obvious thing China did, what are we missing by focusing on it (almost) exclusively?

On March 12, Rachel Maddow interviewed Donald McNeil, the science and health reporter for the New York Times (Here is the 6-minute video). McNeil explained that the lockdown in Wuhan wasn’t the END STATE; it was just the necessary FIRST STEP (excuse my manual transcription):

They had to do [the lockdown] in order to introduce the measures they were going to take to actually fight the epidemic. Testing, testing, testing. Find the virus. No matter where you go, your temperature is taken. If you go into any building, your temperature is taken... You get into a bus, your temperature is taken. You walk back to your apartment, your temperature is taken. [Maddow: “What if you show a fever?”] You are sent to a fever clinic… Your doctor’s office is dangerous… These are specific fever clinics they had since they battled SARS... Met by people in complete protective gear. Temperature is taken… Get a white cell count. They get a quick flu test — if you have one of those you can maybe go home. Then given a CT scan. CT scans in [America] take half an hour to an hour and are very expensive…. There they have portable CT scanners they and they push through [patients] at 200 per day... If you come up positive for that you do a PTR test… They do that onsite and they have it down to 4 hours… You sit and wait.... If they can’t get the scan results back that day, they go to a hotel apart from their family. 75% of transmission was in family clusters… They knew they had to stop that if they wanted to stop the disease… They even had dance classes… it helps clear their lungs if they have pneumonia, and the people who can’t get up, they might be the ones who are crashing… that was something that was medically smart going on.

The WHO report on China’s response plan noted the importance of fine-tuning strategies based on local contexts:

The strategy that underpinned this containment effort was initially a national approach that promoted universal temperature monitoring, masking, and hand washing. However, as the outbreak evolved, and knowledge was gained, a science and risk-based approach was taken to tailor implementation. Specific containment measures were adjusted to the provincial, county and even community context, the capacity of the setting, and the nature of novel coronavirus transmission there.

China started with a nation-wide campaign of monitoring, masking, and hand washing, but then evolved to focus on what was working at a more granular level. They understood that what worked in one part of China might not work in another part of China. In the US, we seem to have overlooked this important detail. What makes us think that a simplified version of China’s best practices will provide the ideal solution for America (or any other country)?

In China, the blueprint of “lockdown + surveillance + testing + isolation” was combined with herculean efforts to build new hospital facilities. Moreover, the country launched extensive propaganda campaigns. SupChina compiled a number of the slogans that were plastered all over the country. Despite the scary environment in which we all live these days, it is hard to read some of the expressions without laughing:

Stay at home to prevent infection, Turn your in-laws out if they come visit

Save pennies not wearing a mask, Spend a fortune getting treatment on your sickbed

No visits for the Chinese New Year this year, Those who come visit you are enemies. Don’t open the door for enemies

Visiting friends and relatives is a mutual slaughter, Partying is looking for death

A bite of wild animals today, See you in hell tomorrow

Everyone you encounter on the streets now is a wild ghost seeking to take your life

I’ll break your legs if you insist on going out, I’ll wreck your teeth if you challenge me

We laugh, because we appreciate that Chinese culture is different. That fact should be readily apparent to everyone. Still, we somehow think we can replicate the obvious parts of China’s plan, implement them into American society, and end up with the same successful results.

Strategies from Other Asian Nations

Taiwan implemented vastly different protocols than China. The Journal of American Medicine offers a concise account of the Taiwanese strategy:

For the past 5 weeks (January 20-February 24), the CECC has rapidly produced and implemented a list of at least 124 action items (eTable in the Supplement) including border control from the air and sea, case identification (using new data and technology), quarantine of suspicious cases, proactive case finding, resource allocation (assessing and managing capacity), reassurance and education of the public while fighting misinformation, negotiation with other countries and regions, formulation of policies toward schools and childcare, and relief to businesses.

For an idea of the strictness with which Taiwan imposed restrictions, check out the details surrounding the case of one “foreign national.” Due to recent travels in China, the individual was ordered to remain in self-quarantine from February 3–17. During this period, the person stepped out of his unit — for 6 minutes — to smoke in the building’s staircase. As a result, he was fined $333 (USD). The man’s name was kept anonymous, but that policy has already changed. On February 24, Taiwan's legislature passed a new law, permitting the “filming, photographing and disclosing the personal information of people who violate their home isolation or quarantine obligations.” For enforcement purposes, Taiwan was already tracking the locations of people’s phones; the threat of public shaming was just the next step.

And here’s another first-hand story from a student journalist in Taiwan:

Given Singapore’s links with China, the country faced the threat of a widespread coronavirus outbreak. And yet, the country avoided a massive penetration of the disease. On March 16, journalist Melissa Chen recently tweeted about the situation in Singapore:

I encourage you to check out her short (1:45) video of current life in Singapore.

Chen describes Singapore’s strategy:

- travel restrictions (they did this early)

- isolated infections

- aggressive contact-tracing procedures

- levied tough penalties for not following quarantines

- punished those who provided false info

- effective communication that struck right balance

- full transparency

And what they did NOT do:

- area-wide lockdowns

- edict to close businesses

- weld people shut in their apartments

- press to call government officials' actions racist

- punish whistleblowers

- care about "looking bad," thereby obscuring reality

Singapore kept their diagnosed cases to 243 and not a single death.

Japan was one of the first countries exposed to the virus. And yet, Japan neither implemented lockdowns, nor launch extensive training regimes. How did they pull that off?

Possibly, Japan’s success was a result of closing schools far earlier than other countries. Or perhaps elements of Japanese culture helped adopt widespread social distancing (people tend to live alone without roommates, greetings are met with bows instead of handshakes, etc.). Whatever the solution, they achieved a remarkable level of success, with just over 1000 cases and 33 deaths.

What about America?

So what about the US? Why are we in a state of highly varying treatments across the country — from “shelter in place” in California to spring breakers partying in Daytona? Part of the issue can be blamed on experience. Many Asian countries were hit hard by the 2003 SARS outbreak. Those governments still possess not only an institutional memory of pandemic horrors, but also healthcare infrastructure (even if mothballed) that can be dusted off and deployed.

Meanwhile in America, we have a few unique attributes that complicate a path to recovery:

Distrust of authority

America was founded in rebellion and, centuries later, its citizens still express (generally) more distrust for governments than citizens of most other countries. And that lack of trust goes both ways. For example, the CDC (rightfully) suspected that people might hoard face masks. Instead of transparently telling the American people that (1), yes, face masks CAN reduce your chance of infections, but (2) those supplies were desperately needed by the healthcare system, what did the CDC do? Issue a factually inaccurate a factually inaccurate statement claiming that masks were useless unless you were already sick. The CDC also misled the public about the existence of community spread and virus carriage on cardboard packages. Plus, they banned third-party testing. Is it any wonder that Americans are now so confused about the actual risks? Who should they trust?

Privacy Concerns

In multiple Marketing BS posts, I have argued that consumers do not care about privacy nearly as much as the media suggests. But the media and other “privileged classes” definitely push back against anything that looks like a privacy invasion (particularly when it comes from a technology company). The solutions implemented by China, Taiwan, Singapore, and South Korea all require vastly more surveillance and privacy invasion than anything that has ever been considered in America. The National Institute of Health has realized the need for partnering with companies like Palantir and Google, but the process has been slow. As you might expect, they are already receiving significant pushback.

Balaji Srinivasan was one of the first to raise the alarm about the virus. In a March 17 tweet, he tried to delicately explain that American concerns about privacy are preventing collaboration and research that might reduce the impact of the pandemic.

Legal Concerns

The US is a notoriously litigious society with “leading” patent protection rights. For an example of a story that is almost too unbelievable to be true, think back to the scandal of Theranos, the tech startup that claimed to have revolutionized the process and efficiency of blood tests. Theranos held hundreds of patents — without a single working product! Fortress Investments (a Softbank company) bought those “useless” Theranos patents. Fortress spun out a new shell company (“Labrador Diagnostics LLC”) with two of those patents; they are currently suing one of the companies working on a COVID-19 test, claiming the test would infringe on their patents.

Matt Parlmer, a freelance engineer, has been working on a N95 mask production project, but was told by the CDC that he cannot start manufacturing until his facility has been approved, a process that will take ~90 days.

Who should take the blame for the lack of testing in the US? The CDC certainly deserves criticism for stopping third parties from running any tests. The FDA should bear some blame, too. They forced the CDC to run tests twice for extra confirmation — even though that would half the total number of tests possible.

The end result is a society with massive aversion to risk. Most of the time, the fear of litigation just results in extra insurance payments (not to mention ubiquitous safety railings instead of the unrestricted vistas in other countries). But in this time of pandemic, America’s risk aversion has resulted in ventilator manufacturers running at lower capacity because they are uncertain they will be paid, and new entrants slowing down until they can get “legal support” to ensure they will be able to operate.

There has been discussions that in a worst-case scenario (where we may be soon), a patient could be kept alive using a “manual ventilator” like this one. These devices are sometimes used for short stints while transferring patients. Could they be put to use with a team of unemployed wait staff to keep people alive in the peak of the virus? Could you imagine a hospital in America agreeing to consider such a thing, even if the alternative was letting half their patients die? (A patient that does not get a machine because there were none available is one thing, but a patient that died because a ridiculously seeming treatment was provided is something far more likely to get someone in trouble).

Final Thoughts

Now what?

Without question, America’s patchwork of solutions is not working. Even if governments manage to prevent a catastrophic number of deaths within our borders, they are inflicting massive economic damage that will be long lasting. We need to find a way out.

I expect the solution will NOT be found by trying to clone another country’s methods, if only because American culture will rebel at many of the required solutions. I believe there are two paths to ending the COVID-19 threat:

we find within our society the humility to fundamentally change the way we operate, by accepting the need to duplicate another country’s full solution (and not a partial one)

we hope that researchers and policymakers will develop a uniquely American solution

I want to leave you with Balaji Srinivasan one last time:

Keep it simple — and stay safe,

Edward Nevraumont

If you enjoyed today’s newsletter, I encourage you to click the little heart button below the “Subscribe Now” box. Thanks!

Edward Nevraumont is a Senior Advisor with Warburg Pincus. The former CMO of General Assembly and A Place for Mom, Edward previously worked at Expedia and McKinsey & Company. For more information, including details about his latest book, check out Marketing BS.

Brilliant article Ed

Excellent piece. I appreciate the hard work and clear thinking.