Marketing BS: Risks of Storytelling

Good morning,

Today’s essay looks at the power of stories — starting with the fascinating tale of Elizabeth Holmes.

For this week’s podcast interview, you can look forward to hearing the second part of Tom Seery’s story. Specifically, we chat about the tools Tom used to grow the RealSelf business into the largest site of its kind in the world.

—Edward

The Rise and Fall of Elizabeth Holmes

Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes will stand trial for fraud-related charges…eventually. A few weeks ago, the courts delayed the start of her trial until August 31, 2021. Holmes is pregnant, with a due date of mid-July — the same time when her trial was scheduled to begin (and that date was already postponed for COVID-related reasons from July 2020 to October 2020 to March 2021).

In 2004, Holmes dropped out of Stanford to focus on her tech startup, Theranos. The company worked to revolutionize diagnostic testing; Holmes claimed that Theranos’ microwave-sized machines could perform more than 250 tests — from just one finger-prick of blood. Her invention could change the world. Early detection of health issues would lead to better medical treatment and a higher quality of life.

Prestigious conferences invited her to speak and magazines featured Holmes on their covers. A March 2015 article in Inc. described Holmes in absolutely glowing terms:

She is no impostor. She was an entrepreneur before movies and television made it cool. She is substance where often there's only flash.

During the next decade, Theranos raised more than $700 million from investors, including Tim Draper, Rupert Murdoch, and the Walton family. Plus, Holmes assembled a board with an astonishing breadth of political luminaries: Henry Kissinger, James Mattis, George Shultz, and more. Fortune named Holmes the youngest and wealthiest self-made woman in history, based on the company’s estimated value of $9 billion.

In October 2015, the shining edifice came crashing down. The Wall Street Journal published a scathing exposé about Theranos. According to journalist John Carreyrou, Holmes was not just a Silicon Valley self-aggrandizer — she was a serial liar. The finger-prick method and portable testing machines did not work; the company secretly ran patient blood samples through commercially available lab equipment. Everything was being held together with lies on top of lies.

The net worth of Theranos — as well as Holmes — plummeted down to $0.

After the company had collapsed, the full extent of her deception was finally clear. In addition to SEC lawsuits for Theranos, Holmes herself was criminally charged with 11 counts related to wire fraud. If found guilty, she faces up to 20 years in prison and $2.75 million in fines.

The story of Holmes’ rise and fall is Shakespearean. She told compelling stories (her beloved uncle succumbed to cancer at a young age) and cultivated the persona of a visionary genius (she mirrored Steve Jobs’ black turtleneck wardrobe, rarely blinked during conversations, and intentionally lowered her voice). Holmes deftly charmed scores of important investors and advisors; they believed her grand tales about Theranos’ ability to disrupt medical technologies on a global scale.

Holmes’ obsession with storytelling and status ultimately led to her downfall. Even as Theranos was falling apart, she refused to admit there was no steak to match her sizzle.

Marketers love to tell stories — and with good reason. Humans are much, much better at remembering a narrative than a collection of facts. A number of experiments have proved this point, including this one:

In 1969 two Stanford professors, Gordon Bower and Michal Clark, set out to test the memorability of words embedded in stories versus a random list of words. Students were asked to memorise and recall 10 sets of unrelated words. The control group remembered the words in any order they wanted. For the story condition the students constructed a story that contained all the words, one story per set. When asked to recall the words the students that constructed stories were able to remember six to seven times as many words compared to the random set.

Good advertising must not only capture a viewer’s attention, but also tie that attention to the brand AND have the viewer remember the ad and the brand. Stories are one of the most powerful ways to accomplish that feat.

The Power of Stories

Back in 2009, writers Joshua Glenn and Rob Walker conducted an experiment they called “Significant Objects.” First, they purchased a variety of inexpensive items from thrift stores and garage sales (for an average price of $1.25). Next, they commissioned 100 professional writers to craft a backstory for each of the items. Finally, they posted the items on eBay, curious if the stories would increase the perceived value of the trinkets.

The result? On average, the items sold for 28x what Glenn and Walker had paid for them. Before quitting your job to start a thrift store arbitrage empire, you should note that the magnitude was small, they only invested $129 in the original purchases, and the ROI does not include the value of their time or the payments to the writers.

Importantly, prospective purchasers were aware that the stories were fictional. Here is how Glenn and Walker described the parameters for their experiment:

The s.o. [significant object] is pictured, but instead of a factual description the s.o.’s newly written fictional story is used. However, care is taken to avoid the impression that the story is a true one; the intent of the project is not to hoax eBay customers. (Doing so would void our test.) The author’s byline will appear with his or her story.

Although 28x sounds impressive, many buyers were probably comfortable “over-paying” not as a way to acquire the trinket, but for the chance to receive a one-of-a-kind, handwritten story from the writer. In reality, I expect the stories’ impact is more likely to be incrementality than a multiplier.

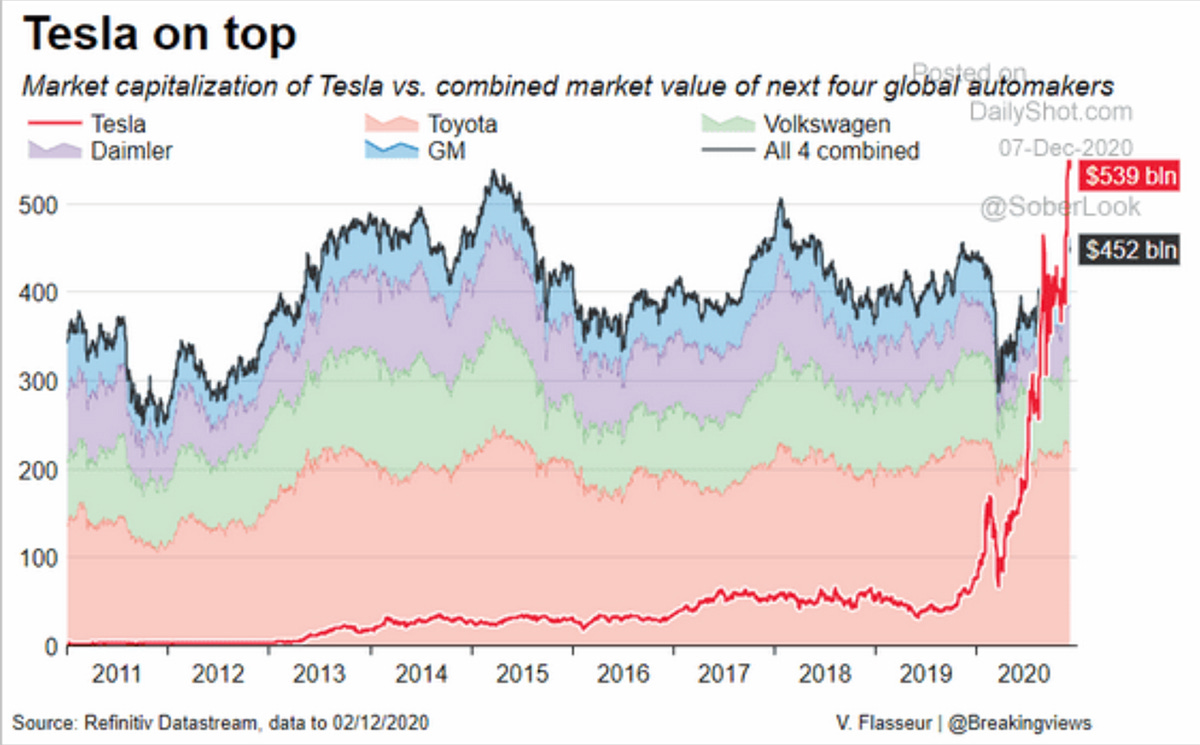

In Sapiens — the 2014 international bestseller — author Yuval Noah Harari argued that even fundamental concepts like “money” are based on shared delusions that are backed by stories. As one contemporary example, Tesla is now the most valuable car maker in the world — more valuable than the next four most valuable automotive companies COMBINED. Tesla’s value cannot be explained by their revenue or their EBITDA; their sky-high valuation is fundamentally a “story-based” one. Elon Musk is a master storyteller and showman, even if he can’t always deliver on (the timelines and scope of) his promises.

Check out this visualization of Tesla’s rise to the top:

With current interest rates close to zero (or sometimes below), the value of some companies is based more on their far future state than on their present-day fundamentals. Quite obviously, the far future is impossible to predict with precision; as such, values are derived from the quality of the stories being told instead of quantified financial projections.

So, ignoring the power of stories would be a bad decision. BUT — be aware that stories can backfire.

Uber was launched with the idea of disrupting the “black car” industry. Early venture investors pushed the founders to think one step further, by disrupting taxi services. Pretty quickly, Uber’s vision expanded to include the entirety of “transportation.” As they looked further and further into the future, they recognized an existential risk: what if self-driving cars would reshape the way people moved around a city, rendering Uber’s core product obsolete? And so, a mobile-first, tech-enabled taxi company started investing billions of dollars to develop autonomous vehicles. Last December, Uber divested their self-driving technology at a significant loss. What happened? Uber — and especially founding CEO Travis Kalanick — had become so focused on the story they were telling that they lost sight of the business they were building.

When Uber’s economics did not meet their ambitions, they took a hit. But unlike Theranos, they still HAD a real business to fall back on. Uber has since recovered and their current valuation of $108 billion is roughly double their worth from January 1, 2020.

As one final example, WeWork’s “storytelling gap” fell somewhere between Uber and Theranos. WeWork developed a reasonable model as a “short-term rent platform,” but that business was insignificant compared to the story that CEO Adam Neumann told his board, employees, and media outlets. The majority of equity holders were wiped out when WeWork’s valuation changed from a $50+ billion future fairy tale to a $3 billion real estate company.

Stories and Selections of Facts

What makes a good story?

Robert McKee is an iconic story consultant, famous for delivering workshops to Hollywood writers, executives, and more. In his seminal book Story, he articulates the essence of storytelling:

If you write a beat in which a character steps up to a door, knocks, and waits, and in reaction the door is politely opened to invite him in, and the director is foolish enough to shoot this, in all probability it will never see the light of the screen. Any editor worthy of the title would instantly scrap it, explaining to the director: ‘Jack, these are eight dead seconds. He knocks on the door and it’s actually opened for him? No, we’ll cut to the sofa. That’s the first real beat. Sorry you squandered fifty thousand dollars walking your star through a door, but it’s a pace killer and pointless.’ A ‘pointless pace killer’ is any scene in which reactions lack insight and imagination…You write so that when someone else reads your pages he will, beat by beat, gap by gap, live through the roller coaster of life that you lived through at your desk.

McKee’s point is clear: to create a good story, you should cut all the extraneous details.

Robert Henderson — a PhD candidate at Cambridge — extends this idea by noting that time washes away tedious details. In an issue of his “human nature”-focused newsletter, he wrote that historical stories, over time, become “compressed and simplified.”

I was in a museum with my girlfriend. We looked at exhibitions of inventions from the 17th and 18th centuries. Telescopes, power looms, old printing presses. We briefly thought, wow people back then were so smart. Then we realized, no, this museum is a monument for successful inventions. Museums do not display inventions that didn’t matter. Museums do not display the day-to-day failures of great inventors.

Both of the previous quotes highlight the idea that “selecting what to show” is a key element of telling a story. Note that McKee is (mostly) advising screenwriters who are free to invent and change details at will. In contrast, Henderson’s museum example refers to a situation where the stories are grounded in real-life events. Even if museums omit some historical information, they still display factual information about dates, locations, etc.

Marketers also “select what to show” — our job is to throw away 90% of the unnecessary details about a company and its products, so that we can focus our storytelling efforts on the most compelling 10%. But marketers must also ensure that the foundational details are truthful.

In telling the story of Theranos, Elizabeth Holmes behaved more like a Hollywood screenwriter than a marketer; she invented and changed details on a whim. The company’s entire valuation was based on the power of her storytelling. So much so, in fact, that when journalists and regulators started stripping away the fictitious parts of the Theranos story, there was nothing left (except, or course, an audience of betrayed investors and furious patients).

Keep it simple,

Edward

Edward Nevraumont is a Senior Advisor with Warburg Pincus. The former CMO of General Assembly and A Place for Mom, Edward previously worked at Expedia and McKinsey & Company. For more information, including details about his latest book, check out Marketing BS.