Marketing BS: People don't care about your polls

Good morning everyone,

The outcome of the presidential election surprised many people — including the pollsters. But were the polls actually wrong? And if so, why were they wrong?

What can the election results teach us about surveys in general and market research in particular?

Due to the timeliness and significance of post-election analysis, I have shared today’s essay with both free and premium Marketing BS subscribers. (Learn more about subscribing to Marketing BS).

—Edward

Polling catastrophe

The day after the election, The Atlantic featured David Graham’s opinion piece about the “polling catastrophe.” (The article appeared after the initial election results were released, but long before final tallies for Pennsylvania, Georgia, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Arizona). Here is the core idea of Graham’s article:

Surveys badly missed the results, predicting an easy win for former Vice President Joe Biden, a Democratic pickup in the Senate, and gains for the party in the House. Instead, the presidential election is still too close to call, Republicans seem poised to hold the Senate, and the Democratic edge in the House is likely to shrink….

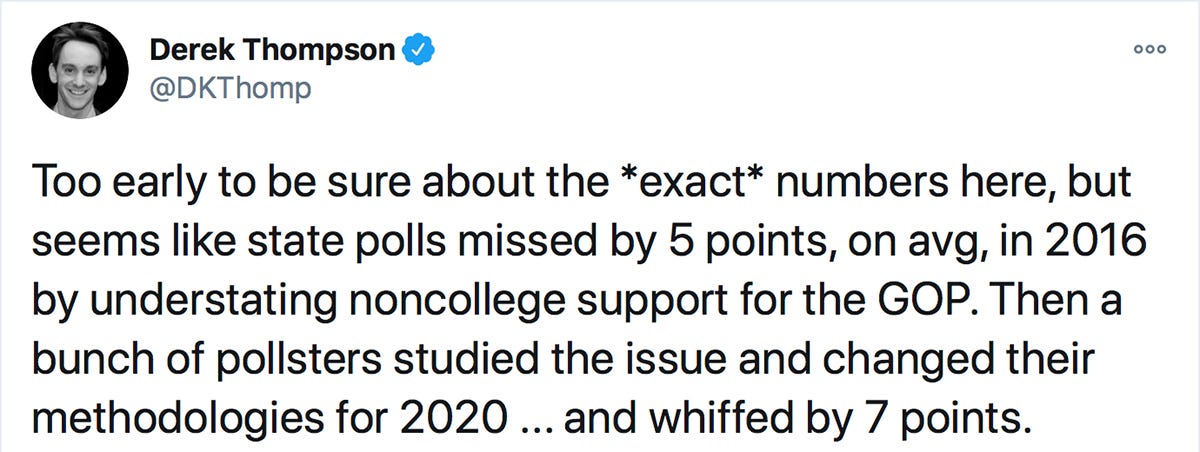

Derek Thompson, another writer at The Atlantic, connected the 2020 results to the infamous polling errors of 2016.

Back in early 2018, The American Association of Public Opinion Research published a comprehensive analysis of the 2016 polling misfires. Here are the highlights from their report:

1. Real change in vote preference during the final week or so of the campaign.

2. Adjusting for over-representation of college graduates was critical, but many polls did not do it.

3. Some Trump voters who participated in pre-election polls did not reveal themselves as Trump voters until after the election, and they outnumbered late-revealing Clinton voters.

4. Change in turnout between 2012 and 2016 is also a likely culprit.

The AAPOR’s list of explanations seemed logical at the time. But after ANOTHER round of polling misses, it is worth questioning the validity of their conclusions.

Let’s revisit the above four points in the context of the 2020 results:

Point 1: It SEEMS like there was no “last minute change in voter preference.”

Point 2: Pollsters claimed they definitely adjusted their methods to properly account for non-college graduates.

Point 4: Turnout was WAY UP (which pollsters believed would benefit Democrats).

We are left with Point 3: “Trump voters who did not reveal themselves” — aka “secret Trump voters.” This point feels like a reasonable explanation. If a liberal voter supported Donald Trump, they might be uncomfortable sharing that information with anyone, including pollsters.

But what about Susan Collins? The senior Senator for Maine, Collins is one of the most moderate Republicans in Congress. For months leading up to the election, her four-term run in the Senate seemed on the verge of ending. One of the last large-scale polls showed Collins trailing by a four-point margin, 43% to her challenger’s 47%. And yet, with 99% of the polls reporting, Collins won the election by almost 9 points (51.1% to 42.2%).

For the pollsters, the Collins outcome was a 13-point miss. The “shy Collins voter” explanation seems like a bit of a stretch.

So what is going on with polling? Why have the polls undercounted Republican support in two consecutive presidential elections?

Polling problems

In The Diff newsletter, Byrne Hobart argues that polling inaccuracies can be linked to a decrease in social trust.

For effective polling, two conditions must exist:

People speak with pollsters.

People share accurate answers with pollsters.

Without confidence in those two metrics, pollsters must compensate for the degrading quality of their input data. In particular, pollsters struggle to adjust for situations where those metrics vary at different rates for different groups. The challenges with polling variability were clearly present during this election cycle — pollsters tried to compensate for missing data by grouping “Latinos” together. The 2020 results underscored the fact that Latinos are not the homogeneous group that some believed (as illustrated by the Florida poll results).

Beyond people lying to pollsters, there is a problem of people lying to themselves.

The main question for presidential polls is straightforward: “Who will you vote for?” But to the extent that the question relates to policy questions or future intentions, the value of the answer degrades very quickly.

There are at least five known issues with drawing conclusions from survey responses:

Desirability bias. When you ask parents if they would pay more money for diapers that reduce rashes, they almost always say yes. And yet, most consumers will NOT buy the premium diapers in the store. The survey responses don’t really indicate parents’ price sensitivity for rash-resistant diapers; instead, people are answering the question of “Do you love your baby?” (with the obvious answer being “yes”). People do not want to look or feel bad when they complete surveys. We see a similar phenomenon in politics — the “Bradley Effect,” a term coined after the 1982 California gubernatorial election. (Pundits believe many voters — to avoid being seen as racist — told pollsters they would vote for the African-American candidate, even though they intended to vote for the white Republican candidate. Despite polling results showing Democratic candidate Tom Bradley with a large lead, he lost the election).

Word choice. Poll results depend on the specific language used for the survey. Consider these two questions: “Would you vote for a candidate who is pro-choice?” and “Would you not vote for a candidate who is pro-life?” The two questions ask (almost) the same idea, but they will yield different answers.

Innumeracy and ignorance. If you ask people “Should the rich pay more taxes?,” the majority of respondents will agree. But when you follow up by asking how much rich people should pay in taxes, the median answer is ~20% — which is a lot LESS than they currently pay.

Constraints. If you ask American citizens what they want from the government, they generally want MORE benefits: more healthcare (70% support Medicare for all), more education (60% support free college for all), and more roads (71% support significant increases in federal infrastructure spend). Most people want more of everything, except taxes (on themselves). For both families and governments, decisions are limited by constraints on money, time, and other resources. The hypothetical nature of opinion surveys makes it easy to ignore the ramifications and trade-offs.

Fragility. People change their minds all the time, even on the tiniest bit of new information. Ask people whether they support a market-based price for kidney donations, and they will generally say “no.” People will express concerns about the effects on the poor, the black market in kidney theft, etc. But spend two minutes explaining how the process actually works, and almost everyone flips to a “yes.” Which opinion do people actually believe? How will people respond if you ask them two days from now? Nobody knows.

Polling problems and market research

Policy and presidential polling receives more scrutiny than market research. More scrutiny usually results in a higher level of rigor. And if political polling can be so far off the mark, what does that say about the quality of in-house market research surveys?

In a 2013 lifestyle survey conducted by CNN, about 6% of people described themselves as vegetarians. But when those same people were asked if they had eaten meat in the last 24 hours, 60% said “yes.” In another example of peculiar polling results, 8.6% of American adults expressed BOTH of these opinions: “the world will not survive the next 100 years” AND “America will survive the next 100 years.” (Maybe they think Elon Musk will move America to Mars?).

Marketers spend countless hours each week thinking about their brand. Plus, many marketing professionals’ sense of self-worth revolves around their job, company, and industry.

As a result, marketers often struggle to internalize the fact that most customers don’t care that much about their brand. In fact, consumers just don’t think about your brand one way or the other. And when it comes to your market research surveys, customers certainly don’t spend much time or mental energy on your questions.

Market research involves two main parts: (1) asking people questions, and (2) drawing conclusions about what we know about those individuals, as well as the broader population from which they were drawn. Unfortunately, what people say they WILL DO — or even what people they say they HAVE DONE — regularly contradicts what people actually DO.

Economist (and Nobel laureate) Paul Krugman noted a number of bizarre inconsistencies from last week’s election:

Bottom line: what people SAY to pollsters is inconsistent with how they VOTE — just like what people SAY to market researchers is inconsistent with how they BUY.

Thankfully, people in the marketing world don’t need to rely exclusively on market research. Rory Sutherland, the Vice Chairman of Ogilvy & Mather Group, once said, “The job of science is to try and be right, the job of a business is to be less wrong than your competitors.” In many cases, reviewing market research is a better strategy than basing decisions on the highest-paid person in the room. But there’s also a value in balancing market research with experience, intuition, and anecdotes.

Steve Jobs famously quipped, “It’s really hard to design products by focus groups. A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.” Jobs held very strong opinions about the iPod (and later the iPhone); he refused the idea of surveying consumers to collect their opinions. Jobs was right on both counts and the rest, as they say, is history.

Although origin stories about the iPhone are commonly told, there’s far less attention paid to Jobs’s single-mindedness about iTunes and the App Store. When the iTunes store first launched in 2003, Jobs insisted that the platform should ONLY be available on Macs — no using iPods on Windows PCs. Apple executives disagreed. They believed that allowing PC-owners to connect an iPod would greatly expand the potential sales of the new music players.

How did Jobs respond to Apple execs? With another famous Jobs-ism: “Over my dead body.” But his team persisted. They commissioned market research study after market research study to persuade Jobs about the potential audience size for iPods. Jobs reluctantly conceded; iTunes was ported to PCs, dramatically expanding Apple’s global influence.

But Jobs did not learn his lesson. The same process repeated itself a few years later, with the launch of the App Store. Consistent with his desire to keep iTunes within the Mac ecosystem, Jobs wanted Apple to be the sole developer of iPhone apps. Once again, his team conducted market research studies that revealed the massive opportunity of allowing broader access. A herculean lobbying effort eventually wore down Jobs: “Do whatever the hell you want”. [1]

Now what?

David Graham, author of the “polling catastrophe” piece that kicked off this essay, is concerned about more than just the accuracy of polls. Graham articulates why the failure of polling could pose an existential threat:

The real catastrophe is that the failure of the polls leaves Americans with no reliable way to understand what we as a people think outside of elections—which in turn threatens our ability to make choices, or to cohere as a nation.

I have no comment about what Graham’s idea might mean for the future of our democracy and society. But from a marketing perspective, I fully recognize the dangers of inadequate polling — if we can’t accurately gauge what people think about certain topics, then how can we possibly use their feedback to guide our decisions?

Market research can make you feel better about understanding your customers, but that doesn’t mean you actually understand your customers any better than you did before.

For both the 2020 and 2016 presidential elections, the polls were off, but not by THAT much — 5 to 10 percentage points at most. That margin seems significant in a system where elections can be decided by two dozen voters in an Atlanta suburb. But in the business world, a deviation of 5–10% from the conclusions of a customer survey is pretty minor — certainly not enough to derail your presentation of a game-changing opportunity in front of an overconfident CEO.

The introduction of the Marketing BS podcast features a recording of Jeff Bezos’s famous quote: “The thing I have noticed is when the anecdotes and the data disagree, the anecdotes are usually right. There's something wrong with the way you are measuring it.”

Most of the time, the anecdotes and the data AGREE. Only in the rare moments of divergence do you need to think deeply. I concur with Bezos’s perspective that data is usually wrong in those situations. But I encourage you to also consider what we can learn from the Steve Jobs examples — when the data is STRONGLY pushing away from gut instinct, it CAN be time to let the data overrule the anecdotes (unless you have good theoretical reasons to support your instincts).

You can use market research to identify a broad generalized idea, but there are limits. As soon as you start reporting that a 1% change in your consumer sentiment requires some drastic action, you have gone too far.

Graham reaches similar conclusions:

...Without reliable sources of information about public opinion, the press, and by extension, the public, should perhaps employ a measure of humility about what we can and can’t know in politics.

Replace “the public” with “marketers,” and then swap “politics” with “business” — you have a clear path forward for how businesses should be thinking about market research.

Keep it simple,

Edward

[1] The stories about Steve Jobs were drawn from the excellent book, How the Internet Happened. Highly recommended. The audiobook “performance” is also compelling.

Edward Nevraumont is a Senior Advisor with Warburg Pincus. The former CMO of General Assembly and A Place for Mom, Edward previously worked at Expedia and McKinsey & Company. For more information, including details about his latest book, check out Marketing BS.